Author: Christopher Bryan

Thoughts for the Fourth Sunday in Advent, 2016.

This morning’s gospel passage is from the first chapter of Matthew’s gospel. If you know your Bible you’ll know it’s preceded by what Matthew calls “an account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah”—or, as the old KJV translated it, “the book of the generation of Jesus Christ” (Matt. 1:1-17). We don’t ever read it in church these days, because it seems unreadable. Look at it and I think you’ll see why! It traces Joseph’s family tree all the way back to Abraham, hundreds of years, and consists mostly of Matthew saying, “so-and-so was the father of so-and-so,” and so on through what he claims are forty two generations. Actually, when you count them it rather seems as though he’s only managed forty-one, which leads us to an old joke among seminarians: that Our Lord probably called Matthew to stop being a tax collector because Matthew couldn’t count! Being merely a disciple you didn’t need to be able to count!

What is really strange about this genealogy, however, is that although it is very carefully arranged with this monotonous list of fathers and sons—just as you’d expect in that patriarchal age—on four occasions it actually mentions someone’s mother: namely, Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and a woman whom Matthew calls “the wife of Uriah.” And what’s odd about these mentions is that they all involve something scandalous. Tamar deceived Judah to get him to have sex with her. Rahab was a prostitute. Ruth was a foreigner, a member of the despised Moabite race. And “the wife of Uriah” was Bathsheba, who was seduced into committing adultery by King David, who then tried to cover up his adultery by having her husband murdered. Not a pretty story!

And yet, Matthew claims—and of course, he has the whole of the Old Testament to back him up—through all these oddities and scandals and disgraces, God was working God’s purposes out.

At the end of Matthew’s genealogy the evangelist says, “Joseph was the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus, who is called the Christ,” or “the Messiah” (Matt. 1:16). And that brings him, and us, to the passage we heard for this morning’s gospel: “the birth of Jesus the Messiah,” in which Matthew proceeds to tell us the story of yet another scandalous oddity: to be precise, how Mary was found to be pregnant before she had had sexual relations with Joseph, to whom she was engaged.

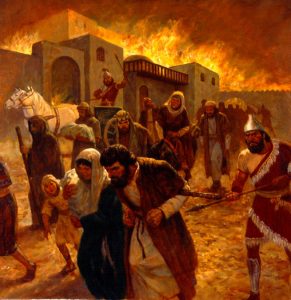

Joseph, not unnaturally, is taken aback. He is minded to “put her away,” as was his right, and some might even have argued his duty, under Jewish law. Mary could, if the matter had been pursued rigorously, have been stoned as an adulteress, since that was still technically the penalty for adultery. But then Joseph receives the message of an angel:“do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.”

rigorously, have been stoned as an adulteress, since that was still technically the penalty for adultery. But then Joseph receives the message of an angel:“do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.”

And this perhaps is the first thing to say about this morning’s gospel, the passage of Scripture with which we mark this final Sunday in Advent. For us, after two thousand years of Christian history and reflection, the nativity of Our Lord from the Blessed Virgin Mary is a beautiful story of maiden piety and faithfulness, rewarded by a grace that shall henceforth make Mary “blessed among women” (Luke 1:42). But who on earth would have believed such a story at the time? Would you? Would I? For us had we been there at the time it would surely have been a matter of shame and disgrace, and possibly of Mary’s being stoned to death for adultery.

And yet, Matthew tells us, through this particular scandal, as through all those earlier scandals, God was still working. Indeed, through this particular scandal God was working to bring about a supreme miracle, greater than creation itself: the miracle of Christmas, the miracle of the incarnation, wherein, as St John would put it later, “the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us” (John 1:14).

In other words, God is not afraid of scandals and oddities and upsetting of the normal order of things, and even works in and through them. God is not neat and tidy. Even when things seem to us to have gone utterly wrong, it will be a mistake to despair–just as it would have been a mistake to despair in those terrible hours on Calvary, on the first Good Friday, when Our Lord died as a condemned felon, and all surely seemed to be lost.

Two more things we are reminded of by today’s gospel.

First, the angel tells Joseph that he is to name the child whom Mary shall bear “Jesus”—that is, in Hebrew, “Yeshua,” which name means, “God saves” or “God delivers” or “God sets us free”. Sets us free from what? Surely from many things! We all have our sins, our failures, our addictions and weaknesses, all those things in the light of which we may well ask ourselves, how can we dare hope to be accepted by God Who is holy and pure and good? Will we not be struck down at once? The name of Jesus reminds us that God in Christ came to us, binding the divine glory to our sinfulness, precisely so that our sinfulness might thereby be bound to God’s glory: so that we might indeed be set free from what oppresses us. Jesus came for the forgiveness of our sins. Or again, as St. John would put it a few years later, “God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believes in him should not perish, but have everlasting life” (John 3:16).

Second, the angel says to Joseph that the young child shall be called “Immanuel, which means, God with us.” It is—and I seem to have been quoting this story rather a lot lately, but it is certainly not unsuitable for Advent—it is, as the writer to the Hebrews said, “a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God” (Heb. 10:31). But it is also, as famous British biblical scholar used to say, a good deal less fearful than the alternative. However fearful may be the prospect of God’s judgment, the prospect of a universe without judgment, and therefore of a universe without meaning and without hope is surely a good deal worse. Here then is the final Advent message, the final promise on this the last Sunday of Advent: that the God who comes to us in judgment, the dread king whom we must face upon the throne, has a human face, a face of compassion and mercy, the same compassion and mercy that he showed to sinners two thousand years ago: and it is the face of Jesus Christ. Jesus is God with us, our Immanuel. Even so, Matthew will record Christ’s promise in the final words of the gospel where, triumphant over death and the grave, Jesus tells his followers, “lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world” (Matt. 28:20).

Thoughts for the Third Sunday in Advent, 2016: the Sermon that was NOT preached at Epiphany, Sherwood because I thought the congregation looked too cold to be able to listen!

Gospel: Matthew 11:1-13

“Are you the one that is to come?” John the Baptist asks Jesus from prison. And so John reveals that even he—rough, gruff, uncompromising John the Baptist—has his moments of doubt and uncertainty. Some find that shocking. I don’t know why they should. It merely shows that like all the saints John the Baptist was human. What makes him a Saint—with a capital “S”—is of course that despite his doubts and uncertainty he hung in there.

You’ll notice our Lord doesn’t answer the Baptist’s question with arguments or proofs. He simply points to what is going on, to what he is doing, to his life, and to the life of those round him. “Go and tell John what you see and hear,” he says. Works of mercy, works of grace, works of deliverance, good news to the poor, the blind see, the deaf hear, the lame walk, life out of death: these are the signs of God’s presence, these are the marks of the Advent of the true Messiah—as the prophet Isaiah said they would be (Isa. 35:1-10). They were the marks of Jesus’ First Advent, and they will be the marks of his Second, his coming in glory.

And what of us? When the saints write or talk about their experience of God, they generally speak of it as gracious, sustaining, freeing and life giving. And they speak the truth as they have found it. When atheists write or talk they don’t, by definition, speak of their experience of God since they don’t believe God exists. They speak of their experience of religion, which they find graceless, oppressive, imprisoning and deathly. And I fear that they, too, often speak the truth, for only too often religion is all these things. That is why I think God must both love the church and hate it. God must love it because it hands on the stories and the traditions and says the prayers. God must hate it because it so often puts people off the very things it is handing on.

So what shall we do? One of Groucho Marx’s all time great wisecracks was, “I wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would have me as a member.” Combining this with our Lord’s answer to a troubled and confused John the Baptist, we have perhaps a clue as to the nature of the Christian life and witness to which we should strive. It is not that, when our faith is challenged or when someone else is in doubt, we are to produce arguments or slogans, still less threats of damnation! It is rather that we are to point to a life—the life of Christ that is graceful, sustaining, freeing, and life giving, and to a community that is imbued with that life.

But can the church be such a community? It can by God’s grace and sometimes even is. And we can do our little bit to help it become that by endeavoring ourselves live that life, perhaps taking as our daily commitment the attitude that St Francis’ prayer envisages:

O divine Master,

Grant that I may seek not so much

To be consoled, as to console,

To be understood, as to understand,

To be loved, as to love.[1]

So doing, we will be helping to form the character of a club that is indeed willing to have anyone as a member, and to which one might, nonetheless, still want to belong!

[1] For some reason Episcopalians are rather snooty about this beautiful prayer. I don’t know why. Perhaps it is because Saint Francis probably didn’t write it. Personally, I couldn’t care less who wrote it. It’s entirely Franciscan in spirit, and I’m quite sure Saint Francis approves of it. Let me, incidentally, commend it to you in its traditional form (which I quoted above) and not in the form given in our Book of Common Prayer. The traditional form is:

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me bring love.

Where there is injury, let me bring pardon.

Where there is discord, let me bring union.

Where there is doubt, let me bring faith.

Where there is error, let me bring truth.

Where there is despair, let me bring hope.

Where there is sadness, let me bring joy.

Where there is darkness, let me bring light.

O Divine Master,

grant that I may not so much seek

to be consoled as to console,

to be understood as to understand,

to be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive,

In pardoning that we are pardoned,

And in dying that we are born to eternal life.

Amen

Quite why the drafters of our BCP version felt free to omit “where there is error, let me bring truth” is a mystery to me. Although the omission may not be unconnected to another phenomenon that I notice lately—that so many in public life appear not to be overly concerned with “truth.” Anything goes, just so long as it makes an effective sound bite!

Thoughts for the Second Sunday in Advent, 2016. Text of a Sermon preached in All Saints’ Chapel, Sewanee, Tennessee, four days after the United States’ election

For the gospel: Matthew 3:1-12

“Repent,” said the Baptist, “for the kingdom of heaven has come near.’”

And it seems that they did. Many came to be baptized, “the people of Jerusalem and all Judea were going out to him, and all the region along the Jordan”—in other words, all the parts of the ancient kingdom of Israel—“and they were baptized by him in the river Jordan, confessing their sins.”

Among those who came were “many Pharisees and Sadducees.” This we should expect. The Pharisees don’t get a very good press in the New Testament, but they were in many ways Israel’s heroes. They’d stood courageously for her laws and traditions when others were willing to abandon them at the hands of foreign oppressors. Their almsgiving, fasting, and prayer life would put most of us here, certainly me, to shame. The Sadducees were, of course, Israel’s official ruling class: the high priest was invariably a Sadducee, and so were most of the Sanhedrin. They don’t get a very good press in either the New Testament or the rabbinic writings. Nevertheless, more conservative and limited in their views than the Pharisees though they were, they too in their own way upheld Israel’s national and religious traditions, and especially the glory of her Temple.

So it was only proper that such people should be part of a national repentance.

But then something shocking happens, something scarcely credible: John the Baptist turns on these national leaders!

“You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come?”

In God’s name what is he talking about? Why does he address the leaders of Israel in this way?

Fortunately for us, he answers these questions.

“Bear fruit worthy of repentance!” he says—and then specifies how: “Do not presume to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our father.’”

“We have Abraham as our father!”

Pride of nation, pride of race, pride of religion, “us-and-no-others”: these good men’s weaknesses are the flip side of their strengths. False pride was the very danger inherent in that ardent upholding of Israel’s Law that was their glory. It is, alas all too easy—and God knows we Christians have done it often enough—to slip from “we have been chosen by God to be God’s witness to the world”—which is what the prophet Isaiah told Israel (e.g. Isa. 49.6)—to “we have been chosen by God because we are great and mighty and special and wonderful and awfully important.”

Against which folly, if the Baptist had been in the mood, he could have quoted Moses: “It was not because you were more numerous than any other people that the Lord set his heart on you and chose you—for you were the fewest of all peoples. It was because the Lord loved you…!” (Deut. 7.7).

Or, as St Paul would later say to the Corinthians, “What do you have that you didn’t receive? And if you received it, why boast as if it were not a gift?” (1 Cor. 7.7)

As it is, the Baptist simply says with biting sarcasm, “I tell you, God can raise up from these stones children to Abraham!” There is no one in God’s eyes who is irreplaceable. There are no exceptional nations. There is only what God creates and chooses out of God’s free grace: and that, according to the Scriptures, is “all that God had made,” all that God named in the beginning and saw that it was “very good” (Gen. 1.31), the “all” that our Lord promises he will through his cross draw to himself (John 12.32).

Why does this issue matter to the evangelist? Why does he tell us about it? No doubt because he was writing fifteen or so years after the disastrous Jewish war against Rome of AD 70, the war that had brought about the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, the devastation of Israel, and untold suffering for the Jewish people, as well as the deaths of many foreigners caught up in it. Fifteen years meant time to reflect, and Matthew could now see that this meaningless and unnecessary war — see Martin Goodman’s magisterial Rome and Jerusalem[1] if you want the details — this “give me liberty or give me death” war which had been started, so the zealots claimed, in the name of God and God’s honour because the children of Abraham were too special to be part of any pagan empire — though God knows and the Scriptures tell us, they had in their history been part of several such empires, not always unhappily, and it was in fact, pagan, Persian money that had gone to build the second Jerusalem Temple – this revolutionary war was what the great teacher Yochanan ben Zakkai—known to Jews who know their history as “father of wisdom and the father of generations,” because he ensured the continuation of Jewish faith and hope and learning after Jerusalem fell—this war was what ben Zakkai said it was: “sinful and foolish.”[2]

So it is, as foreseeing the horror that will be caused by this xenophobia and national arrogance, that Matthew completes the Baptist’s words of warning: “Even now the axe is lying at the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.” As of course our Lord also foresaw when he was invited to admire the magnificence and beauty of the Temple. “You see these great buildings,” he said, “There shall not be left one stone upon another, that shall not be thrown down” (Mark 13:2).

What we have here then is an ancient story of folly and arrogance and xenophobia leading to chaos and destruction: a story of tragic dimensions, worthy a Homer or an Aeschylus or a Shakespeare. Is it then only an ancient story? No indeed. Greatness of any kind—moral, intellectual, political, military—always brings its danger: pride and arrogance.

Rudyard Kipling saw this quite well when he wrote his poem The Recessional, at the height of British imperial and world power:

God of our fathers, known of old,

Lord of our far-flung battle-line,

Beneath whose awful Hand we hold

Dominion over palm and pine—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

The tumult and the shouting dies;

The Captains and the Kings depart:

Still stands Thine ancient sacrifice,

An humble and a contrite heart.

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

And what happens when nations do forget?

Far-called, our navies melt away;

On dune and headland sinks the fire:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

And that of course has happened to at least one great nation, one world power, within the memory of some here.

One advantage I have in being able to remember World War II and the London Blitz is that I have vivid recollections, even as a five-year-old, of the transformation of a society that seemed ordinary and comfortable into one on which all Hell broke loose every night. And I saw from my childhood those pictures of refugees—my parents tried to shield me from them, but of course they could not—grimy black and white photographs of men and women who looked just like my mum and dad, with children clutching teddy bears just like mine, being machine-gunned by Messerschmitt 109s. So I have had some notion from the beginning of my life of how the fabric of civil society is fragile, much more fragile, I believe, than those of us who have always had the privilege of living our lives in such societies realize.

Britain did not collapse. Whether that was because, as Winston Churchill claimed, it was our finest hour, or whether less romantically, in the words of a Ministry of Defence poster that has now become iconic, it was merely because we kept calm and carried on, I don’t know. Perhaps it was a bit of each. But at any rate we muddled through, and emerged at the end at least in some measure recognizably what we had been at the beginning.

The society that did collapse, and that had already collapsed when World War II started, was of course Germany. Were the Germans a civilized nation? Of course they were—civilized and deeply Christian. Yet somehow, in the bitter aftermath of World War I there was a decay of rational hope and conversation, and permission given to the arrogant and narcissistic to rule. Those things broke the bonds of true community. I commend to you Milton Mayer’s They Thought They Were Free: The Germans 1933-45.[3] Mayer tells first hand of the gradual erosion of civil liberties that followed the election of Chancellor Hitler. He writes,

To live in this process is absolutely not to be able to notice it—please try to believe me—unless one has a much greater degree of political awareness, acuity, than most of us had ever had occasion to develop. Each step was so small, so inconsequential, so well explained or, on occasion, ‘regretted,’ that, unless one were detached from the whole process from the beginning, unless one understood what the whole thing was in principle, what all these ‘little measures’ that no ‘patriotic German’ could resent must some day lead to, one no more saw it developing from day to day than a farmer in his field sees the corn growing. One day it is over his head.

He concludes,

How is this to be avoided, among ordinary men, even highly educated ordinary men? Frankly, I do not know. I do not see, even now.

Personally, I think that Martin cannot see a sure way of avoiding this decay because there is none. “There was,” as the compilers of our first Book of Common Prayer pointed out, “never anything by the wit of man so well devised, or so sure established, which in the continuance of time hath not been corrupted.” In other words, it doesn’t matter how good something may be, there’s always someone who’ll come along and find a way to screw it up. And that surely applies as much to constitutions and systems of law as it does to liturgies.

But of course that does not mean that one gives up—either on devising liturgies or on trying to create rational and civil societies in which to live. God himself gave laws to Israel, and even, in time, a king. John the Baptist’s abrupt and arresting address to the political and religious leaders of his nation is as valuable to us as it might have been to them had they listened, because it reminds us of the seriousness of the decisions we make. The things we choose actually matter.

From the viewpoint of my poor wit—being, incidentally, myself an immigrant to this country—there are two things that seem to me especially important for us to choose, as we endeavour here and now to be a humane and civil society at this point in history.

First, as Albany puts it at the end of King Lear—a drama that shows us what happens to a society when humane and civil values are abandoned if ever one did—we must always try to, “Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.” What I mean is, we must be very fierce about what the ancient Greeks called parēssia[4]: the right of free citizens to speak their mind. This was the right that the founders of the United States—many of whom were of course classicists, consciously endeavouring to enshrine in their new republic what they saw as the best insights and aspirations of fourth century Athens and the ancient Roman Republic—this was the right that they placed first of all in their reflections on the constitution they had drawn up: freedom of opinion, freedom to argue, freedom to criticize the government, the right of the press and the media to ask awkward questions, even silly questions, the right to protest peaceably and the right openly to disagree with what our governments say or do. These are the marks of all free and open societies. Once a society gives up those, it is only a step to the knock on the door at two in the morning, the unexplained disappearances of dissidents and reformers, the bodies in unmarked graves, all that we associate with tyranny and dictatorship.

Second: Moses and the prophets repeatedly challenged Israel as to how it treated “the widows, the strangers”—that is, the aliens in its midst, the immigrants—“and the orphans.” Winston Churchill famously said, “I judge whether a country is or is not civilized by how it runs its prisons.” They are all, I think, making essentially the same point: that it is how a society treats its weakest and most vulnerable members—those who have no rights or have forfeited their rights or aren’t like us in some way—that tells us what kind of society it is. The Jewish American poet, Emma Lazarus, in her sonnet The New Colossus (which is slightly misquoted on the base of the statue of Liberty in New York Harbour) offered a vision of the United States as a nation gracious to the vulnerable:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me…!

Of course a society where people can say and think what they like and are different from each other in all sorts of ways is also a messy society, an untidy society, a disorderly society. And we love order. But beware of order without true law. Order is another of those good things that if made into a god becomes a demon. The Fascists and the Nazis brought order. They got the trains to run on time. And they did it while accustoming their people to mass murder. Actually, if you think about it, there is nothing more orderly than death. What could be more orderly than a row of coffins? But if you want life, think of a puppy: squirming, bouncing, tail-wagging, pooping, peeing, licking—totally messy. But how alive!

All that said, all that remembered, as Christians we do of course look beyond all these things to our final, Advent hope—to which the Baptist points us in this morning’s gospel. “I baptize you with water for repentance, but one who is more powerful than I is coming after me.” Thank God for that! Advent reminds us that at the end of all things we will fall into the hands of the living God, which is, as the writer to the Hebrews said, “a fearful thing”; but which is also, as famous British biblical scholar used to say, a good deal less fearful than the alternative.

Let us, nonetheless, be clear. God is not mocked. Our Advent hope can sustain us amid whatever perils and judgments we may bring upon ourselves in the present age, but it cannot deliver us from them. What will happen in history, we do not know. We never know. For the moment we can only, mutatis mutandis, take for our own the words of President Lincoln at a great crisis in this nation’s history: “fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray” that all may be well for this country and for the world over these coming years. But whatever happens, “as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgements of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’”

[1] Martin Goodman, Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations (London: Penguin, 2007).

[2] See e.g. Shaye J. D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1987) 32.

[3] Martin Mayer, They Thought They Were Free (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1955, 1966). For an excerpt, including the portion quoted above, go to http://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/511928.html.

[4] παρρησία: “outspokenness, frankness, freedom of speech, claimed by the Athenians as their privilege” (Liddell and Scott, Greek English Lexicon in loc.); cf. “a use of speech that conceals nothing and passes over nothing, outspokenness, frankness, plainness (Demosth. 6, 31)” (BDAG in loc.).

The First Sunday in Advent, 2016. A Sermon preached in All Saints’ Chapel, Sewanee, by Mother Julia Gatta

In the northern hemisphere, Advent falls during the darkest weeks of the year. And for us this year, the darkness of Advent is intensified by our post-election situation, a season of deep spiritual and moral darkness. Last week Chaplain Macfie noted the hundreds of reported incidents of racial, ethnic, and gender-based harassment that have exploded around the country in the aftermath of the election. Graduates of the School of Theology have sent us photos of their churches, whose walls or property have been desecrated by spray-painted swastikas and slogans such as “Heil Trump,” “Trump Nation,” “Whites Only,” and “Fag Church.” At least 200 churches have been similarly vandalized. Revolting and horrible as these things are, that is not the worst of it. The worst part of our post-election situation is that we are now on course to make this planet unlivable.

Addressing us in this grave situation are the lessons we hear on this First Sunday of Advent where Jesus speaks to us of his return—or advent—at the end of time. I find their ominous tone and apocalyptic imagery bracing and strangely comforting: the gospel finds us where we are. Faith doesn’t fool around; it’s about reality, including God’s surprising reality, and how we respond to it.

Today’s gospel begins with Jesus situated on the Mount of Olives, the very place where devout Jews expected the Messiah to come. There Jesus tells his disciples that even he does not know when he would return; the timing of his “second Advent” is a secret known only to the Father. In speaking of that momentous coming, Jesus drew upon the apocalyptic imagery of the Old Testament, as did St. Paul in his letters. In this scenario, our Lord’s triumphant return would be accompanied by cosmic catastrophe: the sun darkened, the moon failing to give light, stars falling from heaven. On earth, the birth pangs of the new age would be felt in the terror of earthquakes or the horrendous suffering of war. Most Episcopalians, along with many other mainline Christians, tend to find these passages in Scripture troubling, if not downright embarrassing. We are so repelled by hearing them interpreted with flat-footed literalism that we have rendered ourselves incapable of responding to their riveting poetry. We are so disturbed at seeing these Scriptures twisted into weapons to use against others or by ingenious attempts to put the end of the world on a timetable that we no longer hear their urgent message for ourselves. These passages are disturbing, it is true, but they are nonetheless crucial for a mature faith. And we especially need to hear them now.

Jesus frames his words about the end time in their largest imaginable social and environmental context: the story of the narrow survival of the human race and all other animal species. By alluding to the story of Noah and the Great Flood, Jesus drew from his religious tradition a tale of ecological catastrophe and of an entire people caught unawares. Noah’s contemporaries simply got on with their everyday lives as if things would just continue as they always had: “For as the days of Noah were, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. For as in those days before the flood they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day Noah entered the ark, and they knew nothing until the flood came and swept them all away, so too will be the coming of the Son of Man.” The days before the flood were just business as usual; but then, like a thief in the night, the flood came and the world they knew was destroyed.

Our situation is different, for unlike the populace in this primordial myth, we have been warned. Since the 1970s scientists have been telling us that the earth can no longer sustain the demands we have placed on her. Like Old Testament prophets they repeatedly urged us to change our ways before it was too late. We didn’t heed their warnings because we didn’t want to believe them, not because the data they brought forward was insufficient to substantiate their case. We wanted business as usual. In the Bible, such an attitude of willed blindness is called “hardness of heart.” “For in those days before the flood they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage . . . and they knew nothing until the flood came and swept them all away.”

One of the glories of the Anglican tradition, in my view, is its openness to truth from any and every quarter. St. Augustine once said that no matter where the Christian finds truth, the Christian knows that it is his Lord’s. This has been the characteristic Anglican approach as well, appreciative of both science and the liberal arts as ways of discovering the depth and breadth of God’s truth and wisdom. It makes a university like this, Episcopal in its foundation and character, a congenial place for seeking to integrate science, history, economics, literature, and the arts within a unified theological vision. It is also the mission of education to stretch our imaginations in all sorts of ways; to see that things may be true even if they seem remote and don’t immediately affect us.

Now we are facing some very disturbing truths. According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2016 is very likely to become the hottest year on record, surpassing 2015, the previous record-holder. In fact, of the hottest 17 years on record, 16 of them have occurred in this century. In September, you may have read that atmospheric concentration of CO2 permanently passed the 400 parts per million threshold—a number way ahead of where we thought we’d be some years back, when scientists were telling us that we could only avoid catastrophic climate change beneath the 350 ppm threshold. And that’s only what’s happening now. Because of a feed-back loop, climate change will continue to accelerate, even if we drastically curtail our emissions today. So the need for conversion of heart, for accepting limitation, for scaling back our greed and worship of convenience, and yes, for using our imaginations, has never been more urgent. God gave us this beautiful planet to tend and cherish. When we love and respect Mother Earth she, in turn, feeds and cares for us and all other creatures. Can you imagine a greater act of ingratitude towards our Creator or a greater crime against our children and grandchildren and the six billion people who share this earth with us than to wreak havoc with the natural cycles that have been in place for the last 12,000 years?

“You know what time it is,” writes St. Paul, “how it is now the moment for you to wake from sleep.” Rest is good when needed, but there is a spiritual sloth that is sheer escapism or despair. It is time to wake up, our lessons are telling us, in order to live fully alert to our situation—our personal situation and the world’s. Part of our awakening, Paul advises, consists in setting aside those habits that drug or dull our minds or dissipate our energies. In these dark days of Advent, many of us feel truly in the dark. We can acknowledge being bewildered, scarcely knowing what to do, without shame, for the journey of faith often navigates periods of intense darkness. Advent, like all the other liturgical seasons, simply underscores a dimension of the mystery of faith that is true year round. The watchword of Advent has always been vigilance: “Keep awake, therefore, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming.”

We are waiting for the Lord to come, for his Advent. Is there any doubt that we need a savior? And as we wait, what might be some signs of his coming? Today’s gospel speaks the apocalyptic language of cosmic catastrophe, but we do well to remember that the word “apocalypse,” contrary to popular notions, simply means “unveiling.” It refers to something becoming manifest that was previously hidden. That is why the final book of the Bible is sometimes called the “Apocalypse of St. John” and at other times the “Revelation of St. John.” In other words, apocalypse is about truth at last revealed. Having been polluted for so long by an avalanche of lies, even an “inconvenient truth” is welcome and cleansing. So when Christ comes, even now, he comes as truth. “I am the way, the truth, and the life,” he said.

Notice, too, how Christ comes to us in this Eucharist. He comes among us from the far side of death. He brings with him his own resurrected life. He irradiates our present with the future we share with him, filling us even now in these dark days with his life, and joy, and hope. He speaks to us through words of Scripture, and his holy presence fills humble things of earth: bread and wine, the products of soil combined with human labor and skill. And he transfigures them, transforms them. Bread and wine are brought to the table; we receive them back as Jesus our Lord. Even in the darkness, we have this light.

The day after the election, Dean Alexander charged all of us at the seminary to burrow into St. Paul’s 12th chapter of Romans. I pass on that sound advice to you. Some of Paul’s words have been lifelines for me. For instance, “Do not be conformed to this age, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect.” Or my personal favorite: “Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.”

Thoughts for Advent

It was more years ago than I care readily to admit, but I can still remember vividly the morning of my ordination to the diaconate. Thirty of us had been in silent retreat over the weekend, and now, released from silence, we were chattering noisily if nervously over breakfast. The archdeacon in charge of us, who appeared to be enjoying his moment of glory, got to his feet and cleared his throat.

“There are,” he said, “just a few last things.”

The bishop looked up.

“I think you’ll find there are four,” he said, and went back to his cornflakes. He was, I suspected, beginning to get just a little fed up with the archdeacon.

The interesting thing was that even in those palmy, far-off days when we like to think the church preached the faith and everything was simply divine, not every one got the joke. Even then it was a long time since the church had been expected to spend Advent talking about the classic four last things — death, judgment, heaven, and hell.

Of course we ought to have got the joke. We had spent most of the weekend in a chapel with Our Lord’s word from the Revelation to John carved above the altar in plain sight: Etiam venio cito ⎯“Surely I come quickly” (22:20). Shouldn’t that have put us in mind of death, judgment, heaven and hell?

Or perhaps the truth was we didn’t really believe it?

Actually, to be fair to us, we could have been forgiven if we’d wondered whether whoever put it there really believed it either. If they’d believed it, wouldn’t they have scratched it hastily onto the stone, or daubed it quickly with a bit of paint, or scribbled it onto newsprint? As it was, the letters were two feet high and several inches deep, carved in solid marble. Whatever the words might say, those letters were made to last. Whoever carved them clearly did not think that the Latin word cito meant “quickly” or even “soon.”

Or did they?

“Blessed is he who comes,” we say day by day at the Eucharist. And so we have been saying, give or take a decade or so, for two millennia. Of whom do we speak? Of the Christ, certainly, if we speak with those who spoke in the gospel. It is Christ who confronts us at the altar.

But then, where does Christ not confront us? From whom do I turn away, and I do not turn away from Christ? Benedictus qui venis! wrote Dante in the Purgatorio, “Blessed art thou that comest!”⎯and then spoke of the coming of Beatrice, through whom and in whom he saw the divine glory. That is what we must all say of whomever and whatever shows us the glory: “Blessed art thou that comest!”

Does a day go by in which, if I am honest, I must not admit that my judge has come to me, face to face, with mercy and justice? There is, to be sure, grief and meaninglessness in the world—and most of it put there by human ingenuity or cruelty. Let us never underestimate the horror we can cause—to our neighbours, to humankind, to the planet, if we are cruel enough or greedy enough or simply do not have enough imagination to understand what we are doing. “For I reckon,” St. Paul wrote, “that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory that shall be revealed in us” —but he did not say that the sufferings themselves were not real. African Americans survived slavery and lynching and Israel survived the holocaust: but that does not mean that those things were not horrific. Our Lord rose from the dead, but that does not mean that the crucifixion—his crucifixion and all crucifixion—was not horrific. Grace triumphs over evil, but that does not mean that evil is not evil. One reason why many of us (me included) find it hard to come to terms with Shakespeare’s King Lear, and why we need to, is that it presents to us without compromise a social order in which all human decency has been abandoned, and refuses to offer any possibility of reconciliation or hope in such a social order. What we choose is what we get. As Archbishop Rowan Williams has recently reminded us, “at some point, even the most confident faith (whether in humanity or in God) has to be honest about what is utterly unresolved in human experience, what cannot be made sense of (if making sense means showing why it’s a good thing really).”

But even when we have said all that, our faith and hope remain. Grace does triumph over evil, and destruction and death do not and cannot have the last word. Amid the horrors of racism and slavery there were those African-Americans who held fast to their hope in Jesus Christ. Amid the horrors of the holocaust there were those who died with the Shema upon their lips. Amid the horror of the crucifixion there was Our Lord’s prayer for those who crucified him. All of which is to say to say that when we have admitted that the evils that confront us in life—the evils that we create for each other—are real, we must also confess there is something else that confronts us if we will see it—even now, even in the midst of grief: there is the divine glory. “The world is charged with the grandeur of God,” as Gerard Manly Hopkins said, and today as in the beginning,

the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Or again, as Francis Thompson has it,

Not where the wheeling systems darken,

And our benumbed conceiving soars!—

The drift of pinions, would we hearken,

Beats at our own clay-shuttered doors.

The angels keep their ancient places;—

Turn but a stone, and start a wing!

’Tis ye, ’tis your estranged faces,

That miss the many-splendoured thing.

What, then, are we to do?

Our Lord tells us in our gospel passage that we must “watch”—or, as our rather feeble NRSV translation has it, “keep awake.” “Watch” (Greek, grēgorein; and in Jerome’s Latin, vigilare) is one of the most striking words of exhortation in our early texts: and was clearly taken by the first Christians with immense seriousness, as is manifest not least in those particularly Christian personal names that came to prominence in the early church, Gregory and Vigilantius. And what did they mean by “watch”? Not, of course, the foolishness of those Left Behind books, which exhort us to try to work out when the final coming of Christ will be—an activity that is, incidentally, explicitly forbidden to us by this morning’s text, as well as by other New Testament passages. No, “watching” for Christians is to consist of a concern for the rights and wellbeing of our fellow servants—which we surely now see must include humankind and the beasts and the good planet itself of which we have been made stewards (and it is required of stewards that they be found faithful). “Watching” means trying to be ready for the Master of the house whenever he comes, not presuming to ask when it will be.

Yet still we must not duck the final truth. As we declare in our creeds, the Master will come, and our watching will not last forever. What we remember especially on this first Sunday in Advent, or at any rate what we ought to remember, is that even the presence of Immanuel, God with us now, important thought it is, is not the end or the final promise. There is something more. That at least the Left Behind books got right, however much they may have got practically everything else wrong. In the end, whether we “watch” or not, whether we care or not, the marble will crumble — even those wonderful marble letters made to last for centuries will come to dust. The pretensions of nations, empires, planets, galaxies, and the universe itself (if it has any pretensions) will vanish.

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve . . .

We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

Or again—

On dune and headland sinks the fire:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

No one has said these things better than Shakespeare and Kipling in their different ways, though for those who want dominical authority our Lord said it too, and for those who want evidence the physicists will spell out more of the details.

And what then?

Then we shall fall into the hands of the living God, which is, as the writer to the Hebrews said, “a fearful thing,” but which is also, as a famous British biblical scholar used to say, a good deal less fearful than the alternative.

Then God will judge us.

Some call this the Great Assize, or Judgment, and such language reverts directly to the name by which we call this entire season, “Advent,” and the Latin and Greek words that lie behind it (adventus, parousia—words meaning “presence,” “arrival,” “visitation”). These terms were a part of the rhetoric of imperial Rome. They were used of an emperor’s official visitation to a city or province, when he would (among other things) do justice.

So what will God’s doing justice be like?

Of course the biblical language about this, and all language about it, is metaphorical. What other language could we use of that which we do not yet know? But on the basis of Christ’s first coming, I think we may safely say at least two things about his final coming to us.

God in Christ will judge us by the standard of divine love, and by that standard we shall stand condemned.

God in Christ will judge us by the standard of divine love, and through that love we shall be saved.

And what shall we have to offer in return?

We shall, please God, have our tears, which are the signs of contrition, and our prayers and our desire to be prayed for, which are the signs that we acknowledge our dependence upon God.

Through tears and prayers God can work in us, until at last we will be able to say with blessed Mary, “Behold the Lord’s handmaid, let it be to me according to your Word.”

When we can say that and mean it joyfully, as she did, then we shall be ready to raise our eyes to the throne, and to enter the joy of the Kingdom.

When we can say that, and mean it joyfully, then we shall be ready to respond to our Lord’s promise: “Surely I come quickly.”

“Amen. Even so, come, Lord Jesus.”

All Faithful Departed. A Sermon by Mother Julia Gatta

The Commemoration of All Faithful Departed,[1] which we celebrate today, has a somewhat different history and a different character from yesterday’s high festival. If the observance of an All Saints’ Day came about because of a deep Christian instinct to honor, first of all, the martyrs, and then later those exemplary Christians who were “the lights of the world in their generation,” the saints with a capital “S,” All Souls’ Day came into being because of another sort of Christian instinct: the urge to pray for the dead. Both feast days are grounded in the doctrine and the experience we have of the “communion of saints.” Our bonds to one another are not severed by death but are still, in fact, quite lively. And because we are still tied to one another in the living Christ, we believe that we can still help each other through prayer. In Christ, the veil separating this life from the next is quite permeable. And so it happened that by the late tenth century, a commemoration of all the faithful departed began to be observed first in monastic houses and then throughout the Western Church. It was set on November 2 as something of an extension of All Saints. But the spirit of this day is more somber. On All Souls’ Day, as it is popularly known, we recall the countless numbers of not especially heroic, but rather ordinary Christians who have lived before us, most of whose names are forgotten to all but God. Today we inevitably hold before God those dead who are especially dear to us, family members and friends. Some of these blessed souls were deeply faithful; others, like ourselves, were deeply flawed. Because God’s transforming grace reaches everywhere, including the realm of the dead, the life of the faithful departed is not one of static repose but a continual journey into the infinite depths of God, who purifies, reforms, heals, and irradiates us with his love. Our prayers for the dead articulate such a dynamic sense of grace. We began this liturgy by praying, “Grant to the faithful departed the unsearchable benefits of the passion of your Son.” In the burial office, we ask that they will increase in “knowledge and love” of God and “go from strength to strength in the life of perfect service” in God’s “heavenly kingdom.” There is movement, and our prayers lovingly connect us to all the faithful departed as they go forward ever more deeply into God’s light and life.

Continue reading “All Faithful Departed. A Sermon by Mother Julia Gatta”

Thoughts on Jeremiah after hearing Propers 23 and 24, Year C

The prophet Jeremiah isn’t generally associated with being particularly upbeat or cheerful. The prophetic book that bears his name is dominated by his predictions of doom and destruction for Israel and her king, and the other Biblical book associated with him—Lamentations—though not actually by him, is a series of poetic laments over that destruction after it’s happened. It’s surely not an accident that Jeremiah’s name has entered the English language in the word “jeremiad”—which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “a very long sad complaint or list of complaints.”

The prophet Jeremiah isn’t generally associated with being particularly upbeat or cheerful. The prophetic book that bears his name is dominated by his predictions of doom and destruction for Israel and her king, and the other Biblical book associated with him—Lamentations—though not actually by him, is a series of poetic laments over that destruction after it’s happened. It’s surely not an accident that Jeremiah’s name has entered the English language in the word “jeremiad”—which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “a very long sad complaint or list of complaints.”

Yet the readings from Jeremiah that we had last Sunday and this are actually rather hopeful and encouraging in tone, even though they date from a time when all Jeremiah’s gloomy prophecies have come to pass. Jerusalem has fallen to the armies of Nebuchadrezzar, Israel is now in thrall to the pagan empire of Babylon, and many of her citizens have been forcibly deported to Babylon. Continue reading “Thoughts on Jeremiah after hearing Propers 23 and 24, Year C”

Thoughts on the Story of the Unjust Steward

At the heart of his gospel Saint Luke presents us with a collection of four parables (Luke 15:1-16:8). They come in two pairs. We have a parable about a man (a shepherd with a lost sheep) matched with a parable about a woman (a housewife with a lost coin). Following those we have a parable about a father with two very difficult sons. That’s the parable that we usually call “the Prodigal Son,” although of course it’s as much about the elder brother who was not a prodigal as it is about the younger who was. And that parable is matched with the parable that the church, or at least those parts of the church that follow the Revised Common Lectionary, appoints to be read as a part of Proper 20 in Year C: a parable about a master with an unsatisfactory manager, or “steward” as the older translations generally have it.

Continue reading “Thoughts on the Story of the Unjust Steward”

Individualism

Our forebears before the Enlightenment had in general a deep sense of human solidarity. It was not that they were unaware of people as individuals, or that they did not care for them as such. One has only to read Euripides or Shakespeare to see that that was not the case. But in general they saw human existence as having little meaning except in relationship to others. The Stoic Epictetus is not untypical:

I will say that it is natural for the foot, for instance, to be clean. But if you consider it as someone’s foot, and not merely as a detached object, it will be fitting for it to walk in the dirt, and tread upon thorns, and sometimes even be cut off for the sake of the body as a whole. Otherwise it is no longer a foot. We should reason in some such manner concerning ourselves also. What are you? A man. If then, indeed, you consider yourself merely as a detached being, it is natural for you to live to old age and be rich and healthy. But if you consider yourself as a man, and as a part of the whole, it will be fitting, on account of that whole, that you should at one time be sick; at another, take a voyage and be exposed to danger; sometimes be in want; and possibly it may happen, die before your time. Why, then, are you displeased? Do you not know that, just as the foot in detachment is no longer a foot, so you in detachment are no longer a man? For what is a man? A part of a city, first, of that made up by gods and men; and next, of that to which you immediately belong, which is a miniature of the universal city. (Discourses 2.5.24, trans. Elizabeth Carter, revised Robin Hard, revised Christopher Bryan)

Firsts from a Couple of Small Islands*

For a small country (population about 4.5 million) New Zealand has a surprising number of “firsts.” As early as 1890 it was the first country in the world to establish an eight-hour working day for craftsmen and laborers on the principle, “eight hours for labour, eight hours for recreation, and eight hours for rest.”[1] In 1893 it became the first country in the world to give women the vote. The United Kingdom and the United States would not get round to it for another quarter of a century. In 1953 a New Zealander, Sir Edmund Hillary, and Tenzing Norgay, a Nepalese mountaineer, were the first climbers in the world to reach the summit of Mount Everest: the announcement of this achievement being a nice gift to young Queen Elizabeth II on her coronation day. New Zealand is the first country in the world to have three women in major positions of power simultaneously—the Prime Minister is Helen Clark, the Governor General is Dame Silvia Cartwright, and the Chief Justice, Sian Elias— hence New Zealand’s version of the “Keep Calm” tag: “Keep Calm and Let Girls Rule.” New Zealand is already a world leader in the use of renewable energy, and intends to be the first country in the world with 100% renewable energy: the goal is 2025, and may well be achieved. Continue reading “Firsts from a Couple of Small Islands*”

For a small country (population about 4.5 million) New Zealand has a surprising number of “firsts.” As early as 1890 it was the first country in the world to establish an eight-hour working day for craftsmen and laborers on the principle, “eight hours for labour, eight hours for recreation, and eight hours for rest.”[1] In 1893 it became the first country in the world to give women the vote. The United Kingdom and the United States would not get round to it for another quarter of a century. In 1953 a New Zealander, Sir Edmund Hillary, and Tenzing Norgay, a Nepalese mountaineer, were the first climbers in the world to reach the summit of Mount Everest: the announcement of this achievement being a nice gift to young Queen Elizabeth II on her coronation day. New Zealand is the first country in the world to have three women in major positions of power simultaneously—the Prime Minister is Helen Clark, the Governor General is Dame Silvia Cartwright, and the Chief Justice, Sian Elias— hence New Zealand’s version of the “Keep Calm” tag: “Keep Calm and Let Girls Rule.” New Zealand is already a world leader in the use of renewable energy, and intends to be the first country in the world with 100% renewable energy: the goal is 2025, and may well be achieved. Continue reading “Firsts from a Couple of Small Islands*”