Month: February 2018

Florence Li Tim-Oi: Text of a sermon preached by Fr Robert MacSwain in the Chapel of the Apostles, Sewanee, on 24th January 2017

In 1948, C. S. Lewis published an essay against the ordination of women titled, “Notes on the Way.” It was posthumously re-titled, “Priestesses in the Church?” with a question mark at the end, indicating Lewis’s dubiousness about the concept itself and whether it would ever actually happen in the Church of England. Since women were not ordained as priests in the C of E until 1994—almost 50 years later—Lewis’s worry was, shall we say, precocious. But it did happen, eventually, and of course women have been ordained in the Episcopal Church and other Anglican provinces since the 1970s.

Many of those who are opposed to the ordination of women appeal to specific biblical texts that speak against women teaching or holding authority over men, and I will come back to those concerns in a moment. But if you read Lewis’s essay you will find that while he mentions them he is less worried about exegetical matters as such. And he is certainly not worried about women’s capacity to do the work of ministry: preaching, pastoral care, administration, and so forth.

No, Lewis is primarily concerned about what he calls “the opaque element” in religious belief and practice. And by “opaque element” he means that in our religion which is not transparent to reason: the super-rational, mystical, divine revelation that makes the Church the Church and not just a voluntary human association. The opaque element is the given, the surd, the non-negotiable, regardless of how it might offend our natural human sensibilities. And for Lewis (at least when he wrote this essay) it was just axiomatic—beyond debate—that on the symbolic, imaginative, archetypal level women could not represent God. The masculine can represent the divine, but the feminine cannot. So while a woman priest could represent the people to God, simply in virtue of her gender she could not represent God to the people and therefore could not offer absolution or blessing or sacramental grace. To think otherwise was, for Lewis, to abandon Christianity for some other religion.

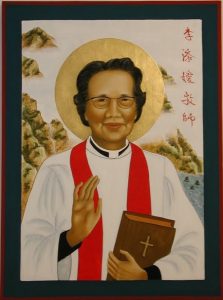

In her excellent chapter on gender in The Cambridge Companion to C. S. Lewis, Ann Loades suggests that Lewis’s essay was probably sparked by the post-war debate within the Anglican Communion regarding the priestly ordination of Florence Li Tim-Oi, whom we commemorate today. Li Tim-Oi, which means “much beloved daughter,” was born in Hong Kong in 1907. At her Anglican baptism some years later, she chose the name Florence after Florence Nightingale. After training as a teacher and working in a small island village, she went to mainland China to study theology, and was ordained as a deaconess in 1941.

When Hong Kong was occupied by Japan a few months later, Florence was already in the neutral territory of Macau as the only ordained person ministering to Anglicans. Since priests could no longer travel from Hong Kong to Macau, her bishop—the Englishman Ronald Hall—at first simply authorized her from afar to function as a priest, and then later, on January the 25th, 1944—the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul—they met in unoccupied territory and he formally ordained her as the first woman priest in the Anglican Communion.

After the war, however, when her ordination became general knowledge, controversy ensued. To avoid being a source of conflict, in 1947—the year before Lewis’s essay—Florence resigned her license to celebrate the Eucharist but retained her priestly orders. She continued to serve in the diocese, even as a rector, and Bishop Hall insisted that she still be called a priest—because…she was. However, after the Communist take-over of China in 1949, and the later Cultural Revolution in 1966 (during which she was forced into manual farm and factory work), Florence was not able to minister again publicly until 1971 when the Revolution ended and her priesthood was formally acknowledged in the diocese. She moved to Canada ten years later where she served first in the Diocese of Montreal and then in the Diocese of Toronto until she died on February 26, 1992.

Back to Ann Loades’s chapter on Lewis and gender: she astutely notes that more is going on beneath the surface of Lewis’s argument than he was perhaps aware. After rather crisply answering his specific concerns one by one, she then observes that the “primary difficulty here is that Lewis had his own ‘theology’ of gender which is perhaps more imaginative metaphysics than sober theology”. For example, while Loades does not mention Carl Jung, it seems that Lewis’s deep gender essentialism has more in common with Jungian archetypes such as anima and animus than it does with the Scriptural teaching that both men and women are made in the image of God and therefore both men and women do represent God, whether they want to or not and regardless of ordination. Indeed, I would argue that gender is not the issue: whether male or female, transgender, non-binary, or intersex, simply to be human is to represent God, to be God’s image in the world.

Universal human representation of the image of God is thus where all Christian thinking about gender should begin, before then moving to Paul’s revolutionary and still controversial statement in our reading from Galatians that within the Church all natural distinctions of race, class, and gender are overwhelmed in the waters of baptism—“for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” We’re still trying to figure out the full implications of that, but in light of Genesis 1 and Galatians 3, to say that women cannot represent God in virtue of their gender seems indefensible.

What then about those biblical passages mentioned earlier, in which women are forbidden to teach or hold authority over men? We don’t have time to go through them in detail, so let me simply make two comments here, one specific and one general. First, my specific comment is that instead of the sending of the seventy in Luke 10, a better gospel lesson for Florence Li Tim-Oi would Matthew 28, 1 through 10. For there we hear that the very first act of the resurrected Christ is to appear first to the women who came to minister to him even in death, and then directly commission them to go to the male disciples—who were still hiding in an attic somewhere—and to announce the resurrection to them: “Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me.” (Note the slight snark in that final comment: “there they will see me”—there, because they are not here.)

Likewise for Mary Magdalene in John, Chapter 20—hence her title even in Roman Catholicism as the “apostle to the apostles.” According to both Matthew and John, Christ first entrusts the message of his resurrection to women and commands them to share it with the men. In Mark 16 and Luke 24 it is angels rather than Christ himself who sends the women, but alas in Luke 24, verses 10 and 11 we read: “Now it was Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women who told this to the apostles. But these words seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them.” So, men not believing women that they have been sent by divine commission with the message of salvation has a long and un-distinguished history.

Second, my general comment about biblical texts forbidding women to teach or hold authority over men is that the Anglican approach to Scripture is not simple proof-texting. We don’t just pull verses out at random, but interpret them within the full testimony of Scripture and also in light of what else we know. As I have written elsewhere, “the authority of Scripture is not absolute and direct but rather relative to its historical/cultural context and mediated by critical interpretation.”

So, yes, those passages are indeed there—and so are texts such as Exodus 21:7 which regulates how a father sells his daughter into slavery. Now, I’m sure that last week during all those snow days those of you with children were flipping through your Bibles to find those texts, but I’m sorry: it doesn’t work like that. So when it comes to the ordination of women to the priesthood we look not only at the full testimony of Scripture, but also to everything we have learned about God and Christ and human nature in the last 2000 years. We also listen carefully to those many women who—like the women in the Gospel resurrection accounts—tell us that they have been entrusted by Christ with a mission to serve the Church.

In short, we listen to women like Florence Li Tim-Oi, “Much Beloved Daughter,” who, in the face of intense opposition from the Church and terrible persecution from the State, manifested remarkably Christ-like character: humility, faithfulness, obedience, and sacrificial love. Indeed, in so doing, she has enhanced and intensified, rather than diminished and diluted, our understanding of Christian priesthood. Rather than saying that she cannot, in virtue of her gender, represent God, we say, this is what representing God looks like. And so today we give thanks for Florence’s devoted witness to the resurrected life of Christ, and to all those faithful priests of the Church who, in sharing her gender, have followed not only in Christ’s path but also in hers. Amen.