Month: July 2017

“Prin”: A Reminiscence of the Reverend Canon Harold Wilson, D.D., Principal of Salisbury Theological College in England from 1965 to 1973.

It’s more or less forty years since the death of Canon Harold Wilson, who was one the two most important mentors in my life—the other being Fr John Crisp, about whom I have written and spoken elsewhere, and in whose memory stands the statue of Our Lady in the School of Theology Chapel of the University of the South. But I have never written anything about Harold Wilson. So here are some of my memories of this remarkable priest, whose influence for good on clergy training in the Church of England and through the C of E to the wider church has never, I believe, received the recognition that it deserves.

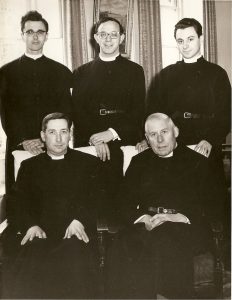

I first came to know Canon Harold Wilson—“Prin” as everyone called him—when he arrived in Salisbury to take over as Principal of Salisbury Theological College in the Autumn of 1965. I‘d been there for a year as tutor in New Testament under Canon Freddie Tindall, the previous principal. I dare say regime change took place with the usual testimonials, speechmaking and rituals of passage, but to tell you the truth, I remember very little about any of that.

The first thing about Harold’s presence that I do remember came a few days later. In those days “ordinands” (as seminarians are called in the Church of England) used to make much use of a very sensible little study of The Four Great Heresies by J. W. C. Wand. I was standing beside Harold in the corridor as one the students rushed past us saying, “I’ve lost my Wand. Has anyone seen my Wand?”

Harold turned and looked at me with that wonderful, lugubrious expression that I came to know so well over the next five years.

“Dear God,” he said in a soft West Riding accent, “I thought I’d come here to train priests, not magicians.”

Some days later he passed me again when I was standing in the same corridor looking at Karl Jaspers’s book, On Becoming Human.

“Oh,” he said peering at it, “are you thinking of trying?”

So one should surely begin by saying that Harold was, and always remained, a very funny man. Which was one of the many apparent contradictions about him, because he was also in many ways a very sad man, grieved by tragedy in his own life and the life of his family, and grieved by sorrows of the world to which he was acutely sensitive. It was surely typical of him that when World War II broke out in September 1939, Harold at once registered as a Conscientious Objector—on the ground that he did indeed conscientiously object to the whole notion of people settling their disputes by war—and at the same time volunteered for immediate call up to the army, on the ground that his personal scruples gave him no moral basis for not “doing his bit” (as we British used to put it) in the defence of his country, or for presuming to separate himself from the dangers and turmoil that the war was imposing on all young people of his age.

Harold would sometimes pretend to be arrogant and self-confident. I remember him sitting at a new electric typewriter (he loved new gadgets!) displaying its wonders, which included a gizmo so that you could correct mistakes.

“But I don’t use it,” he added.

“Why not?” I said.

“Because I never make any,” he replied, and then begun to shake with laughter, the overlong ash from his cigarette drifting down onto the keyboard.

And indeed, as I also came to know, he was really a humble man, often unsure of himself, willing to listen to suggestions from others. “Whenever you begin to say something to me and start off with the words, ‘With the greatest respect, sir,’” he said to me on one occasion, “I know I’m in trouble.”

Of course he transformed the School of Theology, introducing us to ideas and concepts such as the importance of feelings and relationships in decision making, and the workings and dynamics of groups, some of which are commonplace in theological education today, all of which were revolutionary then. He was blunt about the situation of the church, pointing out to us truths that many of us did not want to hear.

“The only numbers going up in the Church of England are burials,” he would say.

Yet he loved the church—her liturgy, her faith, and her hope—and only longed for the church to be what she can be when she is true to what she professes: faithful, vibrant, and holy.

“Let’s tart it up a bit,” he would say of a boring service—and did. At a time—the 1960s—when the church as a whole had scarcely begun even to think about liturgical reform and renewal, under Harold’s leadership we were soon using forms of worship in the college chapel not dissimilar from the Church of England’s present Rite B or the Episcopal Church’s Rite 1.

As well as being a priest and pastor, Harold was also (and by training) an artist. So the liturgy and its setting was also always beautiful. He saw to that and would allow nothing less. No kind of sloppiness was tolerated in the sanctuary or at the altar. Apropos which, on a visit to Salisbury Cathedral for Evening Prayer last month, I was delighted to see the priests wearing cassocks of a particularly interesting shade of green. That colour for cassocks is, I believe, unique to Salisbury, and I happen to know that it was Harold’s idea and inspiration. He felt that it was the right colour with which to respond to the cathedral’s architecture and light. I dare say he is as delighted to have made such a mark as that in Salisbury Cathedral as in any other of his achievements.

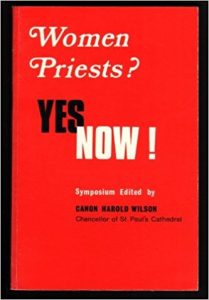

Harold saw clearly the rightness and necessity of ordaining those women whom God calls to the  priesthood—and he saw it at a time when 99% of us, including me, were still umm-ing and ah-ing about the whole question. “If you really believe Christ is present in the sacrament of the altar,” he’d say, “are you seriously asking me to believe He’s going to refuse to come because it’s a devout and sincere woman saying the prayers instead of a devout and sincere man?” He even edited a book about it–Women Priests? Yes, now! (Nutfield, Surrey: Denholm House Press, 1975). In his introduction he pointed out that “an injection of femininity would greatly enrich and enhance the priestly ministry and produce a valuable new dimension in the total life of the Church” (8). That has been precisely my experience in the years since the church began ordaining women to the priesthood, so that I am now sorry for those who cannot yet see it.

priesthood—and he saw it at a time when 99% of us, including me, were still umm-ing and ah-ing about the whole question. “If you really believe Christ is present in the sacrament of the altar,” he’d say, “are you seriously asking me to believe He’s going to refuse to come because it’s a devout and sincere woman saying the prayers instead of a devout and sincere man?” He even edited a book about it–Women Priests? Yes, now! (Nutfield, Surrey: Denholm House Press, 1975). In his introduction he pointed out that “an injection of femininity would greatly enrich and enhance the priestly ministry and produce a valuable new dimension in the total life of the Church” (8). That has been precisely my experience in the years since the church began ordaining women to the priesthood, so that I am now sorry for those who cannot yet see it.

Harold never claimed to be a theologian, but he believed deeply in Jesus as his Lord. Some people, of course, confuse being forward-looking with being apostate. One of the few times I remember seeing Harold actually get angry was when a student who had abandoned the faith said to him, “I learnt that from you.”

“You didn’t learn unbelief from me,” Harold replied crisply.

“A prophet,” said Our Lord, “is not without honour save in his own country and in his own house,” and this was certainly true of Harold. To this day, in my opinion, his pioneering work in theological education and the training of priests has not received the recognition it deserves within the Church of England. It was recognized almost at once, however, by a number of people in the United States. More precisely, my Sewanee friends will perhaps be interested to know that it was recognized by the University of the South, which in 1970 awarded him the degree of Doctor of Divinity, honoris causa. I was in the United States at the time, and so I was the one who got to telephone him—across the Atlantic, a big thing in those days!—to tell him the news.

“They want to know if you can come to Sewanee to receive your degree,” I told him, and named the day.

He was evidently delighted.

“I’ll be there if I have to swim,” he replied.

I think Harold’s supreme gift was his pastoral kindness. A student or a faculty member in trouble or sorrow would invariably receive an invitation to supper, the opportunity to talk, and a listening ear. My wife Wendy pointed out to me, shortly after she came to know him, that for her the greatest thing about him was the way in which, when he was talking to you, he was always paying attention to you—not thinking about where he wanted to be in a few minutes’ time, or someone else he’d rather talk to, but you, at this time, now. He was always fully present—in the moment.

It would be idle to pretend that Harold didn’t make mistakes, and especially toward the end of his time in Salisbury, when he became ill. There were things he did that he wished he had not done—and I know that, because he told me so. Alas, good Bishop Joseph Fison, who understood what Harold was trying to achieve in the Theological College and supported him, had died. Fison’s successor as Bishop of Salisbury seems to have lacked those qualities—so that at just the moment when Harold, who had given so much pastoral kindness to others, needed pastoral kindness himself, he received nothing, or less than nothing.

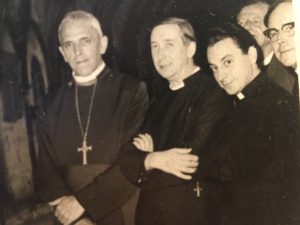

I was away from Salisbury in the United States during those last years, but then, some months after Harold had moved from Salisbury to London to be a Chancellor of Saint Paul’s Cathedral, I also returned to England. As a result I had the privilege of working with him again for a few years in London. I was diocesan officer for education and community, and Harold was the chairman of my board. In addition to that, Wendy and I had some pleasant evenings with him. I think that overall being at Saint Paul’s was a healing experience for him.

But then, after a year or so, his health failed completely—and to be sure, he was never a man who had taken proper care of himself physically. I’m glad I was with him in the hospital on the day of his death, within a few hours of it. The joyful thing about that is that I know he retained to the end his wit, his delight in life, and his faith and hope in his Lord.

Harold Wilson rests in peace, and he will rise in glory. Amen.