Month: May 2019

A Dreadful Tale: Text of a Sermon preached at St Stephen’s, Exeter on the Fifth Sunday of Easter, 2019

Gen 22.1-24; John 13.31-37 .

Our first reading this morning—about Abraham and his son Isaac—is surely one of the most dreadful stories ever told. I grant that as a family group Israel’s patriarchs and matriarchs do in any case seem to have been dysfunctional with a capital “D”, and a good many of the stories about them are pretty awful. It’s surely something of a tribute to ancient Israel’s modesty and good humour that she went on telling these tales about her founding family at all, unembroidered and un-cleaned-up as they are! No “father-I-cannot-tell-a-lie” nonsense here!

Even so, the story we heard this morning surely stands out. We’re told how Abraham is on the verge of killing his son with a meat cleaver[1] because God has told him to. No doubt, autres temps, autres mœurs. The fact remains, we live in a society where such an Abraham would be locked up, and the God who demanded his son’s death would be regarded as the product of a diseased mind. And I’m glad we do. All three Abrahamic faith communities—that’s to say we, and our Jewish and Muslim friends—have handed this story on in our different ways, and over the centuries all of us have evidently been troubled by the obvious moral difficulties that it raises. Rabbis, church fathers, and imams have at various times and in various ways sought to deal with or explain it—and none, perhaps, with entirely satisfactory results. That tricky tale is, however, what the church gives us to look at this morning, so let’s do it.

An ancient rabbinic suggestion is that God never really intended that Abraham would kill Isaac at all. God simply tested him to see how serious he was about his faith. No one I know of has stated this view better than Walter Brueggemann.

God tests to identify his people, to discern who is serious about faith and to know in whose lives he will be fully God… Faith is nothing other than trust in the power of the resurrection against every deathly circumstance. Abraham knows beyond understanding that God will find a way to bring life even in this scenario of death. That is the faith of Abraham.[2]

That is powerfully said, and apropos situations in which such faith has throughout history triumphantly manifested itself—the faith that sustained men and women in concentration camps, for example, or indeed the faith of Our Lord himself on the cross—it expresses an important truth.

The problem with it in the present context, however, is that Abraham is not in a concentration camp or on the cross. He is a powerful man, patriarch in a patriarchal society, responsible for the wellbeing of his household. Are we then to understand that he, the man in the position of power, is actually being called to create the very “scenario of death” into which God is then supposed to bring life? And how would he or anyone else distinguish such a call from the Satanic invitation to “trust” God’s promise by leaping from the pinnacle of the Temple, relying on the scripture that says, “On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone”?—to which the only truly faithful response was evidently Our Lord’s, “Do not put the Lord your God to the test” (Luke 4:11-12). The problem with this view, in short, is that for all the importance of what it asserts, apropos the story of Abraham and Isaac it leaves too many questions unanswered, nor does it really address their situation.

A suggestion for understanding the story along completely different lines is to suggest that “fear”—“Now I know that you fear God!”—isn’t at all what God really wanted from Abraham at that moment. This view argues that in the entire story of Abraham, his proneness to fear has actually been his weakness. It was fear that led to those embarrassing episodes where he lied to Pharaoh and then to Abimelech about Sarah (Gen. 12 and 20). Although in the matter of Hagar and Ishmael the narrator somewhat lets Abraham off the hook by telling of God’s word to him (“let it not seem evil in your eyes… the slave girl’s son, too, I will make a great nation” [20:12]) it is nonetheless fear of domestic strife rather than care to act justly that prompts Abraham in the first place even to consider casting out the slave girl and her son (who is, of course, his son too)—thereby exposing both to almost certain death. (It certainly isn’t because of anything Abraham does that Hagar and the child don’t die! Parallels in the biblical narrative between the narratives of Hagar and Ishmael on the one hand and Abraham and Isaac on the other have, of course, often been noted—down to the very words of the angel to each.[3] Arguably, God puts Abraham through precisely what Abraham himself put Hagar through: and surely that, too, is something to consider?)

Following on from all this, the suggestion is then that what God really wanted and even hoped for from Abraham following the command to kill Isaac was what Abraham had already shown himself capable of in other circumstances, namely an argument—an argument such as he’d offered earlier when God was about to wipe out Sodom (Gen 18:16-32): “Far be it from you to do such a thing, to slay the righteous with the wicked!”—argument such as Moses offered when God was about to wipe out Israel (Exod. 32.9-14) or the Syrophoenician woman offered when Jesus seemed reluctant to heal her daughter (Mark 7.25-30). To put it another way, St John says, “Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits, whether they are of God.” Perhaps God wanted Abraham to do a little thinking and testing.

Of all the attempts I’ve seen to get God off a moral hook, I confess this is the one I like best. My problem with it is that it doesn’t seem to square all that well with the narrative as we have it in Scripture: more precisely, with what the angel says to Abraham at the end about how his faithfulness will be rewarded, where it really does sound as though God is pleased with the way in which Abraham has acted (22.15-18).[4]

In view of all this uncertainty, it’s perhaps not surprizing that in the years leading up to the beginnings of Christianity some seem to have decided that the most interesting character in the story, the one you could best focus on and regard as its hero, was not actually Abraham at all, but the boy Isaac. It was, after all, Isaac’s life that was on the line, not Abraham’s.

Hence the title of the episode in much rabbinic treatment is “The Binding of Isaac”, reflecting this focus. The Targums—rabbinic translations of the Bible that add little bits of explanation and exegesis as they go along—emphasize how Isaac is willing to surrender his life if that is God’s will, and how the angels in heaven look on in wonder and admiration. Targum Neofiti has the angels say that from now on, whenever Israel sins and God is angry with his people, God will remember the righteousness of Isaac, and for Isaac’s sake will forgive them.[5]

What is perhaps especially interesting for us as Christians is that this way of understanding the story of Abraham and Isaac seems to have influenced the way the New Testament talks about Our Lord.

Think of St Mark’s gospel, and the word that the heavenly voice says to Jesus at his baptism, “You are my son, the beloved; with you I am well pleased” (1:11). In Mark’s Greek (given only the change of person required grammatically) those are exactly the words with which, in the Greek Bible, God charges Abraham to offer his son in sacrifice! The implication is surely that Jesus is God’s “Isaac”, who for the sake of the world will be willing to be bound upon the altar of the cross.

Again, remember in the Genesis account when they are on their way up the mountain Isaac asks his father, “Where is the lamb for a burnt offering?” Abraham answers, “God will see to a lamb for a burnt offering, my son.” And of course the ram with its horns caught in the thicket is the obvious fulfilment of that promise. But then St John’s gospel suggests a deeper and fuller fulfilment. John the Baptist points to Jesus and says, “Here is God’s lamb, which takes away the sins of the world!”—words, of course, that we continue to echo at the Eucharist when the bread is broken. “Lamb of God,” we say, “you take away the sins of the world. Have mercy on us… Have mercy on us… Grant us peace.” Jesus, again, is God’s Isaac, willing to be sacrificed for his people.

And this, of course, brings us to Jesus’ word to us in this morning’s gospel passage. On the eve of his passion and death, immediately after Judas has gone out to betray him, Our Lord says, “Now the Son of Man has been glorified, and God has been glorified in him”—which seems an odd way to speak of the fact that you’re being betrayed. He goes on to say, “God will also glorify [the Son of Man] in himself and will glorify him at once”—which seems, again, an odd way to describe the fact that you’re about to be crucified. But perhaps it is not so odd if it is Isaac who is here the model. Isaac’s glory was that he was willing to die for God’s people if that was what was necessary, and that is Jesus’ glory too.

So it was that at the end of the first Christian century Clement of Rome, writing to the Corinthians, would remind them how, “Isaac in confident knowledge of the future was gladly led as a sacrifice” (1 Clem. XXXI.3).[6]

We may still, of course, have a further question. We may wonder why at all, in the middle of Easter, when we’re celebrating Our Lord’s victory over death, the church has chosen for us our readings that actually turn us back to his death.

I’d say there are two reasons.

First, because by doing this we remind ourselves that Jesus did not, so to speak, “win” only by rising from the dead. Just as Isaac was triumphant in his willingness to give his life if that was what God required, so when Jesus was “obedient unto death, even the death of the cross” (Phil. 2:8)—indeed, when he was gracious to Judas who was about to betray him, when he was gracious to disciples who would flee as soon as he was arrested, when he continued praying for his enemies as he was being nailed to the cross, when he died commending himself into the hands of his heavenly Father—even in and especially in those moments, Jesus was already victor! That is why he says of his crucifixion, “Now is the Son of man glorified.” That is why his dying word in this gospel will be the triumphant, “Tetelestai! It is accomplished!” That is why in Mark’s gospel the pagan centurion, who has watched him die, cries out, “Truly this man was son of God!” (John 19.30; Mark 15.39).

Secondly, our turning back in the Easter season to Our Lord’s words at the Last Supper reminds us of something about ourselves and our own calling: namely, that our faith in Jesus, Easter faith, is not merely a conviction that certain things happened once upon a time two thousand or so years ago in a tomb in Palestine. It is faith that the living Christ has power to change my life now! For even as Our Lord speaks to us in the gospel of his love wherein he is, like Isaac, faithful even unto death, he at once goes on to say that we ourselves are capable of something that actually echoes that love: “I give you a new commandment,” he says. “Just as I have loved you, you also should love one another.”

“But Lord,” we cry, “to love as you love? We can’t possibly manage that!”

“But why not try?” he says. “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.”

And of course that’s true.

Why does anyone come to Christ or join the church? Is it because of our clever arguments or theology? Let me be clear—I love clever arguments and theology! But are they the reason why people join the church? I don’t think so. People join because they glimpse occasionally in some Christian or Christians a quality that draws them, a quality that we all desire, the quality that for want of a better word, in all its different forms and manifestations, we call “love”—linked to all the things that belong to love like compassion, kindness, good nature, a sense of humour, patience.

And by the same token I’d say people are put off the church by all that they see in us that is the opposite of love—pomposity, self-righteousness, coldness, nastiness towards each other.[7]

So—God help us!—in Jesus’ name let us try for

love, even as Jesus has loved us. Amen.

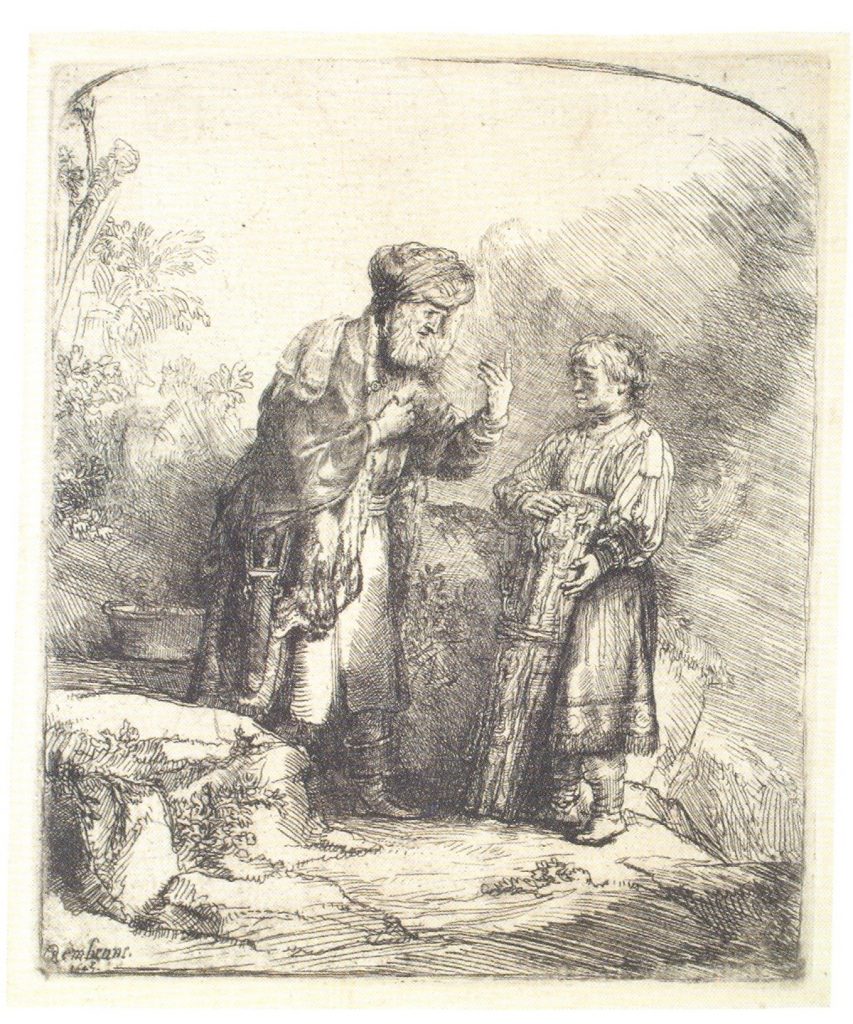

[1] Despite the more decorous “knife” of the NRSV and other translations (not to mention the elegant implement given him by Rembrandt), what we have here in the Hebrew (הַמַּאֲכֶלֶת) is not the usual biblical word for “knife”, and there is a case to be made for the suggestion that it is a term used for the butcher’s knife or cleaver: see e.g. Robert Alter, Genesis (New York and London: Norton, 1996) 105.

[2] Walter Brueggemann, Genesis (Atlanta: John Knox, 1982) 193

[3] E.g. Alter, Genesis, 106

[4] That these particular verses are perhaps a secondary addition to the narrative is beside the point. Our question as interpreters and preachers is how we are to understand the narrative as it stands in Holy Scripture now, not as it may have been at some earlier stage in its transmission. In any case 22.15-22 is certainly not an inappropriate addition, and there is no clear reason for supposing that the reviser, if there was one, understood the story other than as the original narrators intended it to be understood it: cf. Brueggemann, Genesis 185.

[5] E.g. 4 Macc. 13:12, 16::20; Pseudo-Philo, Biblical Antiquities 32:2-3; Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 1:132: see further James L. Kugel, Traditions of the Bible: A Guide to the Bible As It Was at the Start of the Common Era (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard, 1998) 304-305.

[6] Kirsopp Lake, transl. in The Apostolic Fathers, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann/Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1912) 60-61.

[7] “They’ll know we are Christians by our love,” goes a well-known and in my view rather dreary hymn written in the 1960s, presumably following Tertullian’s famous description of pagan reaction to Christians: “‘Vide,’ inquiunt, ‘ut invicem se diligent!’”—“Look,” they say, “how they love one another!” (Apologia 39.7). My own view is that Tertullian and the hymn-writer alike were indulging in wishful thinking. Alas, my own experience has been that non-Christians are as likely to be disgusted by our treatment of each other as they are to be attracted by the love that we claim to live by, and I see not the slightest reason to believe things were any better in Tertullian’s day.