Month: November 2017

Thoughts on Joshua and The Promised Land: text of a sermon preached at the Convent of St Mary, Sewanee, on Sunday 12th November 2017

For the Old Testament Reading: Joshua 4:1-3a, 14-25.

I’d like to spend a few minutes with you this morning looking at our Old Testament lesson. It’s a dramatic and memorable scene—even somewhat iconic. It begins with Joshua gathering together the elders, heads, judges and officers of Israel—all the movers and shakers, so to speak—and reminding them of what God has done for them. He does this at some length, and the compilers of our Lectionary, perhaps fearing our attention span is less than the Israelites’ (as indeed it probably is) have omitted quite a lot of it—ten and a half verses, to be exact—as you’ll notice if you check the story in your Bibles after Mass. Anyway, Joshua reminds them how God has delivered them from bondage and given into their hand the Promised Land, the land of the Amorites and six other nations.

“So,” he says at the end of it all, “worship the Lord, and serve him! Put away the gods of your ancestors!… choose this day whom you will serve! As for me and my house, we will serve the LORD.”

It is stirring stuff. The chap who used to come and do my plumbing even had those last words painted on the side of his van.

But wait a minute!

“Choose this day whom you will serve… Put away the gods of your ancestors” ?

Now that’s a bit odd, isn’t it? Can it really be that after all God has done for this people they still have their old gods with them? Apparently, it can. Still, they do seem to have got the right idea now: “Far be it from us that we should forsake the Lord to serve other gods!” they say. “We will serve the Lord, for he is our God.”

Joshua, however, doesn’t seem very impressed. “You can’t serve the Lord!” he says.

Why?

“Because the Lord is a holy God, a jealous God” – el qana in Hebrew, which means “a passionate God, a lover who will brook no rival.” “If you forsake the Lord,” Joshua continues, “and serve strange gods, then the Lord will turn and do you evil, and consume you!”

Perhaps Joshua is relying on counter-suggestibility? If so, it works, for the people now insist that they’ll be faithful.

“No, we will serve the Lord.”

Even then Joshua’s response isn’t exactly dripping with enthusiasm.

“You are witnesses against yourselves,” he says, “that you have chosen the Lord, to serve him.”

You are witnesses against yourselves! Joshua still seems virtually to assume that they’re going to fail. And they for their part seem to accept it, for their reply, “We are witnesses,” is terse and ambiguous. Actually it’s even more terse and ambiguous in Hebrew than it is in our English Bibles, for it consists of a single word. It’s as if they just nod their heads and say resignedly: “Edim – witnesses.”

Still, it seems to be enough. Joshua again says they must put away their foreign gods and serve the Lord, the people answer that they will serve and obey the Lord, Joshua makes a covenant with them, and the scene ends happily.

Or does it? Even then it isn’t without ambiguity. If you were listening carefully to the reading you may have noticed that though the people say they’ll accept Joshua’s second demand and serve the LORD, they don’t actually say they’ll accept the first, and put away the foreign gods. Nor does the narrative say that they did.

Now we might argue that their putting away foreign gods was implicit in their pledge to serve the Lord and in Joshua’s making a covenant with them. Yes, we might. But then, what’s implicit is only implicit. It has to be inferred. And isn’t it strange that the narrator should have left the resolution of this key issue to be inferred? That the possibility should be left open that Israel might still turn to some God other than the LORD who’d redeemed her from Egypt? That she might still serve other gods?

But that’s not the only thing that’s strange about this passage. I have quite a different problem with it, and it’s this: what about those Amorites?

I ran over that part of the story quickly just now, just as our lectionary does by leaving most of it out – but it’s in the Bible all right. Joshua reminds the Israelites how God brought them out of Egypt where they were being oppressed by the Egyptians, and led them into the Promised Land so that… so that… so that what? So that they could then oppress the Amorites! And indeed oppress them rather worse than the Egyptians had oppressed them—exterminate them, to be exact, and then live in their houses and use their vineyards. What an irony is here!

I read somewhere some years ago – to my irritation I can’t remember where – about someone visiting an archaeological museum where there were lots of things on display that had belonged to the ancient Amorites – pretty combs that girls probably used for combing their hair, and children’s toys. I wonder what they were like? Who were those girls who used those combs, and the children who played with those toys? Were the children sometimes affectionate and sometimes horrid – like most of us? Were the girls sometimes nice and sometimes nasty – like most of us?

But then, it really doesn’t matter, does it? For whatever they were like, the message to the people of God is clear: “you must utterly destroy them. Make no covenant with them and show them no mercy.” That’s what Moses had commanded Israel apropos the Amorites and those six other nations way back in the Book of Deuteronomy (7:2). So as for Joshua this morning, he was just obeying orders. Who cares what the Amorites were like?

Now even granted the Scriptures’ premise, that Israel is the chosen of God – which, indeed, I do grant heartily – still this sounds horrific. Israel the chosen is to be a source of utter destruction to the nations round her. Is this then the good news of God? Is this what Israel, and later also the Church, is to teach the world about God’s justice and mercy?

My first move, since I’m one of those pesky academics, is naturally to point out that this is theological fiction, designed to show the strength and depth of the Lord’s commitment to Israel. There were never really seven such nations as Deuteronomy names existing at one time for Israel to exterminate, and Israel didn’t really behave as badly as Moses seems to have said she should.

Well, maybe so. But does that solve the problem? Actually, it does not. In fact I think it makes it worse. After all, if this were simply history, one might reasonably say, “Well that was then but this is now.” But if this is theological fiction, then it’s a sort of symbol, a myth, if you will, of God’s dealing with God’s chosen. And the trouble with symbols is that they are transferable. You have only to decide that in the present situation you are God’s chosen and hey presto! – You can be perfectly clear and comfortable with knowing that God allows you behave toward people who aren’t like you or don’t have the same faith as you or don’t think like you or even happen to live in a country that you want to live in, in ways that in any other context you’d call cruel, dishonourable, and disgraceful. Ethnic cleansing, slaughter of non-combatants, murdering their children—what’s the problem? Jon D. Levenson, a Jewish biblical scholar whom I greatly admire, has suggested there’s a parallel between the Jews’ rapacious negation of the nations who had preceded them and the way in which Christians later rapaciously superseded the Jews.[1] Alas, I think Levenson is right. And throughout the next two thousand or so years we can see this theological fiction in one version or another being taken to provide biblical warrant, directly or indirectly, for all sorts of abominable nonsense:

Christian anti-semitism,

the burning of heretics,

the Christian rape of lands from their previous inhabitants (including, of course, those lands that we now call “the United States”),

babble about “master races”, “manifest destiny” and “exceptional nations”

modern Israel’s right to oppress Palestinians on the grounds that “God gave us this land,”

and by bitterest irony, the only too evident involvement of Christians in the Nazi holocaust, wherein Israel herself became the Amorite to be exterminated, while in German society at large Jewish wives of Aryan men became the “foreign women” who must be put away lest the purity of the race be compromised (cf. Ezra 10.1-12).

No, I’m afraid just saying, “Israel’s call to exterminate the Amorites is theological fiction,” won’t fix it.

As always when this kind of problem arises in Scripture, we must go further into Scripture itself. There are many voices in Scripture, and they don’t all say the same thing. Indeed, the Bible has a habit of giving us what Walter Brueggemann calls “testimony and counter-testimony”–one set of ideas and possibilities seeming to be presented in opposition to another, so that there is in effect an argument going on! Now I must be careful here. I’m not saying that everything in Scripture is up for grabs. Quite the contrary! There are some things—indeed, some fundamental things—that are quite clear and consistent and unambiguous throughout Scirpture, such as the proclamation of God’s faithfulness to Israel, and God’s grace and call to us in Jesus Christ. But there are other issues, important issues, where we seem to be listening to a debate.

So with the matters we are considering now. If we listen carefully to the Bible as a whole, we soon hear other voices telling us a story quite different from that implied by Joshua in our reading this morning– a story, moreover, that on Scripture’s own testimony is far older and deeper than Joshua’s, for it begins with the creation of the world wherein the Creator sees all that is made as very good (Gen. 1:31).

This story comes to fuller bloom in Genesis 9, where we discover that God’s primary covenant is not with God’s chosen people, nor even with humanity, but with “every living creature of all flesh”(9:9, 15). What’s more, this primary covenant is an everlasting covenant – beryt olam – it cannot be done away (9:16).

As for Israel as God’s chosen, Abraham is told what that means. Far from meaning that Israel is to destroy other nations, God tells Abraham that Israel being God’s chosen means the very opposite of that: “in your seed, all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Gen. 12:3; cf. 22:18). This idea is wonderfully developed in the Second Isaiah’s words to God’s servant— “It is too light a thing that you should be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to bring back the preserved of Israel; I will make you as a light for the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (49:6)—and these words are in turn said of the infant Christ by the aged Simeon in the Temple at Jerusalem–Simeon’s song that we recite every evening at the evening office: the Nunc dimittis. Jesus himself is the light to enlighten the nations, and also the glory of his people (Luke 2:29-32).

In investigating our scriptural passage this morning it seems then that we have noticed not one but two pairs of conflicting stories reflected in it about the world in which we live. One pair opposes a story in which God is our only saviour and Lord to a story in which we may worship many gods and many lords. The other opposes a story in which God cares for all that God has made to a story in which God cares only for those who have been named as God’s elect, the chosen people.

Of course, in neither case are the two stories simply set side by side as of equal merit. It’s perfectly clear in both Old and New Testaments that to accept the God of Israel as Lord is the only true path; to live by that other narrative, the narrative involving other gods, is to walk a path to destruction.

And as we have just noticed, there is good reason to argue that Scripture privileges the story of God’s universal generosity and good will over the story of God’s violence. Not only is it, as we’ve just seen, the original story, the story of creation: it’s also the final story – in the rabbinic canon of scripture the last word, quite literally. The closing word of the rabbinic canon – in our Christian Bibles the last word of 2 Chronicles – is ve-ya’al – “let him go up.” It is a word of grace, hope, and encouragement uttered to Israel, under God, by a pagan emperor who will with pagan funds rebuild the Lord’s Temple at Jerusalem: in other words, it speaks of nothing but good will between Israel and the other nations. And of course that aliyah – that “going up” to Jerusalem is the same aliyah, the same going up, that is promised in the prophets and the psalms to all the nations (Isa 2:2-4; Micah 4:2; Ps 72).

As for the New Testament, let it suffice for now to note that in it our Lord himself declares that when he is lifted up he will draw all people to himself, and the Letter to the Colossians declares that God wills to reconcile all things in His Son, bringing peace by the blood of his cross (John 12:32, Col. 1:20; cf. also Rom. 11:32, Eph. 1:10, 1 Tim. 2:3-4).

All that granted, it remains that our scriptures do not dismiss this story of God’s meanness nearly so clearly or straightforwardly as they dismiss the story that there are many gods whom we might worship. And the clearest evidence of that is that there remain to this day Christians in certain traditions who will claim that only those who are members of God’s people—and often that membership is defined by them quite narrowly—can have any hope of salvation. And such Christians can claim, not without reason, that they are following the Holy Scriptures, or at least a part of them.

This is not, of course, the only issue where it must be admitted that well-meaning people seem able to extract from the Bible entirely opposite stories. Another such has been slavery, where until late in the nineteenth century there were still those who would claim from the pulpit that God had ordained slavery, pointing to texts such as “Slaves obey your masters!” as justification for their view. Of course there were those who took the opposing view, pointing out that God had also said, “Let my people go!” It remains, however, that those who defended slavery were not totally without Scriptures to which they could appeal.

And still other issues remain hot button topics for some until this very day. Relationship between the sexes—patriarchy versus equality between the sexes—is one such issue, and same sex marriage another. Here, too, both sides find texts of Scripture to which they can appeal.

Why then do the Scriptures leave us with such confusion? Why, in the particular matters we have been considering this morning, do they leave us two narratives, so that we have to choose between them? Why did synagogue and church not simply expunge the narrative of God’s meanness and leave the only the narrative of God’s generosity – as, indeed, our Lectionary devisers may have been attempting to do by their omissions this morning?

The answer, I suspect, is quite simple. The people of God, now as in the past, are a work in progress. Those who created our Scriptures—those who wrote them and those, under God, who in the centuries following selected them to form the church’s canon—they themselves were a part of that work in progress. Our Lord promises in the gospel that the Holy Spirit will guide us into all truth (John 16:13 cf. 14:26). He does not promise instant awareness of all truth! Guidance is a process. So is teaching. Even St Paul admitted that he did not always know what to pray, or what to pray for[2]—which is as much as to say, he admitted that he did not always know what was right nor what was the will of God. Nor, of course is this process of becoming by any means confined to the people of God, however much we may rejoice in our chosen-ness. As the Apostle points out, God cares for all that God has made and desires that all shall come to a knowledge of the truth (1 Tim. 2:3).[3]

As always, then, we must be patient with those who came before us, with those who wrote our Scriptures and those who gathered them together, as well as with ourselves, with each other and with the church. And especially we must be patient over questions where persons of faith and goodwill have disagreed and may continue to do so. Even when we are broadly in the right over a particular issue, let us never forget that the chances are there is still more to be said, and that there are some things that we have not yet thought of and in this life perhaps never will! God has not finished with us yet–and that is not bad news, but good! In that hope and confidence, let us then confess our faith, as the church has taught us: We believe in One God…

[1] Jon D. Levenson, “Is There a Counterpart in the Hebrew Bible to New Testament Anti-Semetism?” Journal of Ecumentical Studies 22 (1985) 242-60.

[2] Romans 8:26. With St Jerome, the KJV and Douey-Rheims, I here translate Paul’s τί correctly, as opposed to the NRSV and other modern versions.

[3] I am reminded of Charles Kingsley saying all this rather nicely for young children back in the middle of the nineteenth century when he wrote of the ancient Greek myths:

Now, while they [the Greeks] were young and simple they loved fairy tales, as you do now. All nations do so when they are young: our old forefathers did, and called their stories ‘Sagas.’ I will read you some of them some day–some of the Eddas, and the Voluspa, and Beowulf, and the noble old Romances. The old Arabs, again, had their tales, which we now call the ‘Arabian Nights.’ The old Romans had theirs, and they called them ‘Fabulæ,’ from which our word ‘fable’ comes; but the old Hellenes called theirs ‘Muthoi,’ from which our new word ‘myth’ is taken. But next to those old Romances, which were written in the Christian middle age, there are no fairy tales like these old Greek ones, for beauty, and wisdom, and truth, and for making children love noble deeds, and trust in God to help them through.

Now, why have I called this book The Heroes? Because that was the name which the Hellenes gave to men who were brave and skilful, and dare do more than other men. At first, I think, that was all it meant: but after a time it came to mean something more; it came to mean men who helped their country; men in those old times, when the country was half-wild, who killed fierce beasts and evil men, and drained swamps, and founded towns, and therefore after they were dead, were honoured, because they had left their country better than they found it. And we call such a man a hero in English to this day, and call it a ‘heroic’ thing to suffer pain and grief, that we may do good to our fellow-men. We may all do that, my children, boys and girls alike; and we ought to do it, for it is easier now than ever, and safer, and the path more clear. But you shall hear how the Hellenes said their heroes worked, three thousand years ago. The stories are not all true, of course, nor half of them; you are not simple enough to fancy that; but the meaning of them is true, and true for ever, and that is—“Do right, and God will help you.” (Charles Kingsley, Preface to The Heroes, or Greek Fairy Tales for My Children [London: William Clowes, 1856]).

It may be worth my saying, incidentally, that I absolutely adored Kingsley’s The Heroes when I was about nine, and if anyone wants to introduce their children to the ancient Greek myths in a way that is not confusing for children who are being brought up as Christians, I can only say that The Heroes seemed to work for me (not, of course, that I thought about that at the time!). Kingsley was himself a devout Anglican priest, as well as a classical scholar, so this was an issue that mattered to him.

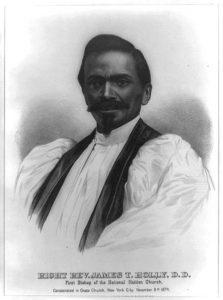

James Theodore Holly, Bishop of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Text of a Sermon preached by Professor Cynthia Crysdale in the Chapel of the Apostles on the 8th November 2017

If this sermon were to have a title it would sound a bit like a Dr. Seuss book: “Oh the Stories we tell!” I want to talk about three sets of stories today. The stories themselves are fascinating but my main focus is on just how these stories came to be, the meaning makers who generated them and the reasons they were crafted.

If this sermon were to have a title it would sound a bit like a Dr. Seuss book: “Oh the Stories we tell!” I want to talk about three sets of stories today. The stories themselves are fascinating but my main focus is on just how these stories came to be, the meaning makers who generated them and the reasons they were crafted.

James Theodore Holly was born a free African American in Washington DC in 1829. Baptized and raised in the Roman Catholic Church, Holly severed his ties when that denomination refused to ordain him because of his race. He joined the Protestant Episcopal Church while living in Windsor, Ontario, and after returning to the U.S. was ordained a priest in New Haven Connecticut. In 1874 he was consecrated as a missionary bishop of Haiti, becoming the first African American bishop in the Episcopal Church. In 1878 he attended the Lambeth Conference, the first Black to do so.

These are the facts. But within Holly’s story lies his passion for finding a voice for the voiceless. While he was living in Canada, he spent four years helping former slave Henry Bibb edit his newspaper, The Voice of the Fugitive. In the same year that he was ordained he co-founded the Protestant Episcopal Society for Promoting the Extension of the Church Among Colored People, a precursor to the Union of Black Episcopalians. He was determined to find a place, both literally and figuratively, for African Americans to thrive. Holly was a delegate to the first National Emigration Convention in 1851. He saw Haiti, a country where slaves had led a successful revolt and founded their own nation, as a place where Blacks could bind together. He believed that bringing Anglicanism to Haiti would contribute to its development. In spite of rebuffs from both Congressmen and the Board of Missions—several times over — in 1861 Holly took 110 men, women, and children from New Haven to Haiti.

The first year went badly. Forty-three of his emigrants died of infectious diseases, including his mother, his wife and his two children. He persevered nonetheless, becoming a Haitian citizen and eventually convincing the Board of Missions to sponsor his work. As Bishop he continued to live and work in Haiti, returning rarely to the U.S. He remarried and with his new wife Sarah, had nine children. He died in Port-au-Prince in 1911 and is buried there.

Holly worked to make a visible minority less invisible, in both church and society. But his story itself illustrates the way the Church has told its history. I learned about Holly by reading The Church Awakens: African Americans and the Struggle for Justice, a website of the Archives of the Episcopal Church.[1] This website was created in 1993 in response to the 1991 General Convention’s call to address institutional racism and its pattern of forgetting. Ironically, this pattern of forgetting arose as a post-civil rights era phenomenon. Having made structural and policy changes, the conscience of the Church seemed to be relieved of the need to remember the “historic harm of three centuries of racism.” The Archives mined its resources to recover what were otherwise lost memories. The stories they tell are as disturbing as they are enlightening: holy women and men such as Holly are brought to light, but the recalcitrance of embedded prejudice in the church is most visible. Sewanee plays its part here, and we have much to do still to repent, retrieve and renew our history.

The second example of storytelling comes from our Old Testament lesson today. The Book of Deuteronomy stands as a bridge between Sinai and the Promised Land. Set in the moments just before Israel moves to cross the Jordan, its theme is obedience and loyalty. The future dangers that are highlighted are not so much from warfare but from success: the dangers of adopting foreign gods and worshipping at local shrines. A second telling of the law (deuteros nomos—hence “deutero – nomy”) is a necessary reminder to establish again the covenant relationship between God and God’s people.

But while law and rules and obedience are the main threads, they are woven with narrative wool. How many of you have children who complain about rules: “Who does which chores? Why do I have to wash my hands? Brush my teeth? Go to church?” Deuteronomy tells us that the way to respond to such questions is to tell a story. When your children ask you, “What is the meaning of these decrees and statutes?” you must tell them, “We were Pharaoh’s slaves in Egypt, but the Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand. The Lord displayed before our eyes great and awesome signs and wonders against Egypt, against Pharaoh and all his household” (Deut. 6:21-22). This narrative context is repeated at the end of Deuteronomy. “When you bring the first fruits of the harvest as a thank offering to the priest, you shall say: ‘A wandering Aramean was my ancestor; he went down into Egypt and lived there as an alien, few in number, and there he became a great nation, mighty and populous. When the Egyptians treated us harshly and afflicted us, by imposing hard labour on us, we cried to the Lord, the God of our ancestors; the Lord heard our voice and saw our affliction, our toil, and our oppression. The Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with a terrifying display of power, and with signs and wonders; and he brought us into this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey’” (Deut. 26:5-9).

But let us notice that this narrative also has its dark side. Just after the passage in Deuteronomy 6, chapter 7 continues with instructions about how to treat the neighbours in the Israelites’ new home. Once God has cleared away seven mighty nations from the land, “when the Lord your God gives them over to you and you defeat them, then you must utterly destroy them. Make no covenant with them and show them no mercy. . . . this is how you must deal with them: break down their altars, smash their pillars, hew down their sacred poles, burn their idols with fire” (Deut. 7: 2, 5). Yes, the theme is that God alone must garner the loyalty of Israel. But there is no avoiding the fact that God is ordering genocide. Our Biblical tradition – the stories we have told of God’s gracious work – are filled with prejudice that our generation must acknowledge. While we cannot change history, we can face the dark side in our heritage with honesty. We need to be attentive: we must read between the lines and, while not excusing the past, at the very least take care not to hand on embedded intolerance.

My third example of story telling is about making meaning in the present as events unfold in the midst of confusion. When the twin towers were attacked on 9/11 U.S. airspace was quickly closed and all planes in the air ordered to land. A number of commercial flights were over the Atlantic – too far along to return home. The closest airfield was in Gander, in Newfoundland: an airfield very much in use during World War II but rarely used in recent decades. One by one planes from London, Dublin, Frankfurt, and Moscow, among others, were ordered out of the sky, most pilots still ignorant of the reason why. In all, 38 jumbo jets landed in the space of a few hours, carrying 6500 passengers and crew, 17 dogs and cats and 2 rare bonobo chimps. The population of Gander is itself just under 10,000. But it became clear as this drama unfolded that those planes were not going to take off again anytime soon.

The people of Gander and surrounding fishing villages did not see potential terrorists or imminent danger. They saw people in need and set out to help them. The people who disembarked – some after 28 hours on a plane – came from 100 different countries with thousands of different reasons for traveling that day. There were refugees from Moldova on the way to a new life in the U.S.; several couples coming home with newly adopted children from Russia; a high-profile executive from the elite fashion designer, Hugo Boss, en route to New York for fashion week; Lenny O’Driscoll, who had grown up in Newfoundland but hadn’t been back for decades. There were Muslims, Christians and Jews, gay couples, young and old, single and married. One couple who met that day fell in love and were eventually married.

The people of Gander and surrounding fishing villages did not see potential terrorists or imminent danger. They saw people in need and set out to help them. The people who disembarked – some after 28 hours on a plane – came from 100 different countries with thousands of different reasons for traveling that day. There were refugees from Moldova on the way to a new life in the U.S.; several couples coming home with newly adopted children from Russia; a high-profile executive from the elite fashion designer, Hugo Boss, en route to New York for fashion week; Lenny O’Driscoll, who had grown up in Newfoundland but hadn’t been back for decades. There were Muslims, Christians and Jews, gay couples, young and old, single and married. One couple who met that day fell in love and were eventually married.

All were welcomed. The school bus drivers, who were on strike, left their picket lines to ferry the “Plane  People” to a host of school gyms, church basements, and a Salvation Army camp in the woods. Bakeries went into overdrive, pharmacies cleared their shelves of toiletries, and casseroles came out of ovens by the dozens. What will live in memory as a day of terror and grief, became at the same time a day of comfort and healing. The stories abound and have been collected into a book called The Day the World Came to Town,[2] now made into a Tony awarding winning Broadway musical – Come from Away.[3]

People” to a host of school gyms, church basements, and a Salvation Army camp in the woods. Bakeries went into overdrive, pharmacies cleared their shelves of toiletries, and casseroles came out of ovens by the dozens. What will live in memory as a day of terror and grief, became at the same time a day of comfort and healing. The stories abound and have been collected into a book called The Day the World Came to Town,[2] now made into a Tony awarding winning Broadway musical – Come from Away.[3]

Of all the stories, one has had an especially compelling ring for me. During the second day at the Elementary school in Glenwood, one of the volunteers noticed that a man and two women had not eaten any of the food put before them. When she enquired about this, it turned out that they were Orthodox Jews. The Jewish population of Newfoundland is miniscule but the hosts helped Rabbi Levi Sudak set up a Kosher kitchen in the faculty lounge of the school. The Rabbi had been en route to New York, where the founder of his particular Jewish sect is buried. His intention was to visit the grave and return home to London where he works with disenfranchised youth. Now he wondered what God had in store for him. Why deposit him on this rock in the Atlantic with no fellow Jews in sight? As the week moved on his question intensified. By the time his plane was released to fly again it was Friday evening – neither he nor the two other Orthodox women would travel on the Sabbath. As his plane took off for New York without him, he wondered again why he had come to this isolated Gentile island.

The next day a man called Eddie Brake came to visit him. Eddie Brake was over 70 years old. He was born to a Jewish mother and father in Poland in 1930. He did not know what name his parents had given him or even their family name. He only knew that just prior to WWII his parents had arranged to have him smuggled out of Poland to England. He was adopted by an English couple, who then moved to Cornerbrook, Newfoundland. He was told never to let anyone know that he was Jewish. If he mentioned it at all his parents beat him. Even as an adult, when he decided to tell his wife and grown children of his identity, they scorned him and hushed him up. Now, here he was after all these years, sitting in front of a Rabbi. He told him that all these years he had never stopped thinking of himself as a Jew. His walking stick had engraved on it a small star of David. Sometimes at night he would wake up singing the religious music he had learned as a child. Eddie and the Rabbi talked for over two hours. When they were done, Eddie returned home and the Rabbi made plans to return to London. He never got to New York, but he now knew why he had made this journey.

The story of that week in Gander Newfoundland is a story of having to create meaning in the midst of tragedy, with people who had never intended to come together. There was tension for sure – the narrative unfolded in a context in which it was not clear whether these planes themselves were intended as weapons, or whether some of the passengers were terrorists on a mission. But those who lived on that particular rock in the Atlantic reacted as if those who descended on them were their own mothers, fathers, children, grandchildren, neighbours. No hatred, no anger, no fear of those who come from away.

We cannot avoid the terror of memories that haunt us. As a community, we have the task of owning the dark places of our past and living in the midst of current grief and sorrow. Each of us has secrets we don’t tell, sins we avoid recalling, resentments or fears that linger in deep places. But as disciples of Christ it is our job to tell stories – to find the gospel and preach the gospel ever anew. What if we lived AS IF resurrection could illumine the very darkest places of our past? What if we lived AS IF the Lord ruled even the tragic present? AS IF nothing could separate us from the love of God? AS IF we could meet everyone without fear? AS IF those who come from away are in fact our dearest neighbours?

[1] Go to https://www.episcopalarchives.org/church-awakens/

[2] Jim DeFede, The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland (New York: Harper Collins, 2002).

[3] Come from Away, book, music and lyrics by Irene Sankoff and David Hein.