Thoughts on Jeremiah after hearing Propers 23 and 24, Year C

The prophet Jeremiah isn’t generally associated with being particularly upbeat or cheerful. The prophetic book that bears his name is dominated by his predictions of doom and destruction for Israel and her king, and the other Biblical book associated with him—Lamentations—though not actually by him, is a series of poetic laments over that destruction after it’s happened. It’s surely not an accident that Jeremiah’s name has entered the English language in the word “jeremiad”—which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “a very long sad complaint or list of complaints.”

The prophet Jeremiah isn’t generally associated with being particularly upbeat or cheerful. The prophetic book that bears his name is dominated by his predictions of doom and destruction for Israel and her king, and the other Biblical book associated with him—Lamentations—though not actually by him, is a series of poetic laments over that destruction after it’s happened. It’s surely not an accident that Jeremiah’s name has entered the English language in the word “jeremiad”—which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “a very long sad complaint or list of complaints.”

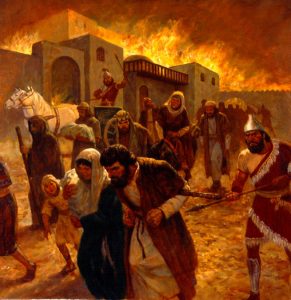

Yet the readings from Jeremiah that we had last Sunday and this are actually rather hopeful and encouraging in tone, even though they date from a time when all Jeremiah’s gloomy prophecies have come to pass. Jerusalem has fallen to the armies of Nebuchadrezzar, Israel is now in thrall to the pagan empire of Babylon, and many of her citizens have been forcibly deported to Babylon.

But in last week’s passage, in a letter addressed to the exiles in Babylon, the prophet told the exiles that even though they were in a land characterized by the prophets Amos and Hosea as polluted (Hos. 9:3-4, Amos 7:17b), still God had not forsaken them (29:11-14). They might flourish there, and indeed had a duty to do so. Let them build, plant, and marry (29:5-6). Let them continue to pray in the expectation that God would hear them (29:7b, 12-14a).

If you’ve read the whole of this section in Jeremiah, you’ll know that Jeremiah’s letter to the exiles is not only set in the context of Israel being subject to Babylon, it’s also set in the context of Jeremiah’s opposition to a false prophesy. And we know exactly what that prophecy was. In chapter twenty-eight we hear the prophetic words of one Hananiah ben Azzur. In a scene that’s striking even when we read about it all these centuries later, Hananiah takes the wooden yoke that Jeremiah is wearing as a symbol of submission to Babylon, and in a gesture of dramatic and prophetic power, breaks it, and then speaks what he says is the LORD’s word: “Even so will I break the yoke of Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon from the neck of all the nations within two years” (28.11).

It is a powerful moment.

But then Jeremiah receives a quite different word. Jeremiah produces an iron yoke, and declares: “Thus says the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel: I have put upon the neck of all these nations an iron yoke of servitude to Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon, and they shall serve him, for I have given to him even the beasts of the field” (28:15).

In other words, Babylonian imperial rule is, for the present, the will of God.

It’s in that context that Jeremiah tells the exiles to flourish in Babylon. And the terms in which he does so are significant. They are to build, to plant, and to marry – the precise terms in which God’s people are granted exemption from participating in holy war (Deut. 20.5-7; compare 1 Macc. 3.55). The point is, Hananiah’s opposition to Jeremiah was the opposition of a zealot, a violent revolutionary who called on Israelites to draw their swords in a holy war to end the yoke of Babylon. Jeremiah’s response is that the faithful Israelite is exempt from such a war. The argument is both political and theological: how to be the people of God in a strange land.

Yet Jeremiah goes even beyond that, even beyond nonviolent nonresistance. Most striking of all, he tells the exiles to pray for Babylon, heathen though it is, seeking the good of the city where they find themselves (29:7). As Jeremiah makes clear, such prayer is by no means devoid of self-interest: “for in its welfare you will find your welfare” (29:7b). Even so, the fact remains that personal longing for revenge and national desire for retribution are overcome, and instead we have by implication the formation of a new fellowship with the heathen through prayer for them. The very humiliation and exile of Israel has served in Jeremiah’s consciousness, to strengthen his understanding of the greatness and universality of God, and his sense of God’s relationship to all peoples.

So then to this morning’s passage. Jeremiah is still addressing an Israel defeated and in exile. He quotes the despairing words of some in that situation: “The parents have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge.” Later students of the texts have often seen these words as some kind of theological claim about guilt of one generation being a burden to another. Personally, I doubt that those who said them meant anything so sophisticated. I think they were simply saying, “We screwed up when we were a free people under our own king in our own land, and now we’re paying the price. God doesn’t care about us any more.” And it’s to people in THAT situation, again, that Jeremiah says, “No, you’re wrong. God does still care about you.”

The days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah. It will not be like the covenant that I made with their ancestor… a covenant that they broke…

Precisely what Jeremiah thought this new covenant might look like he doesn’t say. Perhaps he didn’t have any very clear idea himself. Of course we Christians associate it with the grace that we find in Jesus Christ, and I think we’re right to do so. But Jeremiah was, I think, simply asserting a basic truth—a truth that is indeed vindicated in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus, as Saint Paul constantly reminds us—namely, that GOD IS FAITHFUL, even when we are unfaithful! “If we are faithless, he remains faithful, for he cannot deny himself” (2 Tim. 2:13).

Israel, like all nations, including our own, can always find a good reason to give up on God. It may give up on God because of pride and conceit:

My power and the might of my own hand have gotten me this wealth (Deut. 8:17).

In other words, it may give up on God because it takes itself and its own achievements far too seriously. Or it may give up on God because it decides that God has abandoned it, and so despairs:

I am one who has seen affliction under the rod of God’s wrath; he has driven and brought me into darkness without any light; against me alone he turns his hand, again and again, all day long… (Lam. 3:1-3)

In other words, Israel may give up on God because it takes its enemies and their achievements—and even, perhaps, its own sins?—far too seriously. Either way, in pride or despair, Israel needs the prophets to remind her who she is. To be precise, the prophets remind her, first, that it is the LORD God Who is the center of her life, and the LORD God does not change. And second, as Jeremiah told us last week, that Israel who knows God must pray for those who do not know God, even for those she thinks of as her enemies, because God’s concern for her is not incompatible with God’s concern for all: because the well-being of all is, indeed, Israel’s well-being.

In all this, we may note, God appears to have very little concern with Israel’s greatness, at least as the world counts greatness. Indeed, God appears rather to scorn such greatness:

It was not because you were more numerous than any other people that the Lord set his heart on you and chose you—for you were the fewest of all peoples. It was because the LORD loved you… (Deut 7:7)

Or again, as Our Lady reminds us in the Magnificat, God has what many may regard as a somewhat irritating habit of casting down the mighty, and exalting the humble and meek. Indeed, when one contemplates God in Christ hanging from the cross, it almost looks as if God likes losers.

He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God? (Micah 6:8)

Understandably, Israel’s prophets, those who speak from the midst of Israel, most often present God’s command as a requirement referring to the well-being of Israel herself (e.g. Isa.47.6). But sometimes (and very interestingly) they imply a more general command for justice and courtesy among all the nations. They suggest that there is at work in the world an upholding and defence of human rights that in the end even the most ruthless and powerful will not be able resist. That, I think, is what the Scriptures mean when they say that God “shall judge the world with righteousness, and the peoples with his truth” (Psalm 96:13); and to live in accordance with that hope is what it means to love mercy, do justice, and walk humbly with your God.

And woe betide Israel, or any other nation or group, that forgets these things!

4 Comments

Comments are closed.

Thank you for this. No surprise, “you’ve done it again.” Ever so often, I think I get tired “of the Way,” but in reflection, I guess in reality, I just get tired “in the Way.”

May I be so bold to note that you are, and continue to be a gift?

Thanks, Don, as always! God bless you.

Great post! Have nice day ! 🙂 z3f73

Thank you! You too! Sorry to have been slow replying.