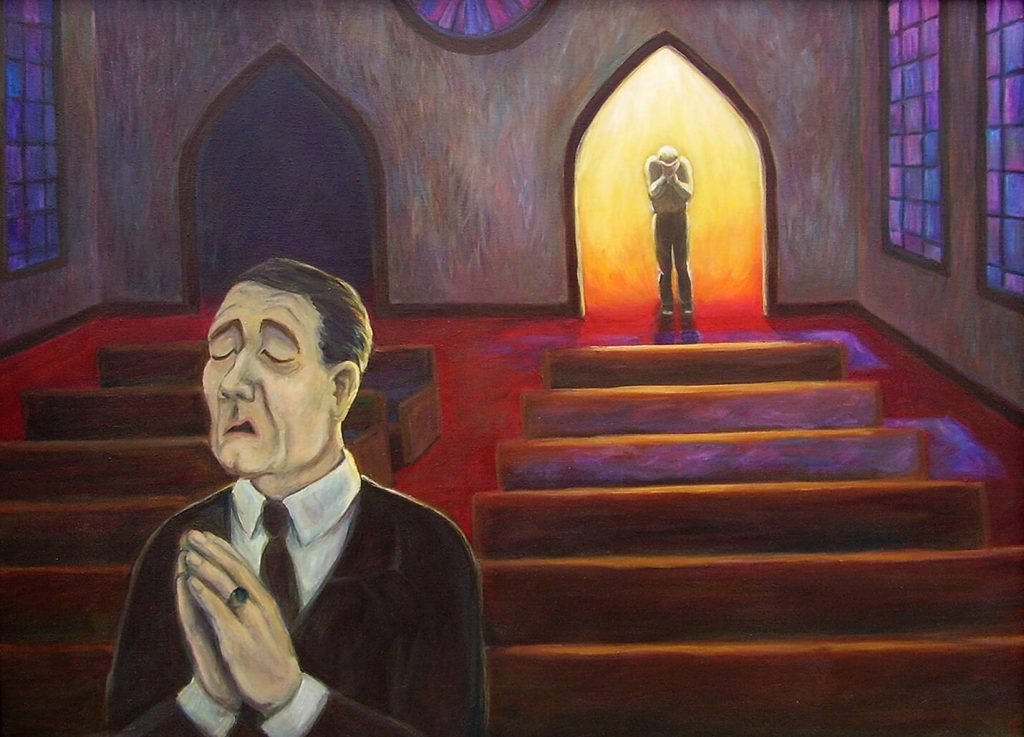

The Pharisee and the Publican. Notes for a sermon preached at St Olave’s Church, Exeter, on the Last Sunday after Trinity

For the Psalm: 84.1-7; the Gospel: Luke 18.9-14

The parable of the Pharisee and the Publican! It’s a simple tale, isn’t it? I’ve heard of a priest one Sunday who had to preach on it. He was in good form and told the story well, with just such touches of humour and occasional rhetorical flourishes as kept his hearers interested—indeed, more than interested! He had them in the palm of his hand. He sensed that it was a moment to be seized, a moment for all to be roused to new levels of spirituality!

“So, dear friends,” he said in conclusion, “let us thank God that we are not like that Pharisee…”

A simple tale!—but perhaps for us deceptively simple. To begin with, we must face the fact that for centuries it’s been used to caricature our Jewish friends in general and the Pharisees in particular. So by way of clearing the ground let’s say at once that that is not what it is about. Our Lord presents in the Pharisee a person whom his hearers would naturally have regarded as “good” (and with good reason) and compares and contrasts him with someone whom they would have regarded as “bad” (also with good reason).[1] If we were telling a modern version we might contrast, say, a faithful church person and a shady businessman who pulls off sleazy deals. And what makes the story interesting is not that Pharisees are actually bad people and tax collectors good but rather that this is a story in which the “good” person gets it wrong and the “bad” person gets it right! Which of course does sometimes happen. So live with it!

So what happens in the story?

We see two men who do, it seems, have something in common. Indeed, they have it in common with our Psalmist this morning:

How lovely is your dwelling place, O Lord of hosts!

My soul has a desire and longing to enter the courts of the Lord.

What they have in common is that they both go the temple to pray.

But there the resemblance between them ends.

We see the good churchman—let’s call him that to make sure we don’t fall into any of the traps we have created for ourselves over the word “Pharisee”—we see the good churchman “standing”, or even, “taking his stand”. Luke’s Greek is very formal and studied. But it is also ambiguous. The sentence as a whole can be taken to mean either that he was “standing by himself” (as our NRSV translation this morning has it)—in other words, he was deliberately keeping himself apart from everyone else—or else that “standing, he prayed with (or to) himself” (a common Greek idiom—as when in English we say that someone “said something to themselves”).[2] In which case we have a delicate—and, I would say, characteristically Lucan—irony: the prayer, ostensibly intended for God, actually travels no further than the man who prays it. Personally, I think we have no need to choose between the two. Luke’s ambiguity is deliberate, and he intends to hint at both.

The prayer begins with our good churchman giving thanks to God for all that he is. Very proper! Give God the glory! But then it rapidly descends into caricature as the “glory” turns out to be entirely a highlighting of his own virtues. His words have the form of a thanksgiving but they are actually a piece of self-justification: what a friend of mine yesterday taught me to call “humblebrag”—a splendid word that I had not heard before! The virtues that our churchman claims are matters of formal religious piety, like fasting twice a week—which, incidentally, was not required of any Jew. But there are, strikingly, no works of simple charity or mercy among them. So, if we were telling this story in our modern version, we might say that here is someone who goes daily to Eucharist in the Cathedral, is scrupulous in reciting daily Morning and Evening Prayer and makes big donations to the church, but never does anything to help the poorer members of his family or so much as gives a fifty-pence piece to beggars as he walks by them in the street. Indeed, our man is proud of his difference from and indifference to such persons: “thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even this tax-collector” he calls them. The Greek οὗτος – “this”—is emphatic and contemptuous. I am nothing like this scurvy fellow!

What then of our sleazy businessman? A very different picture! He stands “far off” and will “not even look up to heaven”. He’s well aware how unworthy he is to be in the presence of God! In antiquity it was generally the custom for women to beat their breasts in mourning rather than men. But he stands “beating his breast” and praying, “God, be reconciled to me, a sinner!” (18.13). I’m reminded of another scene in the gospel. Simon the Pharisee presides at table over our Lord, while a woman of the streets who is a sinner weeps over his feet, washing them with her tears and kissing them and drying them with her hair.

“That woman who’s touching him is a sinner. He ought to know that,” says Simon to himself.

“She loves much,” says our Lord, reading his thought, “therefore it is evident that her sins, which are many, are forgiven” (Luke 7:47).

So now, says Our Lord, this man—the Greek οὗτος is as emphatic here as it was when the Pharisee used it, but no longer contemptuous—this man who claims nothing and offers nothing but his repentance “went down to his home justified, rather than the other.” The tax collector goes back to his world, but he is no longer the same man. Clearly, God is at work in him! Again, we may be reminded of another sleazy business man who is mentioned later in the gospel: a tax collector called Zachaeus who also repents and of whom our Lord says, “This day salvation has come to this house, for he also is a Son of Abraham” (Luke 19.9). God shows Himself to be what Ezekiel declared God to be: a God who does not wish anyone to die (Ezek 18.32).

So where are we to see ourselves in this story? Ah, well, that’s where we have to be careful! Luke surely gives us a clue before the parable even starts. Our Lord told it, he tells us, “to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt” (18.9). And who were they? Luke doesn’t say—automatically, perhaps, we think, “it’s the Pharisees!” (cf Luke 15.2). But the fact is, on this occasion Luke doesn’t say that, so perhaps he wants us to think a little more carefully? After all, who is more likely to be listening to Jesus or even studying the gospel than a disciple? And who is more likely than a disciple, who is more likely than us, who is more likely than me, to be “trusting in myself that I am righteous”? Of course we regularly say that we know we are sinners, but in our hearts, how easy it is for us to slip into something quite different! “Actually I’m a pretty good chap. Look at all I do! I must have run up a pretty good credit balance with the Almighty. Not like all those outsiders and rogues!” Well, says Jesus through the parable, guess what! Your credit balance with God doesn’t matter. That’s not what life is about! You can’t earn God’s love by being a superior sort of person!

Now this message may at first seem disappointing. Why then should I bother? Does doing one’s best actually matter? Does it make any difference to anything whether or not we try to be true or honest or kind?

Well, yes, of course it makes a difference. Apart from anything else, it makes a difference to us, to me, to what we are. It’s how we become truly human. It’s about finding out what we are truly meant to be. But if we think about it a little more, it may occur to us that the fact that God’s love for us doesn’t depend on our virtues is also very freeing.

Consider this: let us say that you are loved because you are beautiful. That’s nice. But what then when you grow old and are no longer beautiful? Will you no longer be loved?

You are admired because you are clever. That’s nice. But what then when you make a mistake, as no doubt you will do one day? Nobody is right all the time!

You are loved because you are good. That’s nice. But what when you have an off day and are bad?

You are loved because you are loveable. That’s nice. But what when you are unlovable?

The essence of the gospel was summed up in God’s word to Israel through Moses:

It was not because you were greater than any other people that the LORD set his heart on you and chose you—for you were the least of all peoples. It was because the LORD loved you (Deut. 7:7-8a)

Of course God wants us to be good. But the gospel truth is that God’s love is unconditioned by our goodness—or lack of it.

So where does that leave us? What are we to do with our lives? Surely we’re not to spend all our time beating our breasts! But equally, we’re not to our spend time ostensibly thanking God while actually congratulating ourselves! I can be pretty sure I’m not by any means the man God wants me to be, and at the same time pretty sure that at the end of the day it’s not up to me to judge. By all means let’s give God the glory on those rare occasions when we may actually seem to have got something right. Beyond that, let’s do our best to be as loving and useful as we can, and commend our failures to God’s mercy. When all is said and done, we can never truly tell how anything we do, however well or ill intentioned, is actually going to work out. But we do trust that God can do amazing things even with the worst material, and we dare hope that God may bring God’s glory and peace even out of our screw-ups. That was the faith of the tax collector, and at the end of the day, despite his pomposity and self-congratulation, we may dare hope it was the faith of the Pharisee too. In which faith and hope let us now declare our own faith, as the church has taught us: We believe in One God…

[1] The story has a shape that Greek rhetoricians called σύγκρισις—“comparing” or “comparison”—a form which they held in high regard.

[2] So the RV. Max Xerwick S.J. and Mary Grosvenor suggest that we render πρὸς ἑαυτὸν by “within himself” (Grammatical Analysis of the New Testament [Rome: Editrice Pontificio, 1993] 254; cf. Christopher Evans, Luke [London: SCM, 1990] 642-43). It should be conceded that the text is difficult and, perhaps as a consequence of that, uncertain: cf. François Bovon, Luke (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2013) 2.546-7, Martin M. Culy, Mikael C. Parsons and Joshua J. Stigall, Luke: A Handbook on the Greek Text (Baylor, 2010) 568; Bruce M. Metger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (London: United Bible Societies, 1975) 168.