Saint Nicholas of Myra: text of a sermon preached by Robert MacSwain in the Chapel of the Apostles on the 6th December 2017

For the Proper: Proverbs 19:17, 20-23, Psalm 145:8-13, 1 John 4:7-14, Mark 10:13-16

For the Proper: Proverbs 19:17, 20-23, Psalm 145:8-13, 1 John 4:7-14, Mark 10:13-16

You disgust me. How can you live with yourself?

You sit on a throne of lies.

You’re a fake.

You stink. You smell like beef and cheese.

You don’t smell like Santa.

Yes, the classic “You Sit on a Throne of Lies” scene from the great 2003 film Elf, starring Will Farrell as Buddy, the human being who grew up at the North Pole believing himself to be one of Santa’s elves—despite the fact that he’s twice as big as everyone else.

In this famous scene he unmasks—or rather un-beards—a department store Santa as an imposter, not the real Santa Claus at all, whom Buddy of course knows personally. But while Buddy’s righteous anger at the hapless impersonator is certainly amusing, to me this scene is not quite as funny as Buddy’s unfortunate later encounter with a very pre-Game of Thrones Peter Dinklage as a children’s book author whom Buddy innocently calls an “angry elf” with calamitous results.

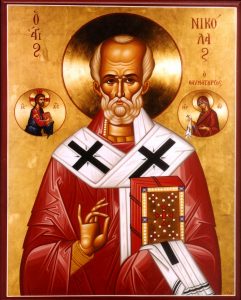

Now, if Dr King were preaching on St Nicholas of Myra, I’m sure he would tell us all about the actual history of this fourth-century bishop who was born in modern-day Turkey, persecuted under Emperor Diocletian, attended the Council of Nicaea (where according to tradition he was so angry at Arius that he slapped him), who was famous for his pastoral concern for the poor and vulnerable, whose generosity gave rise to many pious stories and legends, and who later became the patron saint of children, students, sailors, brewers…among other occupations…as well as various cities and countries. St Nicholas actually made the news earlier this year when archeologists announced that they may have found his intact tomb in Myra, where he was bishop, rather than Bari in Italy where it was long thought his relics had been taken. But wherever his remains lie, Nicholas died on December the 6th in 343, so today marks the one thousand six hundred and seventy-fourth anniversary of his death.

St Nicholas is often valorized as someone who combined a firm commitment to economic justice with a rigorous doctrinal orthodoxy. Hence our texts from Proverbs—“Whoever is kind to the poor lends to the LORD” (a remarkable thought!)—and the First Letter of John, which explains how the eternal love of God became incarnate in Jesus (paradigmatically, the first Christmas present): “God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him.”

So there is indeed much of value to be said about Nicholas. But as a mere theologian rather than a church historian, my primary interest this morning is focused less on the historical St Nicholas of Myra as on the figure he later became, namely Santa Claus. And, in particular, the way in which in popular culture the disputed existence of Santa Claus is often used—more or less obviously—as a proxy for debates about the existence of God.

This sotto voce association between God and Santa goes back at least to 1897, with Francis Pharcellus Church’s famous editorial, originally titled “Is There a Santa Claus?”, responding to a letter from eight year-old Virginia O’Hanlon. Virginia wrote that some of her “little friends” disbelieved in Santa and thus asked the newspaper editor if he was real. The first two paragraphs of Church’s response go like this:

Virginia, your little friends are wrong. They have been affected by the skepticism of a skeptical age. They do not believe except they see. They think that nothing can be which is not comprehensible by their little minds. All minds, Virginia, whether they be men’s or children’s, are little. In this great universe of ours man is a mere insect, an ant, in his intellect, as compared with the boundless world about him, as measured by the intelligence capable of grasping the whole of truth and knowledge.

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! how dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus. It would be as dreary as if there were no Virginias. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence. We should have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished.

Now the great irony here is that Church himself was a skeptic and atheist, but when confronted with a question from an eight year-old he could not bring himself to speak what he regarded as the real truth to poor little Virginia: namely that there is no Santa, we’re all going to die, and life is ultimately meaningless. And thus despite his personal cynicism Church wrote what has become, according to the Newseum in Washington, DC, “history’s most reprinted newspaper editorial, appearing in part or whole in dozens of languages in books, movies, and other editorials, and on posters and stamps.”

Although it is never cited directly, basically the same perspective as Church’s editorial forms the basis of the classic 1947 film Miracle on 34th Street, in which a man calling himself Kris Kringle and claiming to the one true Santa Claus meets a divorcée named Doris (played by Maureen O’Hara) and her daughter Susan (played by a young Natalie Wood). Early in the film, Doris’s love-interest Fred is shocked to discover that Doris is raising Susan to be completely rationalistic in her approach to life. So Fred asks Doris, “No Santa Claus, no fairy tales, no fantasies of any kind. Is that it?” And Doris replies, rather briskly: “That’s right. I think we should be realistic and completely truthful with our children, and not have them growing up believing in a lot of legends and myths, like Santa Claus for example.”

Doris is thus deeply distressed to discover that Mr. Kringle, the kindly old man who looks just like Santa Claus, thinks he really is Santa Claus. Her only conclusion is that he must be crazy—so he is institutionalized in a mental hospital. Fred, a lawyer, takes it upon himself to get him out, which means proving in court that Mr. Kringle is not crazy after all. When Doris and Fred have a big argument about all this, Fred echoes Church’s editorial: “Faith [he says] is believing in things when common sense tells you not to….[Things like] Kindness and joy and love and all the other intangibles” that make life meaningful.

My third and final example is the film I began with, Elf. We are told at the start of the movie that Santa’s whole mission of toy delivery is in grave danger. Santa’s sleigh flies on “Christmas spirit” (let the reader understand) and when “Christmas spirit” runs out due to general cynicism and skepticism, the sleigh is grounded. Each year fewer and fewer people believe in Santa, which has created a serious energy crisis. But if enough people do believe in Santa, the sleigh will fly and presents will be delivered. However, such belief cannot be based on empirical evidence: as Santa says to a little boy in the film, “Christmas spirit is about believing, not seeing. If the whole world saw me all would be lost.”

Now my point here is the simple observation that in Church’s editorial, in the debates between Fred and Doris in Miracle on 34th Street, and in the lack of “Christmas spirit” in Elf, the real topic being discussed, if only subliminally, is not in fact Santa Claus but God. It is God who has been placed in the mental asylum of our intellectual culture, God whose sanity must be questioned within the court of common sense, God whose existence must be justified—if at all—not through hardheaded reason and empirical observation but through…what? What precisely is the operative epistemology at work here in Church’s editorial and these films?

Well, at best it seems to be simple unquestioning faith, but at worst it seems to be merely pragmatic sentimentality and nostalgia for the naivety of childhood. We live in a dry and disenchanted age: our culture has fallen away from genuine religious belief, but we’re still worried enough about our skepticism that the question keeps emerging in rhetoric about “Christmas spirit”: apparently belief in God is like belief in Santa Claus—both are equally crazy or unfounded, but well…who cares? We’ll never know anyway. So pass the eggnog and keep the season bright.

At this point in my sermon I turn somewhat desperately to the thus-far-neglected gospel lesson,

When what to my wondering eyes should be seen

But Mark, Chapter ten, beginning with verse thirteen:

People were bringing little children to Jesus in order that he might touch them; and the disciples spoke sternly to them. But when Jesus saw this, he was indignant and said to them, “Let the little children come to me; do not stop them; for it is to such as these that the kingdom of God belongs. Truly I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will never enter it.” And he took them up in his arms, laid his hands on them, and blessed them.

Well, by St. Nicholas, I have to admit that this is not quite the operative epistemology that I was hoping for. Doesn’t all this “receive the kingdom of God as a little child” business play right into the hands of the sentimental cynicism that I’ve been tracking since 1897? Or is all that stuff sentimental cynicism after all? I mean, what’s the difference between Santa’s response to the boy in Elf—“Christmas spirit is about believing, not seeing”—and Jesus’ response to Thomas, “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe”?

We need to tread carefully here, because what might not be good reasons to believe in “Christmas spirit” might actually be good reasons to believe in God or the resurrected Christ. Whether or not it is rational to believe something depends partly on the object of belief and not just on the offered reasons. These are dark and difficult matters. But there is an important difference between, say, Church’s editorial and Mark’s gospel, on how they view the crucial perspective of children.

The world to which Jesus belonged did not value childhood as such, which is why the disciples tried to discourage the parents from bringing their children to Jesus, and so in his words and actions Jesus offers a profound transformation of values: there is something, he says, essential to the character of a child that is necessary for those who would belong to the kingdom of God. So what is it?

I suggest that the childlike character Jesus endorses here is being open and receptive to the Word of God and the Gospel of Christ. The technical term for this in Catholic theology is docility: according to Thomas Aquinas, docility is part of prudence, and is a moral and intellectual virtue necessary for us to learn anything new from a parent or teacher: children and students without docility cannot learn and grow in knowledge. Jesus is not telling us to be child-ish, but he is telling us to be child-like, docile, “for it is to such as these that the kingdom of God belongs.”

By contrast, 1800 years later, Francis Church has a wildly exaggerated view of the importance of childhood: without the innocence of Virginia and her little friends, he says, “The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished.” But now childhood itself, rather than Christ, has become the light of the world. And yet in making this claim Church is himself in bad faith: he doesn’t believe what he is telling Virginia, and in fact when the editorial was originally published he refused to print his name with it so it appeared anonymously.

We are called to be a different Church than Church. The light we proclaim is not the light of childhood but the light of Christ. The Spirit we proclaim is not the “Christmas spirit” but the Holy Spirit, for by this “we know that we abide in him and he in us, because he has given us of his Spirit.” And we prove ourselves to be true venerators of St Nicholas of Myra by our compassionate generosity to the poor and vulnerable, the weak and the oppressed, those without voice or agency.

But maybe, just maybe, instead of slapping heretics, tempting as that might be, perhaps we should instead follow Buddy’s friendlier example, reach out our arms and ask them: “Does someone need a hug?” (But remember: if they say no then leave them alone!)