Good Shepherds, Bad Shepherds and Dividing Walls

Proper 11 Year B. For the OT, Jeremiah 23:1-6; for the Psalm, Ps. 23; for the NT, Ephesians 2:11-22; for the Gospel, Mark 6:30-34, 53-56

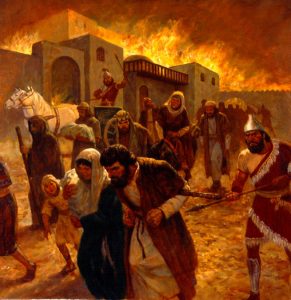

For our first reading this morning we have a little group of oracles from the Book of the prophet Jeremiah. They were composed, I dare say, about two and a half thousand years ago, but they surely still speak to us in this year of grace 2018. The first of them looks back to the kings who had led and misled Judaea up until the disasters of her defeat by the Babylonians in 587 BC, the destruction of Jerusalem and the carrying of her people into exile:

Therefore, thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, concerning the shepherds who shepherd my people: It is you who have scattered my flock, and have driven them away, and you have not attended to them. So I will attend to you for your evil doings, says the Lord.

A dreadful warning for the false shepherds! But that doesn’t mean God has forgotten his people, or given up on them. The final oracle that we heard is by contrast a message of hope: God promises a true shepherd:

The days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch… And this is the name by which he will be called: ‘The Lord is our righteousness.’

Our Jewish friends generally see in that passage a promise of the Messiah who is still to come. We Christians believe the Messianic promise is fulfilled in Our Lord Jesus Christ, the one who, as we heard in today’s gospel, perceived God’s people as being “like sheep without a shepherd”, and in John’s gospel is declared to be “the good shepherd” of all who will come to him. But while we endorse and rejoice in that, it is evident that the coming of the Messiah is not the only thing that our text this morning asks us to have in mind. Between its dramatic opening witness against the shepherds who misled Israel and the final Messianic promise there is another oracle about which I have so far said nothing. According to this oracle, God says that at some time in the future,

I myself will gather the remnant of my flock… 4I will raise up shepherds over them who will shepherd them, and they shall not fear any longer, or be dismayed… says the Lord.

Here, clearly, we aren’t talking about the Messiah. We are talking about various rulers who will arise in the course of Israel’s history. “Don’t worry,” says the prophet, “the bad shepherds may have been greedy and self-interested and made a mess of things, but there will be good people after them, who will do their duty by you. I will see to that.”

This is surely something that many of us need to hear and remember in our distress over the present rule and governance of this nation. A republican political commentator whom I heard yesterday said, “It sometimes seems hard for me to credit, but it is less than two years since we had a president with whose policies I often disagreed, but who never gave me the slightest reason to question his fitness to lead us. We can have such leaders again.” The republican commentator was right.

Let us be candid. This nation has in its short history committed graver sins than it is committing at present, and got itself into worse messes than the mess it is in now. Let us not forget the long history of slavery, longer in this country than in any other western nation, nor the ethnic cleansing of the Native American population (dear God, we of all people should not forget that, for the Trail of Tears passes through our domain!), nor that dreadful Civil War in which 620,000 Americans killed each other.

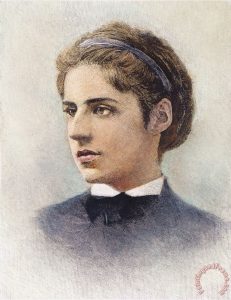

And yet the United States survived those dreadful things, so as to be at other times and in other places genuinely a beacon of hope to the world, so as almost to live up to the words of the American poet Emma Lazarus, now engraved on the pedestal at the base of the Statue of Liberty:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed, to me.[i]

A friend says to me, “At present, when we’re putting children into cages at our border, those words sound to me like a sick joke.” At present, yes, but so perhaps to those who first heard them did the promise of better shepherds in the oracle of Jeremiah sound like a sick joke. The United States has had leaders of all parties who sought to live up to Emma Lazarus’s ideal. It can have such leaders again. We for our part must simply continue to do what ancient Israel had to do, what all honourable men and women everywhere always have to do, that is, our duty: to trust that God remains faithful even when we are unfaithful, and to continue doing our best to make our nation what we believe it ought to be—as President Abraham Lincoln put it, “with malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right.”[ii]

So much for our reading from the Old Testament! Let’s turn now to the passage appointed for our epistle, which comes from the middle of St Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians (and yes, that’s right: despite current critical fashion, it remains in my view far more likely that St Paul was the author of Ephesians than that he wasn’t[iii]). But never mind all that! Let us turn to the text itself.

One of the minor amusements of being an Englishman in America is that from time to time I find myself being treated as an expert on the British Royal family and the Crown—subjects on which I have in fact no expertise whatever. I do, however, occasionally get asked a question I can answer—and one such question is this: what was the significance of the long, decorated rod, and the golden ball, that the Queen was given at her coronation? (One might, I suppose, quibble with the word “given”–after the ceremony was over, the rod and the golden ball went back to the Tower of London, where they are kept together with the crown; but at any rate she got to hold them for a bit!)

“Ah,” I say, “that’s easy.” The “rod”—in this case properly called “the sceptre”—is a symbol of power at least as old as the Bible: it represents power to govern, power to protect. We even heard it in our psalm this morning, when David spoke of the Lord as his shepherd, and the Lord’s “rod” or sceptre that defends him so that he fears no evil even when he is walking “through the valley of shadow of death” (Ps. 23:4). The “ball”—properly called “the orb”—represents the world in which such power is exercised. But if you look closely you will see that there is something rather special about the orb that was presented to the Queen: it has a cross at the top of it. And in the liturgy for the coronation service the Queen was told, “When you see this orb set under the cross, remember that the whole world is subject to the power and empire of Christ our redeemer.”

Precisely.

And that is exactly the point that Paul makes in the opening part of his Letter to the Ephesians, which begins with a glorious vision of the whole created universe in God and in Christ, of ourselves and all things in the midst of what Père Teilhard de Chardin taught us to call le milieu divin—“the divine milieu”— a cosmos in which we find ourselves moving in often bewildering succession through chaos and order, grief and joy, hope and fear, life and death, but always, we believe, toward a goal, a destiny, a fulfilment, which is “to sum up all things”—and Paul very clearly, here as elsewhere, does not say “all Christians” or “all believers” or even “all people”, but quite unambiguously, “all things: τὰ πάντα”—“to sum up all things in Christ, the things in heaven and on earth” (1:10).

Not for Paul the fatuities of human argument—can non-believers be saved? Or, do dogs and cats have souls?—but the constancy of a single fact: the faithfulness of God to the entire creation, faithfulness made manifest in Jesus Christ, risen and ascended and now at God’s right hand,

far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the age to come. (1:20-21a)

Thus the apostle has his eyes fixed on the heavens, the cosmos, the universe, and every creature in it, every man, every woman, every beast, every leaf and blade of grass, all—destined for glory!

But then Paul turns his gaze back to earth, back to the people he is addressing, back to any who will listen, back to us if we will be among them, and speaks to us directly. “And you,” he says: and what we heard read this morning is a part of this direct address. “Remember,” he says,

that at one time you Gentiles by birth, called ‘the uncircumcision’ by those who are called ‘the circumcision’

—and surely here Paul, the former Shammaite Pharisee (as I believe he was), knew exactly what he was talking about! And he follows it with what is surely a recollection of the very assumptions with which he was brought up—“remember,” he says,

that you were at that time separate from [God’s] Messiah, aliens from the commonwealth of Israel, and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world.

There is surely no barrier we can think of, no division we know about, deeper or more profound than that which, for a Shammaite Pharisee, existed at that time between a member of God’s people and a gentile. Let us be clear: that passionate adherence to the Law and circumcision which was so much more a mark of God’s people after the exile than it was before—that is, after they were scattered among the nations, after a situation had arisen in which they might so easily have lost their identity as they could never have done while they were still a sovereign people in their own land—that very passionate adherence to the Law was in some respects precisely so that they might retain their separateness, their distinction as a holy people, a people chosen by God for God’s own possession.

That was how Paul was educated, that was what he once believed, that is what he still remembers. Yet for him—and, he believes, for all who will accept it—everything has now changed. I think I sense him smiling as he dictates—using the very phrase he used in Romans to contrast works of the Law with grace—“νυνὶ δὲ: but now!”

But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he is our peace. In his flesh he has made both groups into one and has broken down the dividing wall of partition, that is, the hostility between us.

“Good fences make good neighbours” we say, and think we are being wise. But if so, it is the wisdom of the world. Oh, perhaps there is a little genuine wisdom in it, while we are still strangers, learning to know one another. But made into an absolute, it is merely one more example of what G. K. Chesterton described as “all the easy speeches that comfort cruel men”[iv]: a convenient excuse to ignore the other, to exclude the other, and then if we will to persecute and oppress the other, on no other ground than that the other is different from us.

Almost the first thing that God says about humanity is that “it is not good for a human being to be alone” (Gen. 2:18). God creates us for fellowship, the divine possibility of union in distinction, the very thing that God’s own Self enjoys in God’s infinite triune perfection. What follows? I think we may safely say that it follows that in the long run God does not like walls, at least not when they are intended to divide.

Paul continues. “God,” he says,

has abolished the law with its commandments and ordinances, so that he might create in himself one new humanity in place of the two, thus making peace…

Of course Paul is not saying that God has abolished Israel’s Law in any absolute sense. In this very letter he does not hesitate to quote that Law more than once (4:7, 25, 26, 5:31, 6:2). He is merely using a little hyperbole to make a point that he makes in another way in the Letter to the Romans—that God’s salvation is “apart from the Law, although the Law and the prophets bear witness to it.” It is with regard to the Law’s functioning in the way that we noted earlier—as a “dividing wall of partition”, as adhered to in order to maintain separateness and distinction—it is in that respect and that respect only that the Law is “abolished”. And again—let us be clear—this is not an attack on the Jewish faith. Alas, any religious tradition can be used in this way: as a wall of partition. Even the doctrine of justification by grace alone can be and sometimes is used as a club with which beat others over the head, a way in which to say, “I believe this and therefore I am different from and better than you.” From which point it is only another step or so to say, “Therefore I am more truly human than you.” But we did not learn such exclusiveness from Christ. Quite the contrary. As Paul points out, “Christ came and proclaimed, ‘Peace to you’, ‘Shalom aleichem’”—that wonderful greeting, often no doubt a thoughtless commonplace in both Hebrew and Arabic, and yet so rich when we think of the meaning it can bear! Christ came

to proclaim, “’Shalom aleichem’, “Peace to you” who were far off, and ‘Shalom’ to those who were near; for through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father.

That is the truth of the gospel, available for all who will have it. “Through Christ we all have access in one Spirit to the Father.” As Wesley said, “’Tis mercy all, immense and free, for O my God, it found out me.” And it is with “the eyes of our hearts enlightened” (Eph. 1:18) by this truth that we are called to look at the world and ourselves.

As many of you know, I am going to England at the end of the month and expect to be there for a year. Which means that I do not know when I shall next preach a Sunday sermon to you: perhaps never! Life is full of uncertainties, and I am not exactly young. Certainly when I am away from the United States what I shall miss most will be my dear friends in Sewanee. But still, as I have long had to remind myself apropos those who are dear to me in England, so at least for the coming year I must remind myself apropos you who are dear to me in America: as the orb of the coronation says, “the whole world is subject to the power and empire of Christ our redeemer”. Which means that whether we are near to each other as the world counts miles or far, still, through Christ we all of us, as Paul says, “have access in one Spirit to the Father.” That is a bond greater than any bond of geography, culture, political allegiance or nation, and it is a bond that no earthly power, and not even the power of death, can break. It is surely enough.

And now let us confess our faith, as the church has taught us…

[i] The American poet Emma Lazarus wrote her sonnet, “The New Colossus” in 1883. She wrote it to sell at an auction to raise money to build the pedestal on which the Statue of Liberty was to be placed in New York Harbour. The statue itself was a gift from the people of France, but American contributors paid for the pedestal. Lines from the sonnet beginning with “Bring me your poor” were later chosen to be inscribed on a bronze plaque that was placed on the platform in 1903. The lines were set to music by Irving Berlin for the musical “Miss Liberty” (1949), based on the story of the sculpting of the statue.

[ii] Abraham Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address” Saturday, March 4, 1865

[iii] As I have pointed out elsewhere, none of the arguments against Pauline authorship is watertight or even particularly strong. Certainly they are not strong enough to merit the current general academic conviction of the existence of an otherwise unknown theological genius who created this magnificent letter (and possibly also Colossians), but left no other record of their existence. The matter was well stated by F. F. Bruce: “If the Epistle to the Ephesians was not written directly by Paul, but by one of his disciples in Paul’s name, then its author was the greatest Paulinist of all time—a disciple who assimilated his master’s thought more thoroughly than anyone else ever did. The man [or woman] who could write Ephesians must have been the apostle’s equal, if not his superior, in mental stature and spiritual insight. For Ephesians is a distinctive work with its own unity of theme… It was no mean judge of literary excellence, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who described Ephesians as ‘the divinest composition of man’ (Table Talk). Not only is it the quintessence of Paulinism, it carries Paul’s teaching forward to a more advanced stage of revelation and application than that represented by the earlier epistles. The author, if he was not Paul himself, has carried the apostle’s thinking to its logical conclusion, beyond the point where the apostle stopped, and has placed the coping-stone on the massive structure of Paul’s teaching. Of such a second Paul early Christian history has no knowledge.” (The Epistle to the Ephesians [London: Pickering and Inglis, 1961] 11-12). Precisely.

[iv] G. K. Chesterton, “Oh God of earth and altar” (in The English Hymnal [London: Oxford University Press, 1906]). For the text online see https://hymnary.org/text/o_god_of_earth_and_altar.