Author: Christopher Bryan

Fr John Crisp

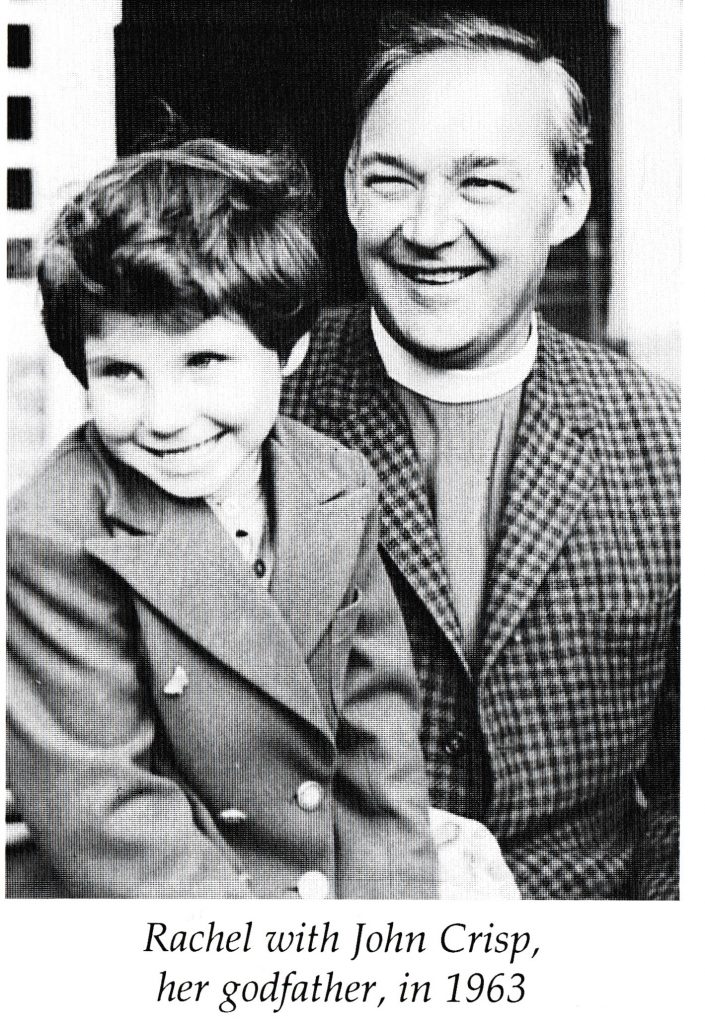

Many people who know me have heard me talk about Father John Crisp, who was my parish priest when I was a teenager at St Mark’s Church, Marylebone Road in the 1950s. And some will have noticed that the statue of Our Lady in the chapel of the School of Theology in Sewanee, Tennessee, is “To the glory of God and in memory of Fr John Crisp”. He was indeed a wonderful priest. I have not the slightest doubt that it is, under God, through Fr Crisp and his influence that I am a Christian, and it is certainly through his influence that I am a priest. During the early part of his ministry at St Mark’s, Fr Crisp’s assistant curate was Father Derek Price, another wonderful priest, with whom, thanks to the efforts of his daughter Rachel, I am again in touch. Rachel has drawn my attention to her father’s beautiful memoir, Choices: After Eighteen (Fakenham, Norfolk: Jim Baldwin, 2011), and in reading it, I was struck by the text of the sermon that Fr Price preached at Fr Crisp’s funeral on 27th October 1989 at St Helens Church in Norwich. (St Helen’s Church is attached to the Great Hospital, where Fr Crisp spent his final years.) The sermon gives a striking impression of the man, and the many ways in which he affected us. I am honoured to be able to republish it here, with Rachel Jackson’s permission.

Sermon preached by Fr Derek Price at the funeral of Fr John Crisp – the Great Hospital Church, Norwich, 27th November, 1989.

Phil. 4.4. Rejoice in the Lord always and again I say rejoice.

- We rejoice at his death

John wanted to die. He prayed that he might die. His body was wretched; it was not the body we had all known, and he longed to be out of it. His prayer was answered. He has been healed through death. So we rejoice. At the same time we express deep gratitude to the staff, the chaplain and the sisters of this ancient hospital for the care of John: for their love, their tenderness and—because John never took kindly to rules and regulations—their tolerance and patience.

- We rejoice in the Lord for John: priest, pastor and evangelist.

When John was interviewed by a bishop for his first living at Saint Mark’s, Marylebone Road, in 1952 he was told that you could only succeed in the London parish if you could develop some specialist line to attract people— such as church music. “What is your trait, your special gift?” he was asked. To which John replied simply, “I have no trait, but I will visit the people.” And visit he did, every afternoon after first taking the telephone off the hook and going to bed for two hours. And this free and this faithful visiting largely contributed to the fact that wherever he served numbers were added to the Lord and the congregations increased.

Regular in the saying of offices and in offering the Eucharist, he was a Catholic-without-lace. But he was also full of evangelical zeal for drawing people to our Lord. He was equally at home with “Sweet sacrament divine”, “Hail Marys” and Mission England with choruses and guitars. Never a diehard, he kept an open mind to worship and liturgy—the giddy days of high mass with incense giving way to the more joyful, relaxed and participatory parish communion. And always there was the short, pithy sermon written in a very large hand—often with mnemonics: S.P.R.I.N.G. for the beginning of Lent! He used to say, “If you can’t enjoy your religion, there’s something wrong with it!” And part of his farewell message at Botley was, “Training disciples as Jesus did, bringing healing to people as Jesus did, sharing their sadnesses and joys, leading them to the heavenly Father in prayer and sacrament! It’s the most wonderful job in the world, being Jesus’ man. I’m thrilled today as I was when I first started off, and never for a moment have I ever been bored.” He certainly enjoyed his religion, and it was infectious.

3. We rejoice in the Lord for John’s vast humanity.

—for his great love of life and laughter. One Bishop of Oxford captured it when he spoke about “that unmistakable voice telling us that John is in the building”! He had a remarkable, boundless zest and energy–even though, all through his life, he was nagged by some pain and suffering. Together with his prayer and his visiting, his obvious humanity was the key to his success in the ministry.

God reveals himself to us through Christ as fully human. His divinity resided in the richness of his humanity. So, we priests and people do not witness to the things of God by having hands always together and eyes always closed, heads in the clouds and angelic otherworldly attitudes and being oh-so-divine. We witness supremely by our uninhibited humanity, by a true worldliness, and by openly enjoying all the good things of God’s creation. Scripture says, “the son of Man came eating and drinking”– and so did John Crisp. He loved food and he loved wine—and O, how he enjoyed those parish holidays that he organised from the beginning to the end of his ministry—yes, even here at St Helen’s, aided and abetted by Michael and Jenny Farthing. Truly he was an ecclesiastical Billy Butlin. He loved to go a-wandering! And he took hundreds of people to see mountains and monasteries, castles and churches, sandy beaches and birds–the list is endless. Small wonder he was able to create such depth of fellowship, togetherness and loyalty in his parishes.

The Roman catholic philosopher Teilhard de Chardin once prayed, “To the full extent of my power, because I am a priest, I wish from now on to be first to become conscious of all that the world loves, pursues and suffers… I want to become more widely human and more nobly of the earth than the earth’s servant.” We rejoice that John was so “widely human” and “nobly of the earth”.

- We rejoice in the Lord for John’s enormous capacity for making friends with all sorts and conditions of men and women.

—with the rich man in his castle and the poor man at his gate. Though being a life-long socialist, he would remind the rich man to share some of his good things with the poor, for he had a very special place in his heart for the involved, the downtrodden and deprived. Significantly enough, he wanted—and therefore he got—a chapel at St Mark’s dedicated to St Francis of Assissi.

I suppose I was one of the first to come under the inspirational spell of his friendship, consenting to become his first curate without seeing the church, the parish, the people or enquiring about pay or a place to live. I went simply because I knew John. That was enough. I never regretted it. Two days before his death I read him a letter from a friend. It recalled with delight walks with John around Newport Pagnell, meals shared; but above all the writer thanked him for encouraging and helping him to become a lay reader. Typical of John’s influence on people!

John would go off to do a chaplaincy in Switzerland, meet up with some Major General or other, and before the end of the fortnight the latter had promised to pay for a new vestry or contribute to one of John’s many imaginative schemes for transforming or beautifying his churches or halls. How did he do it? John had no favourites. He reflected a God who is not a respecter of persons. Like the prophets of old he would fiercely rebuke those in high places if need be, huffing and puffing and chewing his hanky as he approached the unwelcome task. He was equally hard-hitting in parish-magazine letters if he wanted to be—especially on the subject of politics, poverty or peace. His opponents may have found him infuriating, but I suspect they still admired him.

- Finally, though so much more could be said, we rejoice that John reached the Biblical three-score years and ten

—thanks to a lot of overtime put in by St Christopher and a tireless squad of guardian angels! In driving hazardously in various vehicles from A to B Mr Toad had nothing whatever on Father Crisp! Milk-floats, plate-glass windows, lampposts—you name it, he ran into it! His last attempt was to ride a tricycle. Mercifully, he didn’t succeed, managing only to go round and round in everlasting circles, never in a straight line.

“Rejoice in the lord always, and again I say, rejoice.”

“John,” wrote a parishioner from Botley in a retirement tribute, “has been amongst us as a sign and a saint. An inspiring, loveable, exasperating, prayerful, challenging man of God.”

As we commit his soul to the Love and Mercy of his Heavenly Father and to that peace for which he strived ceaselessly throughout his life, I say on behalf of countless friends,

“Thank you, John, for enriching our lives.” Amen.

Things We Can Get Wrong about Scripture: notes for a sermon at St Olave’s, Exeter.

Epiphany 3. For the OT Nehemiah 8.1-3, 5-6, 8-10; for the Psalm 19; for the Gospel Luke 4.14-21

Our readings today continue the Epiphany theme—that is, the theme of Manifestation, of God’s self-revelation. Three things one quite often hears said about Christian revelation. Two are defending it.

The first is this: “Christian revelation is through the Bible and only through the Bible.” The Latin tag “sola scriptura”—“Scripture alone”— is often quoted here.

The second is: “Bible teaching is plain and straightforward, and we should just do what it says.”

The third saying is actually anti-Christian, and it’s this: “Jesus can’t have been the promised Messiah of Israel, because the promised age of peace and joy that he promised has not come about.”

The three statements have one thing in common, and it’s this. They are all wrong. Or, to be more precise, they are all based on mistaken assumptions. And as it happens, our three readings this morning each contradicts one of them.

First, that “Christian revelation is through the Bible, and only through the Bible.” The Bible itself tells us that this isn’t true—and nowhere more clearly than in the magnificent opening to this morning’s psalm that we just read together—Psalm 19. What does the psalmist say?

The heavens are telling the glory of God ♦

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

(Ps. 19.1)

—wonderfully paraphrased by Joseph Addison in a hymn I used to enjoy singing when I was at school—#267 in the New English Hymnal! Perhaps some of you remember it:

The spacious firmament on high

With all the blue Ethereal Sky,

And spangled Heav’ns, a Shining Frame,

Their great Original proclaim…

And utter forth a glorious Voice,

For ever singing, as they shine,

The Hand that made us is Divine.

What then is meant by the tag “sola scriptura”—“Scripture alone”? What those who formulated that phrase were saying was that Scripture alone gives us all that is necessary for our salvation: in particular the saving truths of our Lord’s life, death and resurrection. But God in Divine generosity always offers us more than merely what is necessary. God gives us what the ancients called copia—abundance and superabundance, overflowing, and if only we will pay attention the Divine calls to us in the whole created order. The Psalmist and Addison pointed to the heavens. Dante saw it in a girl’s smile. Someone else sees it in a flower, or in hearing a piece of music—but we could go on for ever—and one day, please God, we will.

Second, some people will tell us that, “Bible teaching is plain and straightforward, and we should just do what it says.” Well—is it? In some ways this assertion is more dangerous that the last one, because it contains a half-truth. Certainly there are some elements in Scripture that are plain and straightforward. Most obviously, all Scripture presents us with a view of reality that says our lives and all lives are based in the one God, who is faithful and just: according to Scripture, if we insist on any other view, we are rebels against the truth. I suppose Scripture is pretty clear about how we should live those lives, too. “Love the LORD you God” and “Love your neighbour as yourself” is said or implied almost everywhere. The two are expanded a little and run together in the prophet Micah’s beautiful,

“He has shown you… what is good: and what does the LORD require of you but to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6.8)

But there are also many things in Scripture that are not at all plain and straightforward. An uncle of mine used to say, “You can prove anything and everything from the Bible”, and although I think he exaggerated, he had a point. What, after all, should be the people of God’s attitude to those who are not members? If you read God’s promise to Abraham in Genesis and then Moses’ command to the Israelites as they enter the promised land, you could be forgiven for thinking they imply completely opposite things. SO, how shall you decide what are you to believe, or perhaps more importantly in this particular case, what to do? How are you to treat outsiders to the Christian faith?

That’s where our second reading comes in, from Nehemiah. It’s a dramatic scene: some people call it “the founding of Judaism”. The people have returned from exile in Babylon, and in an act of repentance and dedication after their past failing, they listen publicly to the entire “book of the Law”—I imagine we should take it to mean what we call the Pentateuch—the five books of Moses—being read from early morning to midday. It must have been quite an endurance test. But there’s something else about them. They were read to, says Nehemiah, “with interpretation”—“מְפֹרָשׁ” as the Hebrew has it—and goes on to explain what this means: “and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading”. In other words, Nehemiah reminds us that although the basic ideas of Scripture may be clear, there’s much about it that is difficult and or confusing. Scripture needs interpretation. And incidentally, lest there be any doubt, apropos the particular question I just instanced–how are we to treat outsiders?–I’d say that it becomes pretty clear on careful reading of Scripture as a whole that the dominant message is not so much to worry about “Who is my neighbour?” as to consider how I can be a neighbour to anyone who comes into my life–as Our Lord reminded the lawyer who asked this very question, and received for an answer the story of the Good Samaritan.

What then of our third frequently heard saying—the anti-Christian one: “Jesus can’t have been the promised Messiah if Israel, because the promised age of peace and joy has not come about.”

This always reminds me of a time I was feeling very sorry for myself: you know, one of those days when you feel God has completely let you down, even though you’ve been a really good chap, and you wonder why you bother. I was driving, as it happened, and without thinking about it much I switched on the car radio. And what did I did hear? The great Lyn Anderson: “I beg your pardon, I never promised you a rose garden.”

And, of course, God didn’t and Jesus didn’t. Certainly we are promised that finally we shall know the fullness of joy: but our Lord himself did not come to that joy except through the gate and grave of death, and his promise to us is NOT for an immediate era of peace. Quite the contrary. “In the world,” he tells us, according to the fourth evangelist. “You will have tribulation”—adding only “but be of good cheer, I have overcome the world.”

And so this morning’s gospel passage. Our Lord reads from the Scripture and declares, “This Scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.” But what is that scripture? Is it a promise of perfect peace and immediate happiness for all? By no means: it is a promise of signs by which we may know that God is at work even in the midst of darkness, even in the valley of shadow:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.”

That is what Jesus did, that is what men and women experienced in him, that is what was vindicated in his resurrection from the dead, and for that the Spirit of God was given to the church. Alas, the church, as we know only too well, has not always been and is not always faithful to that vision, and neither, of course, are we as individual Christians. Yet that is what the church and we as individuals stand for when we are true to Christ. No, we are not promised a rose garden. We are not promised–yet–the messianic kingdom in its perfection. But we are given the upward call of God in Christ Jesus, and the promise that not one single effort we make to be faithful to that call, not one single tear we shed for the sake of it, shall be lost or wasted. As our Lord himself said on one occasion:

“Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground unperceived by your Father. And even the hairs of your head are all counted. So do not be afraid; you are of more value than many sparrows.” (Matt. 10.29-31)

The Armour of God. For St Olave’s, Exeter. Proper 16b, 2021

The Armour of God. For Exeter Central Parishes (13th after Pentecost 2021).

The parish has been reflecting in previous weeks on the lectionary readings from the Letter to the Ephesians, which is in its form perhaps originally a circular (or even, “encyclical”) rather than a letter to a particular individual or community, designed to be sent not only to Ephesus but to the other Ephesian churches. In terms of rhetoric it is an example of what rhetoricians contemporary with Paul would have called “panegyric”—that is, speech in praise of something. Ephesians, of course, is particularly concerned to praise God: more precisely, to praise what God has done and is doing for God’s people through Jesus Christ—the implications of which, however, go far beyond God’s people—whether by that expression we mean “Israel” or “the Christian Church”. From its very beginning, Ephesians makes clear that the redemption which God is bringing about is cosmic in its scope. Hence it is the true hope of the entire created order, for it is God’s will “to sum up all things in Christ, the things on heaven and the things on earth” (Eph. 1.10b).

Such faith and hope, declared in the opening verses of Ephesians, are the basis on which the rest of Ephesians builds, including 6.10-20, the famous “whole armour of God” passage, which is our particular reading for this Sunday.

We may conveniently divide our passage into three parts:

I. Finally, be strong in the Lord and in the strength of his power. Put on the whole armour of God, so that you may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil. For our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.

The Ephesians are to place their trust in nothing less than the power of God, and nothing less than the power of God is what they need, for the evil that opposes them in life is more than merely human. In Paul’s view—and it is the biblical view—humankind is not alone in being rebellious against God and God’s grace. There are in the universe other “cosmic powers of this present darkness” that are in rebellion against God, and they will overcome us if they can.

For some moderns, such ideas are to be equated with old-fashioned pictures of devils with a horn and a tail, being simply too crude and unscientific to be be taken seriously. Others, contemplating the monstrous evils that have been perpetrated throughout history, apparently through human agency and not infrequently even in the name of religion, may well ask whether there is not indeed at work here a malignancy greater than can be explained by merely human evil: a malignancy that can lead the same humankind that produces a Saint Francis and a Mother Theresa, an Albert Schweitzer and a Florence Nightingale, to produce also the horrors of Auschwitz and and Hiroshima.

Whatever our opinions as regards that debate, and however we choose to characterise evil or its origin, it is beyond doubt that life and history confront us with much that is evil, and in our own strength we may well feel unable to stand before it. Paul, however, declares that God has provided us with a refuge in our plight. The prophet Isaiah, centuries before Paul, had used the metaphor of God’s armour. Seeing the world’s injustice, Isaiah said, God acted:

He put on righteousness like a breastplate,

and a helmet of salvation on his head

(Isa. 59.17)

Such armour, Paul declares to the Ephesians, will also be God’s gift to them if they choose to take it, and will enable them to stand against their enemy.

II. Therefore take up the whole armour of God, so that you may be able to withstand on that evil day, and having done everything, to stand firm. Stand therefore, and fasten the belt of truth around your waist, and put on the breastplate of righteousness. As shoes for your feet put on whatever will make you ready to proclaim the gospel of peace. With all of these, take the shield of faith, with which you will be able to quench all the flaming arrows of the evil one. Take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.

Pursuing the metaphor, Paul goes on to list six elements in this armour, modelled no doubt on the weapons and armour of a Roman legionary in his own day, and gives to each element a metaphorical sense.

- Belt: this most likely refers to a leather apron that was worn by legionaries both for protection and to allow freedom of movement. Paul, however, associates it with “truth (alētheia)”. The essential thing implied by the word “truth” as Paul and his audience will have understood it was not (as perhaps with us) something that was accurate, but rather something that may be relied on—as when we speak of a friend who is “true”—someone you can trust, someone who is faithful. So whose “truth” is Paul talking about? This is God’s armour, and so of course it is God’s truth and God’s reliability that are here in mind. God is true, Paul says, and that truth, if we take it to ourselves, will serve both for our protection and as our only firm basis for action.

The Roman soldier’s “belt” was also used to secure the next item of his equipment, which was the

2. Breastplate: the Greek word here is thōrax, which is used at different periods to refer to virtually anything that protects the chest. Again, Paul probably had in mind the standard equipment of a Roman legionary. The metaphorical thōrax of which he speaks is, however, God’s “righteousness (dikaiosunē)”. The word “dikaiosunē / righteousness” means not “virtue” (as we tend to understand it) but rather loyalty and faithfulness. God is faithful and loyal towards us: and that faithfulness and loyalty mean that God will stick by us even though we are sinners, which indeed we all are (Rom. 3.23, 11.32). This “righteousness”, together with the “truth” of which we previously spoke, are the basis of the “armour” that God gives us.

3. Shoes: Paul perhaps has in mind here the heavy boots (caliga) of a Roman legionary. These gave strength for long marches and for standing firm in battle. The gospel was above all “the good news of peace”—peace between God and humankind. Such was the message of the angels to the shepherds at the birth of Christ (Luke 1.14). And the knowledge of such peace is the footwear in which believers may indeed hope to stand firm, despite their personal weakness and failings.

4. Shield: the Greek word is thurios, derived from the word for “door”. It describes a large, door shaped shield: in other words, Paul is evidently thinking of the heavy square shield (Latin: scutum) carried by a Roman legionary of the period, which was effective both defensively against missiles and offensively when a detachment of legionaries might advance with shields side by side and a cover of shields above their heads. For Paul the Christian’s shield is “faith”—God’s faithfulness to us, inviting our faith in return: a shield with which the Christian may indeed “be able to quench all the flaming arrows of the evil one”.

5. Helmet: Paul is probably picturing the helmet with cheek pieces of a Roman legionary. But this helmet is “of salvation (sōtērios)”—that is, of “deliverance”: God’s deliverance from what oppresses us, whether it be sin or, finally, death itself.

6. Sword: the legionary, of course, carried a sword: short and straight. Paul, however, speaks of “the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God”. The writer to the Hebrews also associates God’s word with a blade, speaking of it as “quick, and powerful, and sharper than any two edged sword, piercing even to the dividing asunder of soul and spirit, and of the joints and marrow, … a discerner of the thoughts and intents of the heart” (Heb. 4.12). Here in Ephesians Paul speaks of God’s Word as “the sword of the Spirit”. “Spirit” (Hebrew ruach, Greek pneuma: both meaning “breath” or “wind”) is a word that the Bible uses frequently to speak of God’s living, creative, dynamic power—God’s “breath”—working in and through humankind and the created order. So, for example, Isaiah looks for “the Spirit of the LORD” to rest on Israel’s ideal king (Isa. 11.11-2: for other examples of God’s creative “breath” bringing order out of chaos or life out of death cf. Gen. 1.2-5, Ezek. 37.1-14). Paul evidently identifies our prayers as one such of work of the Spirit, and in particular that prayer in which the Spirit prays with us (Rom. 8.26-27). It is that kind of prayer—prayer “in the Spirit”—about which he will now go on to speak.

III. Pray in the Spirit at all times in every prayer and supplication. To that end keep alert and always persevere in supplication for all the saints. Pray also for me, so that when I speak, a message may be given to me to make known with boldness the mystery of the gospel, for which I am an ambassador in chains. Pray that I may declare it boldly, as I must speak.

As the Ephesians seek to take to themselves God’s faithfulness and grace as their armour and shield, so they are asked to pray “in the Spirit”—that is, in the power of God that lives in them and breathes through them in virtue of their baptism. They are to offer prayer for all, but especially for their fellow Christians and for Paul himself. Evidently in prison, Paul does not hesitate to refer to his own personal situation. He does not, however, ask the Ephesians to pray for his release or even his safety, but that he may speak with “boldness”—the Greek word is parrēsia, a word that is used in Acts to describe the way in which apostles freely and bravely give their testimony (e.g. Acts 2.29, 4.29, 31).

What Paul must speak about is the “mystery of the gospel”—that is, the truth about God’s love and grace that was hidden in past ages but has finally and definitively been shown to us in Jesus Christ—the “mystery” of God’s eternal purpose “to sum up all things in Christ” with which his homily began. On behalf of this “mystery”, Paul says, he himself is “an ambassador in chains”—a wonderful expression in which he expresses at once his sense that he has been empowered by God to speak the truth of God’s grace, and also that his “chains” are not things that make him bitter or angry, but rather the signs and pledges of his office as ambassador—that is, as representative, as qualified plenipotentiary—on behalf of the One who Himself, “did not think equality with God” was something to be exploited, but “humbled himself, being found in fashion as a man”—and so shared the common human lot “even in unto death” (Philip. 2.6, 8).

We may surely ask for nothing less than the same endurance for ourselves and our communities as we seek in our own time and place to be faithful to God and God’s world. And what is that time and place? Many things, no doubt, for many people. God does not create two snowflakes alike, let alone two human lives. Yet we also have things in common. Our own Bishop Robert, in his July 2021 ad clerum letter, quotes words of St Cyprian of Carthage about these things we have in common, and I can think of no better way to end these notes than by quoting them too. In third century Carthage in North Africa there was a virulent outbreak of plague. Cyprian the bishop, reflecting on its impact, wrote:

Some talk as if being a Christian guarantees the enjoyment of happiness in this world and immunity from contact with illness, rather than preparing us to endure adversity in the faith that our full happiness is reserved for the future. It troubles some that death has no favourites. And yet what is there in this world that is not common to all? Diseases of the eye, attacks of fever, weakness in limbs, are as common to Christians as to anyone else because they are the lot of all who bear human flesh. What distinguishes the righteous should be our capacity for endurance. (On the Mortality Rate, 8, 11-13)

Bishop Robert comments, “This is God’s world and God invites us to build communities of grace that speak of hope.” The Letter to the Ephesians teaches us to do precisely that. To which teaching we must surely say, “Amen!”

David and Bathsheba: a story for our time

Proper 12 B: 2 Samuel 11.1-15.

One reason I love the Scriptures is that they never duck away from the fact that there’s real evil in the world, including in those whom we think of as the best and the brightest. And that thought brings me to our reading for this morning. It’s a story about King David, who is generally regarded as a hero. We all the know the tale of him slaying the mighty warrior Goliath—a classic tale of the underdog pulling it off, the weak outwitting the powerful. David goes on to become in tradition Israel’s greatest ruler. Centuries later, Matthew in his gospel, in what are actually the opening words of the entire New Testament, will call Jesus “son of David”— that is, a true heir to the royalty of Israel, the ideal king—even before he calls him “son of Abraham”—that is, a true Israelite, a true Jew. (Jesus himself, to be sure, raised questions about the appropriateness of calling God’s Messiah “son of David”—see Mark 12.35-27— but that’s another story.) So David is a hero. But David is certainly not a perfect human being, not even close, and the Bible makes no bones about that, either.

In our Old Testament reading for last week, we heard about God’s promise to David. It began with David settled and secure in his kingship, but aware of the irony that “I live in a house of cedar, but the ark of God stays in a tent” (2 Sam. 7.2). Therefore David proposed to build “a house” for the LORD—that is, a temple. At first Nathan the prophet approved of this

“Nathan said to the king, ‘Go, do all that you have in mind; for the LORD is with you.’” (7.3).

But that night God’s word came to Nathan, and he was sent back to David with a very different message of which the heart was this: David had proposed to build a “house” for God. That was not going to happen—for two reasons. First, because God hadn’t asked for it (7.6-7) and second, because it was God (not, by implication, David) who would uphold both David and God’s people. What was going to happen was this: that God would build a “house” for David (2 Sam. 7.11).

“When your days are fulfilled and you lie down with your ancestors, I will raise up your offspring after you, who shall come forth from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. He shall build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom for ever. I will be a father to him, and he shall be a son to me.” (2 Sam. 7.12-14a)

Here was an extraordinary promise. God has made a commitment to the family of David that is much like God’s commitment to Israel: which is to say, the family of David will never be forgotten or forsaken by God. That doesn’t mean, of course, that individual members of the family can do what they like. Like Israel itself, the Davidic king is still subject to God’s laws. Nowhere is it suggested that he may ignore the commandments given at Sinai. On the contrary, when individual kings ignore God’s justice and commit iniquity, in other words, when they screw up, they will be punished—even David himself. So God’s word of promise concludes with a solemn and no doubt necessary warning:

“When he commits iniquity, I will punish him with a rod such as mortals use, with blows inflicted by human beings.” (7.14b)

Nevertheless, come what may, God will remain faithful to the house of David:

“I will not take my steadfast love from him, as I took it from Saul, whom I put away from before you. Your house and your kingdom shall be made sure for ever before me; your throne shall be established for ever.” (7.15-16)

Now if you are reading this note with last Sunday’s lectionary reading in front of you, you will notice that I have actually gone beyond the place where the reading stopped. These last words, the words of warning, were omitted, so that our reading ended simply with the promise, “I will be a father to him, and he shall be a son to me”—without the warning. We may well wonder, Why? It can hardly be an accident. Our compilers actually had to end the reading in the middle of a verse in order to achieve it, so they surely meant it. Was it a policy to shield us from the thought that David would ever do anything wrong? If so, it was sadly mistaken, because David DOES do something wrong, and big time. And we hear about it in the reading for this Sunday.

David and Bathsheba! It’s a story that’s been romanticised over time into a great love story: and the classic 1957 film David and Bathsheba, with Rita Hayworth and Gregory Peck in the title roles, played right along with that. But the Bible is much blunter than Hollywood, and we can forget all about “romance” if we are going to be faithful to the actual Biblical story as we hear it told this morning.

It begins, says the writer of 2 Samuel, “In the spring of the year” (11.1a). Well, that sounds romantic enough doesn’t it? Stagione d’amore—the season of love. “Sweet lovers love the Spring”—that’s what Shakespeare said, isn’t it? No wonder David and Bathsheba fell in love! Who can blame them?

But “seasons of love” aren’t what our author is talking about, as he at once makes clear. “In the spring of the year,” he says, “the time when kings go out to battle”— that’s what he is talking about. In the ancient world springtime, with the whole summer ahead, was the obvious time for a king who had military targets in view to begin a campaign. And David has several such targets: the Ammonites need subduing, and so does the city of Rabbah. Except that David, now that he is the great king in Jerusalem, with absolute power, and the beloved of God, no longer has to see to such things himself.

“David sent Joab with his officers and all Israel with him; they ravaged the Ammonites, and besieged Rabbah. But David remained at Jerusalem.” (11.1b)

Does David then stay at home because he’s burdened with affairs of state? Apparently not, or not too much. One surely is right to hear a note of irony in our author’s voice as he continues, “It happened, late one afternoon, when David rose from his couch”—a lengthy siesta! That, it appears, is the “affair of state” that’s been occupying David the king today. And now he takes a stroll, “and walking about on the roof of the king’s house, it happened that he saw from the roof a woman bathing; the woman was very beautiful” (11.2).

What happens then? A lot! We notice that in every significant verb that follows it is David—strong, powerful, secure David—who is the doer, the mover, the actor, the shaker, no one else. And what is it he does? First—

“David sent someone to inquire about the woman. It was reported, ‘This is Bathsheba daughter of Eliam, the wife of Uriah the Hittite.’” (11.3)

Uriah the Hittite is a soldier in Israel’s army, fighting Israel’s battles. And he isn’t just any soldier. We read elsewhere that he is actually one of David’s elite—“the Thirty”—the most trusted and valiant (2 Sam. 23.39). So what does David do? He’s a man of action still, just as he was in the days when he led a tiny warrior band against heavy odds—except that now it’s all for himself: which brings us to the next significant verbs:

“So David sent messengers and took her (וַיִּקָּחֶהָ). And she came to him and he lay with her.” (11.4a)

And that’s it. To call it “stark” is almost an understatement. There’s no conversation. No hint even of mutual attraction. David is Mr Big, and what Mr Big wants he takes. This is not romance It’s not even illicit romance like in the Rita Hayworth and Gregory Peck movie. It’s just lust: “the expense of spirit in a waste of shame” as Shakespeare put it.

“Then she returned to her house.” (11.4c)

Well, of course she does. When it’s over, the girl can be sent home. Job done. Mission accomplished: “before, a joy proposed; behind, a dream”—just as Shakespeare said. All is under control.

But there are some things even Mr Big can’t control. There was a warning note, actually, and our storyteller mentioned it, although David was at the time too full of what he wanted (the “joy proposed”) to consider it. The warning note was, “now she was purifying herself after her period” (11.4b). Of course the ancients knew just as well as we do that that was the time when intercourse was most likely to lead to conception.

So now we finally get three verbs of which the woman is very clearly the subject:

“The woman conceived. And she sent, and she told David, ‘I’m pregnant.’” (11.5)

Now that’s a problem. That’s something not even Mr Big can control.

But David is still the man of action, and he acts swiftly:

“So David sent word to Joab, ‘Send me Uriah the Hittite.’ And Joab sent Uriah to David. When Uriah came to him, David asked how Joab and the people fared, and how the war was going.” (11.6-7)

Prettily he plays the good commander, interested in the welfare of his troops!

“Then David said to Uriah, ‘Go down to your house, and wash your feet.’” (11.8a)

—an expression almost certainly carrying a sexual innuendo. So—

“Uriah went out of the king’s house, and there followed him a present from the king.” (11.8b)

All will be well. Uriah will sleep with Bathsheba. No one will know whose the baby it is, since fortunately we haven’t yet invented DNA testing, and David will be off the hook.

“But Uriah slept at the entrance of the king’s house with all the servants of his lord, and did not go down to his house.” (11.9)

That was something David hadn’t bargained for.

When they told David, “Uriah did not go down to his house” David said to Uriah, “You have just come from a journey. Why did you not go down to your house?” Uriah said to David, “The ark and Israel and Judah remain in booths; and my lord Joab and the servants of my lord are camping in the open field; shall I then go to my house, to eat and to drink, and to lie with my wife? As you live, and as your soul lives, I will not do such a thing.”

That ought to have struck David to the heart! And the fact that it doesn’t shows just how much he has changed from the man we heard about last week in 2 Samuel 7—the man who wanted to build a Temple for the God of Israel! Do you remember what David said then?—almost exactly what Uriah is saying now. “See now,” he said, “I’m living in a house of cedar, but the ark of God stays in a tent”—that seemed to him a terrible thing. But that was then. And this is now. And now it’s only loyal Uriah who thinks like that. David now seems quite happy not only to be in his house of cedar while the Ark is in the fields of battle, he’s also happy to take a the wife of another man while he’s doing it, and that a man to whom he is bound by vows of fealty and honour as his liege lord.

But David isn’t yet out of options.

“Then David said to Uriah, ‘Remain here today also, and tomorrow I will send you back.’ So Uriah remained in Jerusalem that day. On the next day, David invited him to eat and drink in his presence and made him drunk.” (11.12-13a)

Surely Uriah will be unable now to resist the thought of going in to his beautiful wife? But Uriah is dutiful, drunk or sober—

“and in the evening he went out to lie on his couch with the servants of his lord, but he did not go down to his house.” (11.13b)

We assume David’s spies tell him this. And now, surely, he is out of options? Well, he isn’t. He has one more card to play, and none of the trivial considerations that might cause lesser men to hesitate—such as loyalty or decency or God’s prohibition of murder—are going to stop him from playing it.

“In the morning David wrote a letter to Joab, and sent it by the hand of Uriah. In the letter he wrote, ‘Set Uriah in the forefront of the hardest fighting, and then draw back from him, so that he may be struck down and die.’” (11.14-15)

It’s a death warrant. This is something of a pivotal moment in 2 Samuel. David has gone from hero to villain, from defender of his people to oppressor, from king to tyrant. He’s become exactly the king about whom the prophet Samuel warned when he counselled Israel against having a king at all: a king who “will take [יִקָּח]” whatever he wants (1 Sam. 8.11-17). And God help anyone who even unwittingly stands in his way.

At this point the reading appointed for us by the lectionary ends—as it seems to me, in the middle of the story. Perhaps that’s because the lectionary compliers wished to spare us the full implications of what David had done? I don’t know. At any rate, I do know that the author of 2 Samuel had no such scruples, and since our loyalty to holy Scripture must exceed even our loyalty to the framers the lectionary, neither will I.

Briefly, what follows is that Joab, obedient hatchet man that he is, gets the job done. He orchestrates a deliberately foolish military manoeuvre that leaves Uriah exposed and vulnerable, and Uriah is killed, along with several other of David’s servants—other faithful soldiers who are also doing their duty by their king. So Bathsheba isn’t the only woman in Israel who is left a widow by that day’s work. But what of it? David’s secret is safe. “Let not this thing displease you,” is his word to his hatchet man when the news arrives (11.25a). What would it matter if an entire platoon were lost? David’s image has been preserved. “The sword devours now one and now another,” he tells Joab by way of comfort (11.25b). And of course that’s true. War is like that.

But this wasn’t war, was it? It was murder.

The widowed Bathsheba is allowed the seven brief days’ of mourning for her husband that are customary. Then without further delay or preamble, “David sent and took her to his house and she became his wife” (11.27). The Hebrew is blunt, even abrupt: “וַיִּשְׁלַח דָּוִד וַיַּאַסְפָהּ”. We might even translate, “he sent and collected her”—she’s property, previous owner deceased, therefore assigned to the crown. That’s the brutal fact.

I began these notes by saying that one reason I value the Scriptures is because they face the fact that there’s evil in the world. David in this morning’s reading is one with every tyrant and dictator there’s ever been.“Power tends to corrupt,” wrote Lord Acton, “and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” If the author of 2 Samuel hears those words now in heaven, he surely nods and says, “Yes. That’s just what I was saying!”

The American writer Robert Stone during his brief days in Vietnam during the Vietnam War became aware of an expression repeatedly used as people talked about the latest element in the horror and devastation that surrounded them. In time they’d come to a point in the conversation where nothing more could be said. So they simply said, “There it is.”, and stopped. But what was the “it”? Thomas Powers suggests “it” was “The thing about which nothing can be done.” I think Powers is right. And people like the person David has become are the ones who give that “nothing” its power. And they don’t even mean to do it. They intend nothing more than to get whatever they want, or to achieve whatever they think should be achieved. And they simply don’t have time to concern themselves about who or what might be hurt in the process.

Stone, of course, wrote about a universe from which (in his view) God was notably absent. The author of 2 Samuel does not. “Let not this thing displease you!” says David to Job. He clearly intends it to be the last word. “Press your attack on the city and overthrow it,” he adds (11.25). In other words, “There are more important things to worry about than the death of Uriah the Hittite. All that’s water under the bridge.” Our author, however, has a different word: “the thing that David had done displeased the LORD.” That’s all. It’s only a hint. It doesn’t mean that the LORD will intervene directly at this point in the story. But then, the LORD won’t intervene directly even when Jesus the son of God hangs dying upon the cross. The LORD won’t intervene at Auschwitz or Hiroshima or any of the other countless acts of brutality and horror that litter human history. What the hint does mean, however, is that what we have just heard is neither the end of the story nor all that there is to say about it (even though the Davids of this world would like it to be). Our author himself will go on to describe a prophetic confrontation over the affair between David and God’s prophet Nathan. We shall hear about that in our Old Testament reading next week, in what’s surely one of the most powerful pieces of dramatic prose ever written (12.1-25). In the mean time, “The thing that David had done displeased the LORD”. So, yes, there is more to say and no, death will not have the last word. But death has been allowed a word—cold, cynical, worldly wise and brutal—and that, for what it is worth, is what we have just heard.

AMDG: Sermon at the Ordination to the Diaconate of Pamela Morgan, in Little Rock, Arkansas: 22nd February 2001.

Let me begin by saying how honoured I am to be with you on this wonderful occasion, and how grateful I am to Pamela for inviting me to share with you all as she commits herself to this new stage in her life and ministry.

Since this is an occasion of commitment, I should like, if I may, to reflect with you for a few moments on that very subject: on Christian commitment – both what it is, and what it is not. Part of my reason for this is that we seem to be hearing a great deal these days from a certain style of preacher about the need for Christian commitment, and church’s lack of it. Indeed, sometimes I wonder what it all means. To judge by some of this preaching, it almost seems that I’m to understand there are two sorts of Christians – ordinary Christians and committed Christians, and we need to make sure we’re the right sort.

But how are we to know we’re the right sort? Will it be evident from the set of our jaws, or the slightly glazed look in our eyes? What is the difference between ordinary Christians and committed Christians?

Now there is one level, of course, on which the question can be answered very simply. If we mean that there’s a difference between committed Christians and people who merely play at religion – who, for example, toy with the possibility of joining the church without ever actually getting baptised or confirmed, or who like on some occasions to enjoy what people used to call “the consolations” of religion yet jeer at religion when with they’re with their sophisticated atheist friends, or else reject the authority of religion when its demands inconvenience them – if, in other words, if we mean that committed Christians can’t be people who try simultaneously to run with the fox and hunt with the hounds – why then, I think we must agree. What’s more, I think we must say that people who do try to live in such a way are playing a very dangerous game indeed, with themselves if with no one else. And one day, in some way, the dangers will very likely catch up with them. But surely all that is so self-evident as to be hardly worth saying? Surely the preachers who call for “committed” Christians must be saying something slightly less obvious than that?

Yes, I think they are. I think what they are actually doing is offering a subtle (or perhaps not-so-subtle) criticism of the church simply for being what it is: a company of sinners – redeemed sinners, of course, but sinners nonetheless. I seldom hear such preachers quoting Luther – that the Christian is simul iustus et peccator – “at once justified and a sinner” – and I often hear them quoting (it must be confessed, somewhat out of context) what John the Seer said about the church in Laodicea being “lukewarm, neither cold nor hot,” and then applying it to the rather feeble, run-of-the-mill church as we ourselves know it – and needless to say, that means the Episcopal church in particular. “This church, too, is lukewarm,” they say. “It is, after all, so full of hypocrites. So full of people who don’t live up to their profession! So full of squabbles even about what Christian profession means, or how to live!” You know the sort of thing, and doubtless you’ve heard it a thousand times, as I have. Sometimes they will even say, “What we need is a spot of persecution. That would soon sort out the real Christians, the committed Christians, from the others.”

There is a sense, of course, in which all that they say is completely true, and has been true from the twelve disciples onwards, every one of whom betrayed Jesus and fled, when the chips were down; and who were squabbling among themselves about what it meant to be a follower of Jesus from the very beginning. Read Mark ten, thirty-five to forty-five, or the fifteenth chapter of the Book of Acts, or the Letters of Paul to the Galatians or the Corinthians, if you don’t believe me.

What is not true, however, is the conclusion that some of these preachers want us to draw from all this, which is, first, that “committed” Christians ought therefore to go off and form some nobler, holier, more truly committed group than such an average, run-of-the-mill church as ours; and second, that what is demanded from us if we are to be “committed” Christians is a commitment to Christ that is perfect, irrevocable, and complete.

To all that I have a response of my own, which is that both those conclusions involve monstrous self-deception.

First – what is this group to be like, that will have ideals so much nobler than that of the run of the mill church? I am reminded of the young man in the gospels who came full of vision to Jesus, asking what he should do to find salvation. Simply, kindly, Jesus reminded him of the commandments, which, of course, everyone knew. “Oh, that old stuff! How boring! I’ve done all those since I was so high!” said the young man – and Jesus looking on him loved him. And what else can you do with someone who has the gall to claim that he’s mastered all the commandments except love him?

So then, what of this ordinary, run-of-the-mill Episcopal Church to which we all belong? What does it offer, and to what end? It offers the Word of Jesus to our hearts and it offers the Body and Blood of Jesus to our mouths, to the end that we may go and be Jesus among the people with whom we find ourselves. Quite simple, really – and will anyone who has managed it please see me after the service. If you have managed all that, then we can talk about finer, nobler, holier groups to which you might choose to belong.

What then of the second claim – that what we need is real commitment, a commitment from which we will never go back, never deviate?

I reply, quite simply, that for us, all of us, such a commitment is impossible, and to imagine we had made it would therefore simply be a piece of self-deception.

Why is it impossible? It is impossible because you cannot cross a bridge before you have reached it and you cannot fight a battle before your enemy has taken the field.

You promise chastity, and you mean it. Good. But you have not by making that promise dealt with the temptation you will face when you and some other real person fall mutually and truly in love, yet for some good reason cannot marry.

You promise honesty, and you mean it. Good. But you have not by making that promise dealt with the temptation that you will have when you have the opportunity to make some extra money that, to tell the truth, you could really do with, but by a means that will involve something just slightly underhand.

You promise fidelity to Christ, and you mean it. Good. But that will spare you none of the actual fear and doubt that will come to you if someone holds a gun to your head and says, “Deny Christ or die!”

The fact is, we cannot commit ourselves totally and irrevocably to God merely by intending to do it or wanting to do it or saying that we will do it. Trusting God is something that has to be learned. And so long as we do not understand that, so long as we imagine that we can of our own will and strength be faithful to God, so long we show that we are not actually trusting God at all, we are simply trusting ourselves. We will not learn what dependence on God is except through having our self-dependence, our trust in ourselves, regularly, slowly, and painfully, broken. That is Christian orthodoxy, Catholic and Protestant, and any who do not understand it understand little about themselves and less about the gospel of Jesus Christ. True confession of failure, honestly and bravely made, whether silently in the depths of the heart or at formal confession in the presence of a priest – that is the mark of one who truly trusts in God. Our requests for penance, advice, and absolution – those are the real signs that we have given up relying upon ourselves. Those whose hearts are broken by the knowledge of their sins and the wonder of God’s forgiveness – those who are the ones who are committed Christians, and those are the ones whom Christ claims as his own. Think again of the twelve disciples. Every one of them failed Jesus when the chips were down. Yet Jesus used those twelve disciples anyway, as chosen instruments in the founding of his church.

So commitment to Christ is a very strange thing – for the fact is, we, sinners that we are, learn what such commitment means not by succeeding in it but by trying it and failing in it and then turning back to God anyway. Every failure that brings us to ask pardon of God brings us back to our Baptism, wherein we were committed to Christ in the light of Christ’s death, and so our Baptism points us to Calvary. The real truth about commitment to Christ is that we could not even begin to seek it were not that God in Christ is already committed to us and is seeking us, as a lamb slain for our sakes from before the foundation of the world.

So – what are we to say of this ordinary, run-of-the-mill Episcopal Church, so full of redeemed sinners, that is ours? Does it really know nothing of commitment? If you think that,then look a little closer. What, for example, of the present occasion? Tonight there stands before us and before God Pamela, a modest, gentle, wise woman, who is committing herself in a very special and public sense. Just listen to the particular commitments she is about to make, as the Prayer Book describes them.

She promises to be “faithful in prayer, and in the reading and study of Holy Scripture,” she promises to “look for Christ in all others, being ready to help and serve those in need,” she promises “in all things” to seek “not her own glory but the glory of Christ.” And I dare say I know her well enough to know that she means those promises and intends to keep them, from the bottom of her heart.

Now if the order and discipline of Catholic Christianity means anything at all to you, if you have ever found yourself helped by the ministry of an ordained person, either in public worship or in private counsel, then you will know how useful it is for the church that God gives some, like Pam, to undertake these promises and this office.

But of the special commitments she makes tonight the same thing is true as we have already said of all Christians’ more general commitments: she will not be able fully to sustain them. When Saint Paul spoke of the apostolic ministry, he asked rhetorically, “Who is sufficient for these things?” And the answer he meant us to hear is obvious: “No one!” Paul was certainly well aware that he was not sufficient.

So it will be that Pam will never, after today, hear or read those promises in the Ordination Service without feeling a measure of guilt and failure. She will live for the rest of her life with the ever-increasing knowledge of chances to love and to be obedient that have gone forever.

What does this mean?

Does it mean that she ought not to make such commitments? Of course it doesn’t mean that! We’ve already said – we learn commitment to Christ by making it and failing in it and picking ourselves up and going back to Christ and trying again anyway – again, and again, and again.

So, what does it mean?

It means, first, that those of us who call ourselves “the church,” Pam’s fellow Christians, must be gentle with her, as we expect God to be gentle with us. Just because she has bravely undertaken these public commitments, do not demand of her that she always feel confident, faithful, bright, and loving. Do not require that she always be both happy and useful. Remember that she is still like you: struggling to be faithful, yet sometimes forgetting; trying to be obedient, yet not always knowing why, or even in what direction obedience lies. Remember that she like you is sometimes lonely and frightened and sad.

Secondly, it means thatwe who call ourselves Pam’s fellow Christians must try to minister to her and to nourish her with the same gospel with which she is undertaking to nourish us: for Christian ministry is not to be one way. As Saint Paul said, it is only by bearing each other’s burdens that we fulfil the Law, the Torah, of Christ. And here, suddenly, is the joy: for to minister to Pam from the gospel will be to remind her that in the last analysis the ministry she attempts is not hers at all, but Christ’s. It will be to remind her that it is, by God’s grace, Christ who is the good shepherd, and not she; and that Christ is her shepherd as much as yours. It will be to remind her that while of course we want her to take her commitments seriously, still she is not to take them too seriously or more seriously than the love of God. The fact is, God knows very well that our best commitments are mostly impossible for us for the moment. But God does not ask of us the impossible. Did we think for God’s sake that God expected us to be successful? No.It is the world, the flesh, and the devil – and, I might add, some schismatically minded preachers – who demand success. God only asks that we try to be faithful.

As for you, Pam, what all this means for you quite simple. You must say your prayers, try to be a useful and loving sort of deacon – and later, please God, a useful and loving sort of priest – and always try to admit (at least to God) when you’ve blown it. If you will just do those three things, you’ll be quite all right, and so will those round you. For Christ is the beautiful shepherd, and Christ will finally take the most bumbling efforts of us most incompetent sheepdogs and turn them to something glorious. And even though life lay upon us a cross, yet God who is our Father and our Mother, our Savior and our most gracious Sovereign, will in the end bring us all to the fellowship of blessed Mary and the company of angels and saints, and to a crown, not because we were all that deeply committed, as Christians or as deacons or as priests, but because God is committed to us, and God is faithful. And not our commitments but the faithfulness of God is the beginning and the end of the gospel. Amen.

LSD

Peter has a Bad Moment: a Note for the Parishes in Central Exeter

Proper 17A. For the Gospel: Matthew 16.21-28

This morning’s gospel belongs very closely with the gospel story we heard last week. Last week, you may remember, we heard Jesus’ question, “Who do you say that I am?” and Peter’s response—what we sometimes call his “confession”: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the Living God”. To which confession Our Lord said, “Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jonah, for flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father in heaven.”

So far, so good. But what does it mean to be the Messiah? What does it mean to be Son of God? This, the evangelist tells us in the section appointed for this morning’s gospel, is what Jesus now proceeded to show his disciples. It would not be the triumphal progress for which I dare say they were hoping—I know that’s what I would have been hoping. No, it would be something quite contrary to that.

“From that time on, Jesus began to show his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem and undergo great suffering at the hands of the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised.”

Peter, very understandably, is appalled by this.

“And Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him, saying, ‘God forbid it, Lord! This must never happen to you.’ But he turned and said to Peter, ‘Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling-block to me; for you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things.’”

This is a terrible moment. No one else (other than Satan himself) is called “Satan” in the entire gospel narrative: none of those we might think of as its “villains”—not Caiaphas, nor Pilate, nor even the traitor Judas. For Peter alone is reserved the title “Satan”—“Adversary”!— for that is what the Hebrew word satan means. And indeed, Jesus’ “Get behind me, Satan!” must put us in mind of the “Away with you Satan!” with which he earlier dismissed his adversary at the time of his being tested in the wilderness, at the beginning of his ministry (Matt. 4.10).

Poor Peter! In almost no time at all, it seems, he has gone from hero to zero. “Stumbling block”! The Greek word is skandalon, whence we get our English word “scandal”. In Greek it is a very strong word indeed, and means “trap” or “snare”. So Peter, who had earlier been told that he was the “rock” upon which the church would be built, the church that would be stronger than the gates of Hades—that is, stronger than death—is now told that he is also another kind of rock—a rock that gets in the way and trips you up! Faced with what Paul called “the stumbling block” of the cross (1 Cor. 1.23) Peter has himself become a stumbling block. What on earth has he done to merit this terrible rebuke?

It is not so much that the ways of God are inscrutable, and therefore beyond Peter. Of course they are that, but we must not use that as an excuse to avoid what is actually quite straightforward—as straightforward in its way as the prophet Micah’s, “He has told you what is good— and what does the Lord require of you, but to do justice and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6.8). The straightforward essence here is that the way of God’s son, God’s anointed cannot be a way of triumph unaccompanied by pain, because (as Jesus pointed out to Satan in the episode that we call “the Temptation” [Matt. 4.1-11) it is the way of obedience to God, which is to say, the way of love. In this present world that inevitably means a way of suffering, greater or lesser. As C. S. Lewis said, “The only place outside of heaven where you can be perfectly safe from all the dangers and perturbations of love is Hell.” Jesus’ love is perfect, and it will bring him to his cross. And he knows it.

“Then Jesus told his disciples, ‘If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.’”

Those who of us who want to follow Jesus—and I stress, as does the evangelist’s Greek, “want to (θέλει)”: for it is always a matter of our free choice—those of us who want to take that path must do our feeble best to emulate such love in our own lives, doing what we can to take up and bear gracefully whatever “cross” is laid upon us, always remembering that the essence of true humanity is, as the old play has it, to “love thyself last” (Shakespeare and Massinger, Henry VIII III.ii.521). That is what it means to follow Jesus. That is why, when Jesus says, “get behind me” to Peter he is actually assigning him the place where we all need to be—in truth, the only place where we can be with any degree of either realism or safety: behind Jesus. And as close behind him as we can get! Then, when he comes in the glory of his Father to face us as our judge, we may by his grace be enabled to raise our faces to his and look into his eyes. God grant us that! Amen.

Jesus and the Canaanite Woman: a Note for the Parishes in Central Exeter

Proper 15, Year A.

For the Gospel: Matthew 15.22-28

You sometimes hear people who think that they are being marvellously orthodox saying things like, “If Jesus was God, he must have known everything.” Actually, when they say things like that they aren’t being orthodox at all. They’re espousing a form of the docetic heresy (the name comes from the Greek verb dokeō, meaning “to appear” or “to seem”). Docetists said that Jesus wasn’t really human at all. He was actually God appearing or seeming or pretending to be human. In other words (and if you will forgive the analogy) he was like a chocolate Easter egg covered in coloured paper. It looks like a coloured egg, but really it’s just chocolate underneath! The New Testament, however, says that “the Word became flesh” (John 1.14)—really became it!—which is to say, Jesus was truly a human being, with all the limitations that go along with that. And among those limitations, of course, is the plain fact that we don’t know everything, and what we do know we have to learn. And, of course, that’s exactly how St Luke describes Our Lord. As he grew to manhood, Luke says, he “advanced in wisdom and stature” (2.52). In other words, he learned things!

Now one of the reasons why I find today’s gospel interesting is that I believe it gives us a glimpse of Our Lord doing just that: learning something, advancing in wisdom. Some of my old students may remember I used to say to them, “There’s only one time in the gospels when Jesus loses an argument, and it’s to a woman and a foreigner.” This is the story I was talking about.

Jesus, the evangelist tells us, was approached by a woman of Sidon, a Canaanite, in other words, a pagan—the very kind of person whom, according to Moses, the good Israelite should “utterly destroy” (Deut. 20.17). She addresses Jesus with profound respect and asks for healing for her daughter. “Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David,” she says, ”my daughter is tormented by a demon!” At first Jesus simply says nothing—he gives her, as we say, “the silent treatment.” Then, when his disciples fuss at him to send her away, he points out that his primary mission must be to his own people. “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” Her response is to kneel before him and say, “Lord, help me!” His response—“It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs”—embarrasses us, and it should. It is an insult, although no doubt it is precisely what Jesus had been told by at least some among his teachers. Israel is God’s child, and Israel’s election must be taken seriously. Non-Israelites are abominable because they do not honour the God of Israel. In their uncleanness they are like dogs, and it would be a poor father who gave the children’s dinner to the dogs!

Insulted and rejected though she has been, the Canaanite woman neither sulks nor turns away. Rather, she stands her ground, turning Jesus’ family metaphor on its head: “Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table”—a response that shows wit and magnanimity, but above all faith. She maintains her courteous address, continuing to call Jesus “Lord”. She denies neither that Jesus’ primary mission is to Israel nor that the Israelites are God’s “children”, the elect, first in God’s love. She insists, however, on a truth prior even to God’s election of Israel—a truth she seems to know instinctively even though she has surely never read the Scriptures, a truth that was apparently (as St Paul would have put it) “written in her heart” (cf. Rom. 2.15): namely, that “the LORD is good to all, and his compassion is over all that he has made” (Ps. 145.9). So then, even mere dogs under the table are surely permitted to pick up the crumbs the children don’t need! In insisting on this, she manifests the essential faith of Israel, the faith of Abraham, the faith of Moses. Like Abraham and Moses, she is willing to argue with God, a willingness that can be based on nothing less than her faith that God is just, good, and merciful. In doing so she shows herself to be at heart a daughter of Abraham.

Her effect on Our Lord is evident.

“O madam, great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish.” And her daughter was healed instantly.

So in this scene we see an occasion when, to use St Luke’s phrase, “Jesus advanced in wisdom.”

I recently came across some important observations about this story in David Brown’s beautiful book, Through the Eyes of the Saints. Commenting on the version found in Mark, where the woman is described as “Syro-Pheonician” rather than “Canaanite”, he writes,

it is not impossible that it was his [Jesus’] exchange with the Syro-Pheonician woman that led him to give a higher status to Gentiles in the divine economy than seems generally to have been true among his contemporaries. Certainly, all agree that it is an odd exchange, and so possibly may have been preserved precisely because the woman’s quick response led Jesus to think anew: his compatriots’ abusive term for Gentiles as like the despised wild dogs of the day just would not do. None of this can be proved, but, the more seriously we take New Testament scholarship’s contextualising of Jesus’ teaching within the thoughts forms of the time, the more likely such scenarios become.

Exactly! May God grant us all the faith, wit, grace and tenacity of the Canaanite/Syro-Phoenician woman. Amen.

Easter 2020: a note for the parishes of Central Exeter

I’ve been a priest now for nearly sixty years, and during the whole of that time this is the strangest Easter I’ve known. I’m told it’s the church’s job to give hope, and no doubt it is. But hope for what? For a return to that “normalcy” whose apparent security is always an illusion? [1]

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love,For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting. [2]

T. S. Eliot wrote those words in 1940, a year in which Great Britain was subject to an aerial bombardment that left people with very few certainties—not the certainty that the houses they lived in would be standing tomorrow, nor even the certainty that they themselves would still be alive. As that uncertainty loomed, King George VI in his Christmas broadcast to the nation quoted a poem that had been shown him by his thirteen-year old daughter Princess Elizabeth:

And I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year:

“Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.”

And he replied:

“Go out into the darkness and put your hand in the Hand of God.That shall be to you better than light and safer than a known way.”

So I went forth, and finding the Hand of God, trod gladly into the night.And He led me towards the hills and the breaking of day in the lone East. [2`]

The darkness in which we find ourselves, the darkness of Holy Week and the darkness of pandemic, are real. Let us not deceive ourselves about that. But darkness has never overcome the light and darkness and death do not have the last word. All around us there are signs of Spring, shoots of green, birds building nests. And the Easter salutation does not change:

Hallelujah! Christ is risen!

He is risen indeed! Hallelujah!

The last word is and forever will be Christ’s and it is a word of grace:

Lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.

1 One might add: shall we continue criminally to underfund the National Health Service, that same NHS whom we now call our heroes, even as they place their lives on the line for us—and in some cases die for us because they do not have enough of the personal protection equipment with which our successive governments of both parties should have seen they were provided?

2 T. S. Eliot, “East Coker” in Four Quartets.

3 Minnie Louise Haskins (1875-1957)”God Knows” in The Desert (1908).

The Word became flesh: text of a sermon preached at St Stephen’s, Exeter on Christmas Day, 2019

For the past few years, whenever I’ve preached at Christmas it’s generally been at Midnight Mass. That means, of course, that I’ve preached on St Luke’s story of Our Lord’s birth: Mary and Joseph coming to Bethlehem, no room at the inn, the stable, the shepherds’ visit, and at the centre of it all the Virgin Mother and her Child. And what a story it is! Even after two thousand years painters still love to paint it, sculptors to carve it, and poets and hymn writers to hymn it. Countless schools and churches around the world love to reenact it. The most cynical and morally beaten-up among us generally still have a moment when our hearts are strangely warmed as we gather round a Christmas crib or watch a Nativity Play, however simply (or even badly) written or performed.

That, then, is what we get to think about at Midnight Mass.

By contrast, in the light of Christmas morning, while not forgetting that wonderful story—our hymns are still reminding us of it—while not forgetting that, the church now asks us to pay attention to the passage from St John that we just heard, the Prologue to his gospel. In it John tells us his version of the same story. And it’s different. Very different! Moving from Luke’s stable to John’s Prologue is like moving from a cosy thatched cottage to a solemn temple.

John’s version begins back in time, indeed, before time. No doubt the evangelist had read in his Bible that “in the beginning” God created the heavens and the earth. So he now starts by pointing out that in that same “beginning”, even before God created anything, “the Word”—God’s Word—already was! (1.1) Through that Word, he tells us, the universe itself was uttered into being (1.3). In that Word was life, and the life was the light of humankind—the true light, that enlightens us all, the light that continues to shine throughout our history (1.4). And although that history contains much that is dark, still “the darkness did not overcome” it (1.5)—the “overcome” of our NRSVs being something of an under-translation: John’s Greek word is “κατέλαβεν”—”grasped” or “apprehended” — a rather brilliant choice, since it implies not only that darkness has never defeated the light but also that it has never understood it (1.5). As the colloquialism has it, when it comes to light, the darkness has simply never got it.

After a couple of digressions about John the Baptist and other things, John comes to the affirmation that is heart and centre of the Christmas story as he tells it: “the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us.” “Flesh”—σάρξ: a word that to John’s first hearers would have spoken of our humanity in all its frailty and transience. I dare say neither John nor his hearers could think of anything more utterly different from God’s eternal Word than “flesh”, and yet “flesh” is what John says the eternal Word “became”—ἐγένετο: his choice of word indicating what happened here was no mere appearance, like an actor putting on a costume or a mask, but real.[1] St Augustine of Hippo declared that throughout his life before he became a Christian, as he struggled to find wisdom, he’d come across other sources that spoke to him of God’s Word. But only in Christianity did he find it written that “the Word became flesh” (Confessions VII).

Just why does the church want us to hear all this—in effect, a summary history of the universe—on this particular day? I think because it tells us something of what the Bethlehem story means. It’s only too easy for us to sentimentalise that story. We can hear it and at the end of it say, “Yes, it’s beautiful. But it was all a very long time ago. Next week we must go back to work and the world will not have changed. Life will still be the same old same old.”

And that’s precisely where St John says we’re wrong. “No,” he says. “If you think that, you simply haven’t got it. You’re like the dark that surrounds the light but never understands it. What happened at Bethlehem that night involved a union between ourselves and God that changes everything, a union that is staggering if not preposterous, a colossal, breathtaking paradox. Don’t you hear it? The Word became flesh.”

For all the lightness of her verse, Christian Rosetti expresses that paradox very firmly in her carol, “In the bleak midwinter” [2]—indeed, she compels us to pay attention to it:

Our God, heaven cannot hold him,

Nor earth sustain;

Heaven and earth shall flee away,

When he comes to reign.

So much any follower of the God of Abraham, any faithful Jew, Moslem or Christian may affirm. But then comes the affirmation that only a Christian can make:

In the bleak midwinter

A stable place sufficed

The Lord God Almighty,

Jesus Christ

It is precisely our humanity, our back-to-work-and-the-world-hasn’t-changed humanity, our it’s-only-more-of-the-same-old-same-old humanity, which God has consecrated and tied to God’s own self in the birth of Jesus Christ. That’s what John tells us. The Word has become flesh.