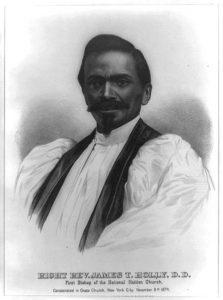

James Theodore Holly, Bishop of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Text of a Sermon preached by Professor Cynthia Crysdale in the Chapel of the Apostles on the 8th November 2017

If this sermon were to have a title it would sound a bit like a Dr. Seuss book: “Oh the Stories we tell!” I want to talk about three sets of stories today. The stories themselves are fascinating but my main focus is on just how these stories came to be, the meaning makers who generated them and the reasons they were crafted.

If this sermon were to have a title it would sound a bit like a Dr. Seuss book: “Oh the Stories we tell!” I want to talk about three sets of stories today. The stories themselves are fascinating but my main focus is on just how these stories came to be, the meaning makers who generated them and the reasons they were crafted.

James Theodore Holly was born a free African American in Washington DC in 1829. Baptized and raised in the Roman Catholic Church, Holly severed his ties when that denomination refused to ordain him because of his race. He joined the Protestant Episcopal Church while living in Windsor, Ontario, and after returning to the U.S. was ordained a priest in New Haven Connecticut. In 1874 he was consecrated as a missionary bishop of Haiti, becoming the first African American bishop in the Episcopal Church. In 1878 he attended the Lambeth Conference, the first Black to do so.

These are the facts. But within Holly’s story lies his passion for finding a voice for the voiceless. While he was living in Canada, he spent four years helping former slave Henry Bibb edit his newspaper, The Voice of the Fugitive. In the same year that he was ordained he co-founded the Protestant Episcopal Society for Promoting the Extension of the Church Among Colored People, a precursor to the Union of Black Episcopalians. He was determined to find a place, both literally and figuratively, for African Americans to thrive. Holly was a delegate to the first National Emigration Convention in 1851. He saw Haiti, a country where slaves had led a successful revolt and founded their own nation, as a place where Blacks could bind together. He believed that bringing Anglicanism to Haiti would contribute to its development. In spite of rebuffs from both Congressmen and the Board of Missions—several times over — in 1861 Holly took 110 men, women, and children from New Haven to Haiti.

The first year went badly. Forty-three of his emigrants died of infectious diseases, including his mother, his wife and his two children. He persevered nonetheless, becoming a Haitian citizen and eventually convincing the Board of Missions to sponsor his work. As Bishop he continued to live and work in Haiti, returning rarely to the U.S. He remarried and with his new wife Sarah, had nine children. He died in Port-au-Prince in 1911 and is buried there.

Holly worked to make a visible minority less invisible, in both church and society. But his story itself illustrates the way the Church has told its history. I learned about Holly by reading The Church Awakens: African Americans and the Struggle for Justice, a website of the Archives of the Episcopal Church.[1] This website was created in 1993 in response to the 1991 General Convention’s call to address institutional racism and its pattern of forgetting. Ironically, this pattern of forgetting arose as a post-civil rights era phenomenon. Having made structural and policy changes, the conscience of the Church seemed to be relieved of the need to remember the “historic harm of three centuries of racism.” The Archives mined its resources to recover what were otherwise lost memories. The stories they tell are as disturbing as they are enlightening: holy women and men such as Holly are brought to light, but the recalcitrance of embedded prejudice in the church is most visible. Sewanee plays its part here, and we have much to do still to repent, retrieve and renew our history.

The second example of storytelling comes from our Old Testament lesson today. The Book of Deuteronomy stands as a bridge between Sinai and the Promised Land. Set in the moments just before Israel moves to cross the Jordan, its theme is obedience and loyalty. The future dangers that are highlighted are not so much from warfare but from success: the dangers of adopting foreign gods and worshipping at local shrines. A second telling of the law (deuteros nomos—hence “deutero – nomy”) is a necessary reminder to establish again the covenant relationship between God and God’s people.

But while law and rules and obedience are the main threads, they are woven with narrative wool. How many of you have children who complain about rules: “Who does which chores? Why do I have to wash my hands? Brush my teeth? Go to church?” Deuteronomy tells us that the way to respond to such questions is to tell a story. When your children ask you, “What is the meaning of these decrees and statutes?” you must tell them, “We were Pharaoh’s slaves in Egypt, but the Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand. The Lord displayed before our eyes great and awesome signs and wonders against Egypt, against Pharaoh and all his household” (Deut. 6:21-22). This narrative context is repeated at the end of Deuteronomy. “When you bring the first fruits of the harvest as a thank offering to the priest, you shall say: ‘A wandering Aramean was my ancestor; he went down into Egypt and lived there as an alien, few in number, and there he became a great nation, mighty and populous. When the Egyptians treated us harshly and afflicted us, by imposing hard labour on us, we cried to the Lord, the God of our ancestors; the Lord heard our voice and saw our affliction, our toil, and our oppression. The Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with a terrifying display of power, and with signs and wonders; and he brought us into this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey’” (Deut. 26:5-9).

But let us notice that this narrative also has its dark side. Just after the passage in Deuteronomy 6, chapter 7 continues with instructions about how to treat the neighbours in the Israelites’ new home. Once God has cleared away seven mighty nations from the land, “when the Lord your God gives them over to you and you defeat them, then you must utterly destroy them. Make no covenant with them and show them no mercy. . . . this is how you must deal with them: break down their altars, smash their pillars, hew down their sacred poles, burn their idols with fire” (Deut. 7: 2, 5). Yes, the theme is that God alone must garner the loyalty of Israel. But there is no avoiding the fact that God is ordering genocide. Our Biblical tradition – the stories we have told of God’s gracious work – are filled with prejudice that our generation must acknowledge. While we cannot change history, we can face the dark side in our heritage with honesty. We need to be attentive: we must read between the lines and, while not excusing the past, at the very least take care not to hand on embedded intolerance.

My third example of story telling is about making meaning in the present as events unfold in the midst of confusion. When the twin towers were attacked on 9/11 U.S. airspace was quickly closed and all planes in the air ordered to land. A number of commercial flights were over the Atlantic – too far along to return home. The closest airfield was in Gander, in Newfoundland: an airfield very much in use during World War II but rarely used in recent decades. One by one planes from London, Dublin, Frankfurt, and Moscow, among others, were ordered out of the sky, most pilots still ignorant of the reason why. In all, 38 jumbo jets landed in the space of a few hours, carrying 6500 passengers and crew, 17 dogs and cats and 2 rare bonobo chimps. The population of Gander is itself just under 10,000. But it became clear as this drama unfolded that those planes were not going to take off again anytime soon.

The people of Gander and surrounding fishing villages did not see potential terrorists or imminent danger. They saw people in need and set out to help them. The people who disembarked – some after 28 hours on a plane – came from 100 different countries with thousands of different reasons for traveling that day. There were refugees from Moldova on the way to a new life in the U.S.; several couples coming home with newly adopted children from Russia; a high-profile executive from the elite fashion designer, Hugo Boss, en route to New York for fashion week; Lenny O’Driscoll, who had grown up in Newfoundland but hadn’t been back for decades. There were Muslims, Christians and Jews, gay couples, young and old, single and married. One couple who met that day fell in love and were eventually married.

The people of Gander and surrounding fishing villages did not see potential terrorists or imminent danger. They saw people in need and set out to help them. The people who disembarked – some after 28 hours on a plane – came from 100 different countries with thousands of different reasons for traveling that day. There were refugees from Moldova on the way to a new life in the U.S.; several couples coming home with newly adopted children from Russia; a high-profile executive from the elite fashion designer, Hugo Boss, en route to New York for fashion week; Lenny O’Driscoll, who had grown up in Newfoundland but hadn’t been back for decades. There were Muslims, Christians and Jews, gay couples, young and old, single and married. One couple who met that day fell in love and were eventually married.

All were welcomed. The school bus drivers, who were on strike, left their picket lines to ferry the “Plane  People” to a host of school gyms, church basements, and a Salvation Army camp in the woods. Bakeries went into overdrive, pharmacies cleared their shelves of toiletries, and casseroles came out of ovens by the dozens. What will live in memory as a day of terror and grief, became at the same time a day of comfort and healing. The stories abound and have been collected into a book called The Day the World Came to Town,[2] now made into a Tony awarding winning Broadway musical – Come from Away.[3]

People” to a host of school gyms, church basements, and a Salvation Army camp in the woods. Bakeries went into overdrive, pharmacies cleared their shelves of toiletries, and casseroles came out of ovens by the dozens. What will live in memory as a day of terror and grief, became at the same time a day of comfort and healing. The stories abound and have been collected into a book called The Day the World Came to Town,[2] now made into a Tony awarding winning Broadway musical – Come from Away.[3]

Of all the stories, one has had an especially compelling ring for me. During the second day at the Elementary school in Glenwood, one of the volunteers noticed that a man and two women had not eaten any of the food put before them. When she enquired about this, it turned out that they were Orthodox Jews. The Jewish population of Newfoundland is miniscule but the hosts helped Rabbi Levi Sudak set up a Kosher kitchen in the faculty lounge of the school. The Rabbi had been en route to New York, where the founder of his particular Jewish sect is buried. His intention was to visit the grave and return home to London where he works with disenfranchised youth. Now he wondered what God had in store for him. Why deposit him on this rock in the Atlantic with no fellow Jews in sight? As the week moved on his question intensified. By the time his plane was released to fly again it was Friday evening – neither he nor the two other Orthodox women would travel on the Sabbath. As his plane took off for New York without him, he wondered again why he had come to this isolated Gentile island.

The next day a man called Eddie Brake came to visit him. Eddie Brake was over 70 years old. He was born to a Jewish mother and father in Poland in 1930. He did not know what name his parents had given him or even their family name. He only knew that just prior to WWII his parents had arranged to have him smuggled out of Poland to England. He was adopted by an English couple, who then moved to Cornerbrook, Newfoundland. He was told never to let anyone know that he was Jewish. If he mentioned it at all his parents beat him. Even as an adult, when he decided to tell his wife and grown children of his identity, they scorned him and hushed him up. Now, here he was after all these years, sitting in front of a Rabbi. He told him that all these years he had never stopped thinking of himself as a Jew. His walking stick had engraved on it a small star of David. Sometimes at night he would wake up singing the religious music he had learned as a child. Eddie and the Rabbi talked for over two hours. When they were done, Eddie returned home and the Rabbi made plans to return to London. He never got to New York, but he now knew why he had made this journey.

The story of that week in Gander Newfoundland is a story of having to create meaning in the midst of tragedy, with people who had never intended to come together. There was tension for sure – the narrative unfolded in a context in which it was not clear whether these planes themselves were intended as weapons, or whether some of the passengers were terrorists on a mission. But those who lived on that particular rock in the Atlantic reacted as if those who descended on them were their own mothers, fathers, children, grandchildren, neighbours. No hatred, no anger, no fear of those who come from away.

We cannot avoid the terror of memories that haunt us. As a community, we have the task of owning the dark places of our past and living in the midst of current grief and sorrow. Each of us has secrets we don’t tell, sins we avoid recalling, resentments or fears that linger in deep places. But as disciples of Christ it is our job to tell stories – to find the gospel and preach the gospel ever anew. What if we lived AS IF resurrection could illumine the very darkest places of our past? What if we lived AS IF the Lord ruled even the tragic present? AS IF nothing could separate us from the love of God? AS IF we could meet everyone without fear? AS IF those who come from away are in fact our dearest neighbours?

[1] Go to https://www.episcopalarchives.org/church-awakens/

[2] Jim DeFede, The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland (New York: Harper Collins, 2002).

[3] Come from Away, book, music and lyrics by Irene Sankoff and David Hein.