Month: March 2019

Thoughts on the Unspeakable. Text of a sermon written for St Olave’s Church Exeter, for the 3rd Sunday of Lent

For the Psalm 63:1-9; for the Gospel, Luke 13.1-9

On television this week I watched an interview with a man who was at the mosque in Christchurch when the shootings happened. He spoke about it hesitatingly for a few minutes and finally stopped, saying in effect, “I just have no words for what happened. I can’t talk about it.” Who wouldn’t sympathize? There are some things so awful, so appalling and outrageous to our every decent instinct that it is almost impossible to talk of them rationally or reasonably. We naturally call them “unspeakable”.

spoke about it hesitatingly for a few minutes and finally stopped, saying in effect, “I just have no words for what happened. I can’t talk about it.” Who wouldn’t sympathize? There are some things so awful, so appalling and outrageous to our every decent instinct that it is almost impossible to talk of them rationally or reasonably. We naturally call them “unspeakable”.

But does that mean we just let such things pass? That we have no questions? Surely not! Muslims, Christians, Jews—we all believe in the God of Abraham. We believe that God cares for what God has made, that God is Merciful and Compassionate. Why then does God allow these things to happen? Those fifty people in the mosque at Christchurch had come together to pray to the God of Abraham. What was God up to, that God didn’t protect such people? How do we explain such events?

One move is to say that such people were sinful, and therefore God, who is righteous, has punished them. That might seem to most of us a little hard to sustain when one of those killed at Christchurch was only three years old, but I am well aware of some who would offer such an argument. It’s the same argument as is offered in the Old Testament to Job. Job is a good man who suffers terribly. His friends comfort him by telling him he must have committed some serious sin and what he needs to do is repent and then God will make everything right. But Job is adamant. He’s done the best he can to be a decent human being and he doesn’t see why he should be treated like this. “Let God come and face me and let’s have it out,” he says, or words to that effect.

Would he contend with me in the greatness of his power?

No; but he would give heed to me.

There an upright person could reason with him,

and I should be acquitted for ever by my judge. (Job 23.6-7)

The odd thing is, God enters the story at the end of the book and God says that Job is right. God doesn’t run the world like an angry boss who clobbers you if you step out of line. Job’s friends are wrong.

All of which brings us to the gospel passage that was set for today—the passage we just heard from St Luke. Jesus and those round him are talking about two local disasters that have disturbed and distressed people. One is evidently a result of human cruelty—the Roman governor has ruthlessly suppressed and killed a group of Galilean worshippers. For some reason they’ve been regarded as a threat to imperial security and so, as we hear the story, the governor has “mingled their blood with their sacrifices”. The other is a more or less accidental disaster—a building in Jerusalem called the tower of Siloam has collapsed and killed eighteen people. They were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. How are such awful things to be explained? Apparently there are those around Jesus who use the same argument as Job’s friends: “Ah, they must have been terrible sinners for God to punish them like that!”

If so, then Our Lord utterly rejects that idea.

“Do you really think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans?” he says. “No, I tell you… Or those eighteen who were killed when the tower of Siloam fell on them—do you really think that they were worse offenders than all the others living in Jerusalem? No, I tell you!”

“But,” he adds, “I’ll tell you this: if you don’t stop thinking like that, one day you’re going to find yourselves in the same situation they’re in!”[1]

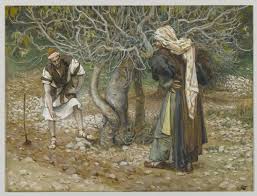

What then? Does our Lord have some better “explanation”? Actually, he doesn’t. Or at least if he does he doesn’t tell us about it. Instead, he tells us a rather strange little story about a fig tree. This tree is barren—which is to say, it’s useless. It cumbers the earth, uses up resources and produces nothing.

“Yank it out and burn it,” the landowner says, reasonably enough.

“Yank it out and burn it,” the landowner says, reasonably enough.

But—

“Wait!” says the gardener. “Let it alone for one more year!”

Nor is that all, for the gardener himself will put some effort and resources of his own into this—“Let it alone… until I dig round it and put manure on it. If it bears fruit next year, well and good; but if not, you can cut it down.”

And there the little story ends. No certainty is offered, no promises, only a modest hope and a plea for patience.

So how are we to explain such tragedies as those we are speaking about? Well, perhaps we need to learn from the man on television who said of the Christchurch shootings, “I can’t talk about it.” Or from what we’re told of Job’s friends, who did fine so long as they didn’t say anything, but really screwed up when they started to talk. But perhaps above all we need to learn from our Lord, who offered no explanation, but only a plea for patience. The truth is, we cannot “explain” the Christchurch shootings—or Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or the Holocaust, or any of the other hideous atrocities that litter human history—and especially we cannot “explain” them if by “explain” we mean, “show how they were good things really”. They weren’t.

Why do we seek God at all? Is it because God “explains” things? I doubt it. I think we seek God because we want God. We long for ultimate love, for faithfulness at the heart of the universe. We seek God because, as the psalmist put it this morning,[2] we are thirsty for God:

My flesh also faints for you

as in a dry and thirsty land where there is no water.

(Ps. 63:1-2)

The Song of Songs has it right. We seek God (and incidentally, God seeks us) as lovers. And what is the quality of love? Paul said it simply enough—“love is patient”.[3] Which brings us back to our gospel passage and the odd little story that Jesus told. If God is our lover, and we love God, then we must do what lovers always have to do, and be patient with each other. We all know—God knows, and I certainly know it!—that God has to be patient with us, with me. How about us in return exercising some patience with God?

That doesn’t mean trying to pretend that there are no problems or questions—questions such as the Psalmist asks again and again, “Why?” “Why do the wicked prosper?” questions such as Our Lord himself asks as he hangs on the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” But it does mean being willing to live with those questions. It means being willing to address them to God, frankly expressing our fear, our disappointment and our anger, just as the psalmist and our Lord do. One of the great mistakes we can make in prayer is to suppose that we always must be polite, however badly we feel. That is a sure way to end any relationship. Whatever we have to offer, however awful, God is presumably big enough to take it.

Being patient also, of course, means what it says: it means being patient, hanging in there! One of the most powerful moments in C. S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters[4] is when Screwtape, writing of course from the devil’s point of view, says “our cause is never more in jeopardy than when a human, no longer desiring but still intending to do [God’s] will, looks round upon a universe in which every trace of Him seems to have vanished, and asks why he has been forsaken, and still obeys.”

So what of explanations? There’s a story I love about the great ballerina Margot Fonteyn. After she’d completed a particular dance she was asked to explain it. She looked at her questioner with that peculiarly devastating scorn that only a stunningly beautiful woman can inflict without even intending to, and replied, “If one could explain it, one would not have needed to dance it.” That first Good Friday, at the end of Our Lord’s journey to Jerusalem, Jesus died. He was the best person who ever lived, and he was crucified. What then? God did not explain the cross. What God did do was raise him from the dead. And this too, I suppose, was a kind of dance:

They cut me down

And I leapt up high,

I am the life

That’ll never, never die.[5]

There is so much around us that we do not understand, and God does not explain that, either. What God does do is give us a promise through his Son: “Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up at the last day” (John 6:54). In light of that promise we shall in a few moments approach this altar. In light of that promise we dare now to place our trust in God, in words that the church has taught us:

We believe in One God…

[1] I take Luke’s μετανοῆτε, normally translated “repent”, in its more basic sense of “to change one’s mind or purpose” (see LS μετανοέω), and I think that NRSV “as they did… just as they did” (ὁμοίως… ὡσαύτως) are the key words here. The point is, the view that “if they’re suffering, they must have sinned very badly” works well for us until we start to suffer ourselves, as sooner or later, in some measure, we all do. Thus categorizing other people’s suffering leaves us feeling safe, for it says that they are different from us (they were great sinners!) and were therefore vulnerable. Our own suffering reminds us, however, that we are like them after all, with the same hopes and the same fears. Apropos the two disasters to which St Luke’s narrative refers, we have no record of them in any extant work from the time other than his, but there is nothing intrinsically unlikely or improbable about either. The slaughter of Galilean worshipers fits well enough with the character of Pilate as presented by Josephus (e.g. Ant. 18.3.2; Jewish War 2.9.4), and I am told that ruins still exist from a collapsed tower on the south eastern wall of ancient Jerusalem, dating from about this period.

[2] In its choice of Psalm the Church of England here follows the Revised Common Lectionary. The Episcopal Church and the Roman Catholic Church appoint Ps. 103 or part of Ps. 103.

[3] For the view of the Song of Songs here reflected, see Ellen Davies, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Songs of Songs (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox, 2000) 231-38, which I find very persuasive; also Robert B. Jenson, Song of Songs, Interpretation (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox, 2005).

[4] C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1942). There have, of course, been many editions since.

[5] Sydney Carter, “Lord of the Dance” (1963).

Thoughts on a Perfect World. Text of a Sermon preached at St Olave’s, Exeter, on the Fourth Sunday after Epiphany 2019

The Proper: for the OT Genesis 2:5-9,15-25

I’d like to spend a few minutes reflecting with you this morning on the passage from the Old Testament that we heard a few minutes ago.

It’s part of a collection of stories at the beginning of the Bible—the first eleven chapters of Genesis, to be precise—that scholars often refer to as “the Primeval History”. Most people have heard of these stories and have some idea what they’re about, even if they’ve never read them in the Bible—the Seven Days of Creation, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the murder of Cain, Noah’s ark and the Flood, and the Tower of Babel. What we heard this morning was the first part of one of those stories—the story of Adam and Eve.

Speaking of these stories generally, if I were asked to name some of the Prince of Darkness’s major achievements over the last two or three hundred years, I’d certainly include among them his solid success in distracting us from actually listening to them: persuading us instead to indulge ourselves in fatuous arguments about whether they are blown to pieces historically by Darwinian theories of natural selection, or whether they blow Darwin to pieces—questions that a moment’s intelligent consideration will tell us were surely about as remote from the concerns of those who first told them as was differential calculus from the concerns of my dog Hoover at supper time.

And that’s a shame, for these are marvellous stories. George Steiner says, “No stupid literature, art or music lasts.” If Steiner is right (and he is) then these stories that have gone on being told for four or so thousand years, give or take a century or so, must be very good indeed. What is it about them that makes them so good? That great west-countryman Samuel Taylor Coleridge said, “The strongest argument for Christianity is that it fits the human heart”—and I’d say that’s true of these stories. They are good because they fit the human heart.

So what of this morning’s story, or rather part of a story? Let me here come clean and admit that at first I was rather annoyed with the lectionary for only giving us part. I don’t like cliffhangers. I like stories to be finished. But then as I came to think about it, I decided that perhaps the lectionary rather does us a favour. It obliges us to look at the earlier part of the story of Adam and Eve apart from the sad tale of the serpent and their taking the apple and their fall from grace. Which means, in effect, that it obliges us to look at the storyteller’s vision of a world without wickedness, a world as God would like it to be. When one thinks about it, it was rather brave of our storytellers even to offer such a vision, since they presumably had no more experience of such a world than we have. Still, they did offer it, and here it is.

So what is such a world like? In the words of Louis Armstrong’s famous old song, “it’s a wonderful world”—an exciting, colourful world, full of amazing plants, amazing creatures and exciting things to do. Unlike other ancient stories of creation that have survived from the Ancient Near East, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, wherein the gods treat humanity pretty much as playthings, in this story God cares for humankind and talks to us, carefully setting us in the midst of this glorious world and actually giving us a role to play in it: to care for it and even, as the Hebrew hints more clearly than our English translations, in some sense to “serve” it (לְעָבְדָהּ). All the possibilities of this wonderful world are, moreover, ours for the enjoying. “Of every tree of the garden,” God says, “you may eat freely”. No asceticism here!

There is just one limitation, and it applies to “the tree of the knowledge of good evil”. We are not to eat of that. Why? What’s so special about that one? I confess I’ve always had some sympathy with Crowley’s objection to the whole thing in Good Omens:

“If you sit down and think about it sensibly, you come up with some very funny ideas. Like: why make people inquisitive, and then put some forbidden fruit where they can see it with a bit neon finger flashing on and off saying THIS IS IT!?”

“I don’t remember any neon.”

“Metaphorically, I mean.” (Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman, Good Omens [London: Corgi, 2019])

But there again, to be quite fair, this is perhaps not what the story-teller wanted us to think about. To begin with, we need perhaps to ask another rather obvious question, namely, what is meant by “good and evil”? People have argued about this for centuries, indeed, millennia. Of all the suggestions I’ve seen, I find most convincing the suggestion that the expression “good and evil” is an example of what grammarians and rhetoricians call “merismus”—a type of synecdoche whereby we speak of two extremes in order to mean the whole: as when we say “high and low” to mean “everywhere” or “from stem to stern” to mean “everywhere on a ship”. So “knowledge of good and evil” simply means “knowledge of everything”. The Greek oral poet Homer strikingly uses precisely this figure of speech when he has Odysseus’ son Telemachus say, “Already I think through all things and know them, the good and the evil” (ἤδη γὰρ νοέω καὶ οἶδα ἕκαστα, / ἐσθλά τε καὶ τὰ χέρηα) (Od. 20:309-10).

But who really knows everything? One would imagine, only God![1] So the command given to humankind here is actually quite straightforward: “You may eat of all the trees of the garden: which is to say, every possibility that your humanity offers you is yours. But do not attempt to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil: which is to say, do not attempt to be more than human, do not try to be God: for that will kill you.”[2] This is not, of course, a prohibition in any negative sense. It is no more or less than the kind of warning that every careful parent or good friend will offer: hot coffee can scald, fire can burn, nettles can sting: so be careful! You aren’t yet ready to deal with these things! [3]

But there is more. God also says, “It is not good for humankind to be alone.” According to the Christian revelation, even God, the One God, within the depths of the Divine Being enjoys relationship, the fellowship of the Triune God. As for the beasts, I remember being mildly surprised, but then immediately convinced, on reading some years ago in a book about dogs words to the effect that, “we love our dogs, and in their degree they do love us: but let’s not forget that they do also enjoy the company of other dogs!” Of course they do! And so it is with humankind. Adam has fellowship with God. And he has fellowship with the beasts. He even gets to name them! But even so, something else is needed: or as Genesis puts it, “there was not found for him a helper (עֵזֶר) to be alongside him (כְּנֶגְדּוֹ).” What then is needed? Well, of course, what is needed is another human being! There follows the wonderful little story of Adam’s sleep and the rib and Adam’s awakening and seeing the woman and his ecstatic cry—

She at last

is bone of my bone,

and flesh of my flesh!

Surely the first love lyric![4]

Let us be careful here to avoid two errors. First, let us avoid the suggestion I have sometimes heard that the creation of woman as the storyteller describes it makes her somehow inferior. Because she is created out of Adam (the argument goes) she is less than he, a mere appendage. On the contrary, one might just as well stand the thing on its head and argue precisely the opposite: just as Adam is created out of the dust, as its jewel and in some sense sovereign over it, so the woman in being created out of Adam is his jewel and in some sense his sovereign. Second, let us not misinterpret the description of the woman as Adam’s “helper” (עֵזֶר). “Helper” does mean “helper”. It does not therefore mean “inferior”. Indeed, the LORD God Almighty is at times described as Israel’s “helper”! (e.g. Ps. 33.20, 70.5) The word “helper” tells us what someone does. It does not tell us anything about their rank in any alleged pecking order, nor does it even imply that a pecking order exists.

But then, the mere fact that we have even referred to ideas such as these—superiority and inferiority, hierarchy and subordination, power and weakness—that shows that our mindset is already in the fallen world of the second part of our narrative, the fallen world of human disobedience. For it is there that we encounter such things as these, and they are presented very clearly as the fruits of our disobedience. In the perfect world of the former part of our narrative, relationship between the two human beings is simply about what the New Testament calls “fellowship” or “communion” (κοινωνία). It is above all about the wonder of not being alone. This wonder is nowhere more beautifully described than in the words with which the 1662 Book of Common Prayer spoke of marriage, though they are words which may surely be applied to all true friendship and fellowship: for certainly they too are honourable estates,

ordained for the mutual society, help, and comfort, that the one ought to have of the other, both in prosperity and adversity.[5]

It is the assertion of this estate that brings the narrative that we heard this morning to its triumphant conclusion: “And the man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed” (2:25). This is God’s the last and greatest gift to us: that we shall be with another person to whom we may be completely open and who will be completely open to us, a person to whom we may say, “I love you” and receive the response, “I love you, too.”

What are we to say to all this? We are we to say of Eden? The Genesis storyteller presents it to us as a glory that we have lost. Between Eden and ourselves an angel now stands with a fiery sword, and there is no going back. We may call this “myth” or “metaphor” if we choose, but we shall be very foolish if we think we have thereby given ourselves reason to dismiss it. Metaphor is how the human mind works at its most profound and creative, and the scribes of ancient Israel who wrote these stories down knew what they were talking about. They knew the human heart, and they describe life in the world as we know it, where there is much that is beautiful, but our joys are never complete or permanent; where again and again we seek to be as gods with each other, and where death is always the last enemy. As St Paul said, “In Adam, all die” (1 Cor. 15:22). We cannot go back. There is nothing to do but go forward, remembering that Paul also said it was God’s will “to have mercy on all” (Rom 11.32).

Mercy on all… but there is a cost to that, and a hint of that cost stands even at the end of this story. When the man and the woman had made their claim to godhead and were ashamed and could not cover their shame adequately, God (the storyteller says quietly) “made garments of skins for the man and for his wife, and clothed them” (Gen. 3.21). I say that the storyteller says this “quietly”, because it really is just slipped in: a single verse! If our attention had wandered for an instant we might have missed it. But it is there, and it brings into the story something that has hitherto had no place in the storyteller’s world: something so dreadful that even now it is not named. For there to be “garments of skins” something had first to die: and that death has availed to cover Adam and Eve’s shame. Here is a hint indeed for those who see at the centre of the Bible story another death, wherein God in Christ crucified binds Himself to us all to cover our shame. We are united with Christ’s death in our baptism in order that we may be united with Him in his resurrection (cf. Romans 6:3-4, Colossians 2:12-13). In that union is a promise that we shall finally be able, not to go back to Eden, but to go forward to that way of being “as God” for which we are indeed destined—to be “partakers of the divine nature”, as 2 Peter puts it. In that union is a promise that our fellowship with God and with each other will be made whole and we shall find ourselves, in C. S. Lewis’ words, “as we ought to be — between the angels who are our elder brothers and the beasts who are our jesters, servants and play-fellows.”[6] In that hope we come to God’s altar and pray with all the saints, “Amen. Come Lord Jesus!”

[1] So it will turn out in the second part of the story that the serpent’s temptation to humanity will be precisely this: that “you shall be as God (כֵּאלֹהִים), knowing good and evil” (Gen. 3:5).

[2] Robert Alter points out that the form that this takes at Genesis 2:17 is the form used elsewhere in the Scriptures for a death sentence, and renders it “doomed to die” (Genesis: Translation and Commentary [New York and London: Norton, 1996] 8).

[3] Interestingly enough, in the passage from the Odyssey that I cited above, Telemachus qualifies his claim by adding, “I am no longer a child [πάρος δ’ ἔτι νήπιος ἦα]”, and this would certainly fit with the idea that the problem with humanity’s claiming divine knowledge at this point is that we aren’t yet ready for it. That is why it will kill us. Other passages of Scripture (e.g. 2 Peter 1:4) seem to imply that at some point it is indeed our human destiny to be mature enough for such knowledge.

[4] The perfect commentary on this is still the Priestly assertion at Genesis 1:27:

So God created humankind in his image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

As Robert Jenson says, “according to the priestly wisdom of Genesis 1, only when we are created in these two forms is ‘the man,’ ha-adam, created at all. We are human only as male or female, and just so we are human only as both together; the Bible knows no gender-neutral humanity” (“Male and Female He Created Them” [2005]).

[5] 1662 Book of Common Prayer, Solemnization of Matrimony.

[6] C. S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength (London: The Bodley Head, 1945) Ch. 13.