Month: December 2017

Thoughts on the Nativity of Our Lord: Text of a Sermon preached by Mother Julia Gatta in the Chapel of the Convent of St Mary at Midnight Mass

For the Gospel: Luke 2:1-20

Saint Luke paints his nativity scene on a very wide canvas. He begins by solemnly invoking the Roman imperium: “In those days a decree went out from the Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered” (Luke 2:1). It is within this sweeping landscape—universal to those experiencing it—that his story about the birth takes place. A personage no less than Caesar Augustus has some role in it. The registration or census taking he demanded was for the purpose of taxation; for Rome, like other ancient empires, placed heavy tax burdens on their subject peoples. Why not have the poor subsidize the rich, if you are rich and powerful? Mary and Joseph bend themselves in compliance to Caesar’s decree, just as a little later Luke would show them obedient to the weightier law of God when they have their newborn son circumcised and presented in the Temple. But for now, the imperial decree prompts their temporary migration from Nazareth in Galilee to Bethlehem in Judea. It turns out that Caesar, who imagines that he’s in charge of the “whole world,” is actually an instrument of God, pressing forward the divine purpose and direction. For it is in Bethlehem that the greatest “son of David” must be born. Caesar, all unawares, is in fact obeying a power far greater than himself. And this is not the last turn-around and upending at work in this tale of grace. It happens again and again in the nativity story, foreshadowing the great reversal at the end of the gospel, when death itself yields to life.

Saint Luke paints his nativity scene on a very wide canvas. He begins by solemnly invoking the Roman imperium: “In those days a decree went out from the Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered” (Luke 2:1). It is within this sweeping landscape—universal to those experiencing it—that his story about the birth takes place. A personage no less than Caesar Augustus has some role in it. The registration or census taking he demanded was for the purpose of taxation; for Rome, like other ancient empires, placed heavy tax burdens on their subject peoples. Why not have the poor subsidize the rich, if you are rich and powerful? Mary and Joseph bend themselves in compliance to Caesar’s decree, just as a little later Luke would show them obedient to the weightier law of God when they have their newborn son circumcised and presented in the Temple. But for now, the imperial decree prompts their temporary migration from Nazareth in Galilee to Bethlehem in Judea. It turns out that Caesar, who imagines that he’s in charge of the “whole world,” is actually an instrument of God, pressing forward the divine purpose and direction. For it is in Bethlehem that the greatest “son of David” must be born. Caesar, all unawares, is in fact obeying a power far greater than himself. And this is not the last turn-around and upending at work in this tale of grace. It happens again and again in the nativity story, foreshadowing the great reversal at the end of the gospel, when death itself yields to life.

For all the majesty of his opening verses, Luke surprises us by describing the birth itself straightforwardly, plainly, simply. God enters the world quietly—not at all what we would expect: “While they were there, the time came for her to deliver her child. And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in bands of cloth, and laid him in a manger.” That’s it. It could be said of any birth, anywhere, at any time—except maybe for the manger part. Swaddling, as I learned when my granddaughter was born, is still practiced. It keeps baby warm and snug, imitating the secure confines of the womb. So Mary’s a good mother, doing what generations had done for their newborns before her. This is how God makes his home among us—softly, without fanfare, no fireworks. The first witnesses to the incarnation of the Son of God are a young couple trying their best under constrained circumstances and, of course, the animals.

Not in the manger scene nor even in the town precincts of Bethlehem—where we might expect it—but in an outlying area of pastureland, there is an outburst of divine radiance, this time taking the shepherds by surprise. Why shepherds? Well, why not? Young David was shepherding his father’s flocks near Bethlehem when he was called to become Israel’s great king. And the newborn child would be great like his father David—and even more like the Lord God, shepherding God’s own flock, becoming their Good Shepherd. So to shepherds near this city of Bethlehem renowned for its shepherd-king, an angel appears, bringing with her the shimmering, overwhelming divine presence and power: “and the glory of the Lord shone around them.” This is the Shekinah, the transcendent divine glory, the holiest of holy presences. No wonder the shepherds were terrified. Yet the angelic message is reassuring: “Do not be afraid”—a word we will hear at key junctures throughout the gospel when human beings have every reason to be afraid, humanly speaking. But the angel comes with a message that does not originate with mere mortals. She brings a message from heaven itself. God has something to tell us, something to speak into our fear-filled situation, a word become flesh. It is news—good news—but truly news: something utterly new.

“To you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord.” It is a breathtaking announcement, and I doubt it did much to alleviate—at least at first–the shepherds’ utter terror. It would take time to take it all in. The shepherds, like Mary, and like ourselves, would need to “ponder these things” in their hearts for a long time, indeed, for a lifetime. Consider the terms of the angelic announcement: the Saviour is here; he is born “for us”; and it’s happening “this day.” In a world governed by imperial edits or early morning tweets, the grace of God presses through with a power beyond this world’s imagining. It’s not the power of Roman legions or angry bluster, but the power—of what? The power of a baby utterly dependent upon his parents; the power of a child’s tender flesh; the power of total vulnerability. For behind this birth is the power of divine love: a self-emptying love that takes flesh and is born in this world; a love of crucifying availability that will finally lead to death; a love that will raise this mangled body and begin a new creation. Today is born for us this Savior.

The announcing angel proclaims this first word of gospel and there is an immediate reaction: not on earth, but in heaven. Celestial beings—a “multitude of the heavenly host”—burst into praise: “Glory to God in the highest heaven.” Doxology, spontaneous joy for the glory of God, fills the heavens and pours upon the earth: “and on earth, peace among those whom he favours.” Tonight we are caught up in the angels’ song. We can catch their ecstatic joy even more, because it is not for angels but for us that this saviour is born. The hardships of this world do not, of course, go away. Mary and Joseph are still dislocated, still pushed around, by forces outside their control, just as their son will experience much later in the story. But that is why he has come: to release us from the self-defeating diminishments human beings are ever devising, to free us from the crushing weight and distortion of sin; and finally to liberate us from death itself. So it is right to praise God tonight, letting the joy of the angels and the peace of heaven surround and envelop us.

Today he is born for us: today. One thing I have learned from my granddaughter is that for very young children, as for animals, it is always today. If we tell her, “Tomorrow we will do such-and-such,” she will ask us, maybe later that day, maybe a few days later, “Is it tomorrow now?” Time simply stops in the apprehension of the present moment. This experience of humans at an early stage of development is perhaps a glimpse of the wondrous eternity of God that becomes present to us in liturgy, in prayer, in fleeting moments of grace, catching us by surprise. It is the “today” when the scriptures, pondered in our hearts, leap into the present.

The Word of God seeks a place to be born. “The Word of God, who is God,” wrote St. Maximus the Confessor in the seventh century, “wills always and in all things to work the mystery of his embodiment.” The Word of God, who is God, thus seeks to be born in us. We take him in, in his scriptural word and in this sacrament, we let him be born—through labour, though self-giving love, through the same vulnerability as this Child we adore. “Be born in us today,” wrote Phillips Brooks in his famous hymn, “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” This day he is born for us. Tonight and every today may he be born in us, making us true children of God.

Thoughts on the Fourth Sunday of Advent, 2017: the text of a sermon preached at the Convent of St Mary, Sewanee

For the Psalm: The Magnificat. For the Gospel: Luke 1:26-38

Our readings on this last Sunday of Advent take us to two points in Saint Luke’s story of Our Lord’s birth. The gospel tells us of the Annunciation, culminating with Our Lady’s joyful acceptance of God’s call, “Be it unto me according to thy word”—and I emphasize that it is joyful. That is particularly clear in Luke’s Greek: clear in a way which is not so evident in English or even in Jerome’s Latin. For Luke’s Mary utters her “let it be” to the angel with a verb that is in the optative mood—γένοιτό μοι. What is the optative mood? We have no equivalent in English. I used to describe it to my students as the “optimistic” mood. The Oxford English Dictionary has “optative” as “expressing wish or desire…characterized by desire or choice”. In other words, what Mary is saying to the angel is not merely, “Yes, all right then, if you insist, I suppose I can live with that,” but “Yes, please, that is what I want!” That, of course, is one reason why the church has long seen her as the model disciple. She does not merely accept God’s will through gritted teeth (which is generally the best I can do, and often not even that) but she actually desires and enjoys God’s will, as one who cannot imagine desiring or enjoying anything else. A very few saints—Saint Francis for example—seem to have come somewhere near that. For me, certainly, and for many of us, I suspect, it is a hope for heaven.

What then of the hymn Magnificat, with which in these last two Sundays in Advent we have replaced our usual psalm? This is Luke’s portrait of Mary’s further rejoicing and reflecting on the angel’s promise. Magnificat has the form of a Hebrew hymn of praise to God, and it has many biblical antecedents. The first part of it is closely tied to Mary’s own situation: she is the one who has been looked upon with favour by God: “he has regarded the lowliness of his handmaiden.” The Hebrew prophets, however, also used the past tense to speak of things that were in fact still to come. Such was their trust that God would do what God had promised! And Mary does this too. “He that is Mighty has done great things for me, and holy is His Name.” Of course the evangelist writing this, and we hearing or reciting it twenty centuries later, have an advantage over Mary, since we live after Our Lord’s life, death, resurrection and the grace of God given us in the gospel. Yet even for us the tension between prophetic hope and experienced reality remains, and especially in the second part of her hymn when Mary moves from her personal experience of God’s grace to her, the woman of low estate, to God’s dealing with society and the world at large. For the fact is, we do not see the rich cast down from their positions of power, we do not see the poor and humble exalted, or the hungry filled with good things. Still less do we see the rich sent away empty. Rather, we seem at times to be living in a kleptocracy, where the rich become obscenely ever richer and the poor are threatened with the loss of even what they have.

And yet, with Mary, we continue to pray Magnificat, in faith that the fulfilment of God’s Word and promise is certain, and that it has already begun. It began in the birth of a baby to a girl whom nobody in the world of her time would have regarded as of the slightest importance, and yet all future generations were to call her blessed. And it begins in the creation of a just society in which power is used in the service of compassion—a society of which we see glimpses and glimmers here and there, but which does not yet, alas, exist.

One thing more should be said. Between Mary’s joyful acceptance of God’s will for her, “So be it!”, and her prayer and prophecy Magnificat there is in Luke’s account a word to her that so far we have not mentioned. It is the word of her cousin Elizabeth. “Blessed are you who believed!” says Elizabeth (Luke 1:45). Mary’s glory is not her position in society, nor her lack of it, nor even her physical relationship to the Messiah, but her faith. And that faith we may share, when we dare to pray with her, Magnificat. An age such as ours—an age when so much that we thought achieved seems to be being undone, so much that we thought secure is being ruined—

Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold.

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity—[1]

such an age surely needs that Advent faith of Mary as St Luke portrays it, a confident assurance that God will fulfill God’s promises and a willingness to work for it.

In fellowship with Mary let us then let us then confess that faith, as the Church has taught us…

We believe in One God….

[1] W. B. Yeats, The Second Coming (1920): written in 1919 in the aftermath of World War I.

Thoughts on a First Profession: the text (more or less) of a sermon preached in the Chapel of the Convent of St Mary on the occasion of the First Profession of Sister Hannah, CSM.

Advent 3, Year B: Old Testament Isaiah 61:1-4, 8-11, Gospel John 1:6-8, 19-28

I spent a very interesting hour last Tuesday talking with Rebecca Wright[1] about this morning’s Old Testament reading—the reading from Isaiah. She thinks that what the prophet may be talking about when he speaks of “the Year of the Lord’s favour” is what is elsewhere called a “Year of Jubilee”.

What’s a Year of Jubilee?

The idea, according to Leviticus 25, was that every fiftieth year in the land of Israel all land would be returned to its original owners, all slaves and prisoners would be freed, all debts would be forgiven and the mercies of God would be particularly manifest. There were, of course, many complications involved in such a project. And some, I gather, doubt whether it was ever really more than an aspiration. But whether it was ever actually attempted or not, it was surely rather a wonderful vision—a vision of a society in which however big a mess you got yourself into, there was always a prospect of forgiveness—forgiveness of debts, forgiveness of the loss of land; a society where by definition there could never be a landless class—a class, in other words, that had fallen through the cracks, that had no stake in or possibility of sharing in whatever prosperity the nation had as a whole. It was a vision of a society that functioned, or at least attempted to function, in accord with the boundless mercy and justice of God.

Our prophet in this morning’s reading sees the return to Israel of those who had been forced into exile and captivity at the Fall of Jerusalem in 597 as such a moment of grace, a time of Jubilee, when what had been lost through the nation’s folly, sin or mere tragedy, would be restored. So he says:

The spirit of the Lord God is upon me,

because the Lord has anointed me;

he has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed,

to bind up the broken-hearted,

to proclaim liberty to the captives,

and release to the prisoners;

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.

According to St Luke, centuries later Our Lord himself was called on to read these very words for the haftorah—that is, the reading from the Prophets—in a service in the synagogue at Nazareth. And he saw in them a vision that also described his own ministry. “Today,” he said when he had finished reading, “this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:21). Here, he told them, in his presence among them, was the true jubilee, the time of God’s forgiveness, the true year of Grace.

All of which brings us to our gospel passage, and the words and deeds of the John the Baptist. As we heard, various people who have been sent by the authorities in Jerusalem want to know what he is up to. After dismissing various suggestions he finally says, “I am a voice”—that is how we might literally translate the Greek—“a voice of one crying in the wilderness, make straight the way of the LORD!” He too, as he goes on to point out, is alluding to the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, although to a different part from the passage we just heard for our first reading. He is alluding to Isaiah 40, verse 3, where Isaiah speaks of, “a voice calling (קוֹל קוֹרֵא)”. But this passage also, like the one we just heard, speaks of the end of Israel’s captivity,[2] and has wonderful words of hope:

Comfort, comfort my people, says your God.

Speak comfortably to Jerusalem,and cry to her that her warfare is accomplished,

that her iniquity is pardoned,

that she has received of the LORD’s hand double for all her sins.

The prophet’s word of summons, “Comfort, comfort (נַחֲמוּ נַחֲמוּ)”—he says it twice, for the matter is urgent!—implies not merely “comfort” in our modern sense of that word, but also challenge, a call to action.[3] So it leads on to “make straight (יַשְּׁרוּ)”! Don’t sit around moping and moaning saying, “We have sinned, our lives are ruined, all is lost”, for the LORD has put away your sin and you have things to do! Rouse yourself! Start living as people who have received forgiveness, a fresh start, and who hope for something even more glorious to come—an eternal destiny as daughters and sons of the living God!

And that, of course, is what this season of Advent is all about. It is the season that looks back to what has been achieved already in the first coming of Jesus Christ, and also forward to the glorious “not yet” promised us in Christ’s second and final coming. So I agree heartily with what Fr. Rob said to us on Advent 1. Advent is not merely a passage to be got through between Thanksgiving and Christmas, a path by way of too much Christmas shopping from one turkey dinner to the next (though to be sure, as an English traditionalist I eat goose at Christmas). No. Advent is actually the season that speaks most directly and plainly to where we really are now. “You were saved in hope,” is the way St Paul puts it (Rom. 8:24), and much of the rest of his correspondence says in effect, “so act like it!” Act as if you really were expecting “a new heavens and a new earth,” as 2 Peter puts it, “the abode of justice” (3:13).

And so we come to this particular morning in this particular place, where a courageous young woman does act in this way. She places her hope in God and commits herself to live in personal poverty—poverty of spirit and simplicity of life; to celibacy; and to a life of obedience, praying that her will may be in harmony with God’s will. All this she attempts for the sake of God’s kingdom and in fellowship with her sisters, other brave women who long ago made this same commitment, as well as in fellowship with still others who have gone before them through the centuries—Hilda of Whitby, Teresa of Ávila, Constance and her Companions, and thousands more.

My friends, what better witness could we have than this of what it means to be what we are all called to be—Advent people, people who look for the coming grace of God?

I’m a Londoner as you know (to be precise, a cockney and proud of it), and I remember once a little cockney Franciscan being asked what was the point of what we call “the religious life”. What did he, as a Franciscan monk, actually do? Since his was a life of service, he could have named many things that he did, but what he actually chose was this.

“Look,” he said, “you know everyone’s supposed to say their prayers, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Well they don’t always do it, do they?”

“Er—no. I suppose not.”

“Well then, we says ’em for ’em!”

Sister Hannah and her sisters will certainly receive personal gifts of spiritual enrichment through their commitment to the religious life, as do we all for our attempts at faith, love and obedience. But that’s just a side effect. The Sisters and their fellow religious throughout the world don’t actually do what they do for their own enrichment at all. They do what they do for God’s kingdom and for us, for the sake of the world, which God loved so much that he gave His Only Begotten Son to die for it.

So let us, people of the Advent in this third Sunday of Advent, rejoice in our fellowship with these gallant ladies and today especially with Sister Hannah, as they bear their witness to us and for us. Let us pray for grace ourselves to bear that witness with them, in our own way and according to our own calling. And let us now and always joyfully confess the faith that we all share, as the church has taught us.

We believe in One God…

[1] The Reverend Dr Rebecca Abts Wright, C. K. Benedict Professor of Old Testament and Biblical Hebrew at The School of Theology of The University of the South in Sewanee.

[2] While the Book of Isaiah as a whole is surely marked by a distinct theological and even to some extent literary unity, it remains that there are also within it distinctions of tone and apparent situation that persuade many (me among them) that it actually contains the work of three prophets over a considerable period of time. Simplifying considerably, one may reasonably speak of an eighth century “First Isaiah”, who lived and prophesied in Jerusalem before the exile and was largely responsible for our Isaiah 1-39; a “Second Isaiah” (or “Isaiah of Babylon”) who lived in Babylon near the end of the exile and was responsible for Isaiah 40-55; and a “Third Isaiah” who was in Jerusalem at a time when, following Cyrus’ edict of 538 (see Ezra 5.13-15, 6:3-12), the exiles were able to return, and whose prophesies are largely reflected in Isaiah 56-66. In view of the connections between them, it is quite possible that Second Isaiah was Third Isaiah’s master and teacher (see e.g. Claus Westermann, Isaiah 40-66, D. M. G. Stalker, transl. [London: SCM 1969 (1966)] 366). According to this view our first reading this morning is from Third Isaiah, but the Baptist in our gospel passage is alluding to Second Isaiah. All that granted, of course neither John the Baptist nor the Evangelist knew any of it, and I doubt they would have cared if they had. The important point for their purpose, and as it happens for mine too, was that they all were talking about God’s forgiveness, God’s grace, God’s Jubilee, which they believed themselves called on to proclaim.

[3] This was original sense of English “comfort” (from Latin confortare: con intensive + fortis) which carried meanings such as, “to strengthen; to encourage; to support; to invigorate” as late as 1674 (see OED “Comfort v.”). So in 1611 when King James’ translators chose it, it was an excellent translation of the Hebrew נַחֲמוּ. Thus, one may note, the “comfortable words” in the Eucharistic Rite of various versions of The Book of Common Prayer (beginning with 1549) are clearly intended to invigorate God’s people, not merely to give them a consoling pat on the head!

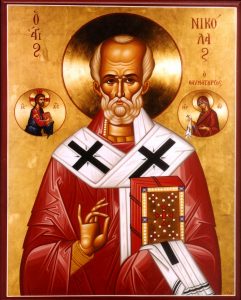

Saint Nicholas of Myra: text of a sermon preached by Robert MacSwain in the Chapel of the Apostles on the 6th December 2017

For the Proper: Proverbs 19:17, 20-23, Psalm 145:8-13, 1 John 4:7-14, Mark 10:13-16

For the Proper: Proverbs 19:17, 20-23, Psalm 145:8-13, 1 John 4:7-14, Mark 10:13-16

You disgust me. How can you live with yourself?

You sit on a throne of lies.

You’re a fake.

You stink. You smell like beef and cheese.

You don’t smell like Santa.

Yes, the classic “You Sit on a Throne of Lies” scene from the great 2003 film Elf, starring Will Farrell as Buddy, the human being who grew up at the North Pole believing himself to be one of Santa’s elves—despite the fact that he’s twice as big as everyone else.

In this famous scene he unmasks—or rather un-beards—a department store Santa as an imposter, not the real Santa Claus at all, whom Buddy of course knows personally. But while Buddy’s righteous anger at the hapless impersonator is certainly amusing, to me this scene is not quite as funny as Buddy’s unfortunate later encounter with a very pre-Game of Thrones Peter Dinklage as a children’s book author whom Buddy innocently calls an “angry elf” with calamitous results.

Now, if Dr King were preaching on St Nicholas of Myra, I’m sure he would tell us all about the actual history of this fourth-century bishop who was born in modern-day Turkey, persecuted under Emperor Diocletian, attended the Council of Nicaea (where according to tradition he was so angry at Arius that he slapped him), who was famous for his pastoral concern for the poor and vulnerable, whose generosity gave rise to many pious stories and legends, and who later became the patron saint of children, students, sailors, brewers…among other occupations…as well as various cities and countries. St Nicholas actually made the news earlier this year when archeologists announced that they may have found his intact tomb in Myra, where he was bishop, rather than Bari in Italy where it was long thought his relics had been taken. But wherever his remains lie, Nicholas died on December the 6th in 343, so today marks the one thousand six hundred and seventy-fourth anniversary of his death.

St Nicholas is often valorized as someone who combined a firm commitment to economic justice with a rigorous doctrinal orthodoxy. Hence our texts from Proverbs—“Whoever is kind to the poor lends to the LORD” (a remarkable thought!)—and the First Letter of John, which explains how the eternal love of God became incarnate in Jesus (paradigmatically, the first Christmas present): “God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him.”

So there is indeed much of value to be said about Nicholas. But as a mere theologian rather than a church historian, my primary interest this morning is focused less on the historical St Nicholas of Myra as on the figure he later became, namely Santa Claus. And, in particular, the way in which in popular culture the disputed existence of Santa Claus is often used—more or less obviously—as a proxy for debates about the existence of God.

This sotto voce association between God and Santa goes back at least to 1897, with Francis Pharcellus Church’s famous editorial, originally titled “Is There a Santa Claus?”, responding to a letter from eight year-old Virginia O’Hanlon. Virginia wrote that some of her “little friends” disbelieved in Santa and thus asked the newspaper editor if he was real. The first two paragraphs of Church’s response go like this:

Virginia, your little friends are wrong. They have been affected by the skepticism of a skeptical age. They do not believe except they see. They think that nothing can be which is not comprehensible by their little minds. All minds, Virginia, whether they be men’s or children’s, are little. In this great universe of ours man is a mere insect, an ant, in his intellect, as compared with the boundless world about him, as measured by the intelligence capable of grasping the whole of truth and knowledge.

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! how dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus. It would be as dreary as if there were no Virginias. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence. We should have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished.

Now the great irony here is that Church himself was a skeptic and atheist, but when confronted with a question from an eight year-old he could not bring himself to speak what he regarded as the real truth to poor little Virginia: namely that there is no Santa, we’re all going to die, and life is ultimately meaningless. And thus despite his personal cynicism Church wrote what has become, according to the Newseum in Washington, DC, “history’s most reprinted newspaper editorial, appearing in part or whole in dozens of languages in books, movies, and other editorials, and on posters and stamps.”

Although it is never cited directly, basically the same perspective as Church’s editorial forms the basis of the classic 1947 film Miracle on 34th Street, in which a man calling himself Kris Kringle and claiming to the one true Santa Claus meets a divorcée named Doris (played by Maureen O’Hara) and her daughter Susan (played by a young Natalie Wood). Early in the film, Doris’s love-interest Fred is shocked to discover that Doris is raising Susan to be completely rationalistic in her approach to life. So Fred asks Doris, “No Santa Claus, no fairy tales, no fantasies of any kind. Is that it?” And Doris replies, rather briskly: “That’s right. I think we should be realistic and completely truthful with our children, and not have them growing up believing in a lot of legends and myths, like Santa Claus for example.”

Doris is thus deeply distressed to discover that Mr. Kringle, the kindly old man who looks just like Santa Claus, thinks he really is Santa Claus. Her only conclusion is that he must be crazy—so he is institutionalized in a mental hospital. Fred, a lawyer, takes it upon himself to get him out, which means proving in court that Mr. Kringle is not crazy after all. When Doris and Fred have a big argument about all this, Fred echoes Church’s editorial: “Faith [he says] is believing in things when common sense tells you not to….[Things like] Kindness and joy and love and all the other intangibles” that make life meaningful.

My third and final example is the film I began with, Elf. We are told at the start of the movie that Santa’s whole mission of toy delivery is in grave danger. Santa’s sleigh flies on “Christmas spirit” (let the reader understand) and when “Christmas spirit” runs out due to general cynicism and skepticism, the sleigh is grounded. Each year fewer and fewer people believe in Santa, which has created a serious energy crisis. But if enough people do believe in Santa, the sleigh will fly and presents will be delivered. However, such belief cannot be based on empirical evidence: as Santa says to a little boy in the film, “Christmas spirit is about believing, not seeing. If the whole world saw me all would be lost.”

Now my point here is the simple observation that in Church’s editorial, in the debates between Fred and Doris in Miracle on 34th Street, and in the lack of “Christmas spirit” in Elf, the real topic being discussed, if only subliminally, is not in fact Santa Claus but God. It is God who has been placed in the mental asylum of our intellectual culture, God whose sanity must be questioned within the court of common sense, God whose existence must be justified—if at all—not through hardheaded reason and empirical observation but through…what? What precisely is the operative epistemology at work here in Church’s editorial and these films?

Well, at best it seems to be simple unquestioning faith, but at worst it seems to be merely pragmatic sentimentality and nostalgia for the naivety of childhood. We live in a dry and disenchanted age: our culture has fallen away from genuine religious belief, but we’re still worried enough about our skepticism that the question keeps emerging in rhetoric about “Christmas spirit”: apparently belief in God is like belief in Santa Claus—both are equally crazy or unfounded, but well…who cares? We’ll never know anyway. So pass the eggnog and keep the season bright.

At this point in my sermon I turn somewhat desperately to the thus-far-neglected gospel lesson,

When what to my wondering eyes should be seen

But Mark, Chapter ten, beginning with verse thirteen:

People were bringing little children to Jesus in order that he might touch them; and the disciples spoke sternly to them. But when Jesus saw this, he was indignant and said to them, “Let the little children come to me; do not stop them; for it is to such as these that the kingdom of God belongs. Truly I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will never enter it.” And he took them up in his arms, laid his hands on them, and blessed them.

Well, by St. Nicholas, I have to admit that this is not quite the operative epistemology that I was hoping for. Doesn’t all this “receive the kingdom of God as a little child” business play right into the hands of the sentimental cynicism that I’ve been tracking since 1897? Or is all that stuff sentimental cynicism after all? I mean, what’s the difference between Santa’s response to the boy in Elf—“Christmas spirit is about believing, not seeing”—and Jesus’ response to Thomas, “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe”?

We need to tread carefully here, because what might not be good reasons to believe in “Christmas spirit” might actually be good reasons to believe in God or the resurrected Christ. Whether or not it is rational to believe something depends partly on the object of belief and not just on the offered reasons. These are dark and difficult matters. But there is an important difference between, say, Church’s editorial and Mark’s gospel, on how they view the crucial perspective of children.

The world to which Jesus belonged did not value childhood as such, which is why the disciples tried to discourage the parents from bringing their children to Jesus, and so in his words and actions Jesus offers a profound transformation of values: there is something, he says, essential to the character of a child that is necessary for those who would belong to the kingdom of God. So what is it?

I suggest that the childlike character Jesus endorses here is being open and receptive to the Word of God and the Gospel of Christ. The technical term for this in Catholic theology is docility: according to Thomas Aquinas, docility is part of prudence, and is a moral and intellectual virtue necessary for us to learn anything new from a parent or teacher: children and students without docility cannot learn and grow in knowledge. Jesus is not telling us to be child-ish, but he is telling us to be child-like, docile, “for it is to such as these that the kingdom of God belongs.”

By contrast, 1800 years later, Francis Church has a wildly exaggerated view of the importance of childhood: without the innocence of Virginia and her little friends, he says, “The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished.” But now childhood itself, rather than Christ, has become the light of the world. And yet in making this claim Church is himself in bad faith: he doesn’t believe what he is telling Virginia, and in fact when the editorial was originally published he refused to print his name with it so it appeared anonymously.

We are called to be a different Church than Church. The light we proclaim is not the light of childhood but the light of Christ. The Spirit we proclaim is not the “Christmas spirit” but the Holy Spirit, for by this “we know that we abide in him and he in us, because he has given us of his Spirit.” And we prove ourselves to be true venerators of St Nicholas of Myra by our compassionate generosity to the poor and vulnerable, the weak and the oppressed, those without voice or agency.

But maybe, just maybe, instead of slapping heretics, tempting as that might be, perhaps we should instead follow Buddy’s friendlier example, reach out our arms and ask them: “Does someone need a hug?” (But remember: if they say no then leave them alone!)