Month: April 2017

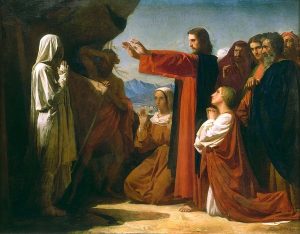

Thoughts for the Fifth Sunday in Lent: The Raising of Lazarus

Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat (1833-1922)

It’s appropriate that on this last Sunday before Palm Sunday and Holy Week we hear the story of what Saint John presents as the last mighty act of Jesus’ ministry—a mighty act that, according to the evangelist, not only glorifies the Father and leads many to believe in him, but also leads directly to the authorities deciding that he must die.

Let’s look a little more closely. First, we note that the sisters’ message to Jesus is modest. Obviously, it isn’t sent without the hope that he may do something, but it asks nothing, and it certainly doesn’t suggest what he ought to do. It simply lays the situation before him: “Lord, he whom you love is ill.” We’re reminded of his mother’s words to him at the beginning of the gospel, at the marriage at Cana, “They have no wine,” she says. Of course we may be sure that she, too, has her hopes. But she certainly doesn’t suggest to Jesus what he should do.

As with Mary at Cana, so here, Our Lord’s initial response seems disappointing. He says that what’s happening “is for God’s glory” and then stays “two days longer in the place where he was.” Why does he do this? The evangelist soon tells us: Lazarus has already died—presumably almost directly after the sisters sent their message—and Our Lord knows this: “Lazarus is dead,” he says to the disciples, in case there’s any doubt in their minds. (Although the evangelist doesn’t tell us how he knows it, I’m not sure that the suggestion made by some scholars that he’s learned it “supernaturally” is really necessary.[1]) Anyway, with the two days that Our Lord remains where he is, and then the two days that it takes him and the disciples to travel to Bethany, it means, as the Evangelist carefully points out, that when he arrives, “Lazarus had already been in the tomb for four days.” Perhaps a point is being made: some rabbinic tradition said that the soul might hover near the body for three days, but after that there was no hope of revival or resuscitation.[2] In other words, it’s very clear that Lazarus is really dead.

Before Jesus even arrives at Bethany, first Martha, and then Mary, come to meet him. The way in which they are portrayed here somewhat reflects the way they are portrayed in Luke’s gospel. Martha is the busy one who gets there first and then organizes her sister Mary to go. Mary is the one who simply falls at his feet. Yet both make the same affirmation: “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.”

To Martha he gives a response that is at once a statement of his identity, and a promise: “I am the resurrection and the life.” How right our Prayer Books have been always to place this text as the beginning of our burial liturgy! For this—the resurrection and the life—is what Jesus always is in relation to us. He is the resurrection in that if we put our trust in Him (as indeed Martha has done) though we indeed come, as do all, to the grave, yet we shall live: we shall not die eternally. And he is “life” because all who receive the life that he gives can never really die: because the life that comes to us through our relationship with Jesus is already eternal life—as He says later in his high-priestly prayer: “This is life eternal, to know thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom thou has sent.”[3] That’s our Lord’s response to Martha.

His response to Mary is to weep with her. “Jesus wept.” It is, I’ve been told, the most quoted verse in the New Testament. I don’t know. Perhaps it is. And if so, perhaps for good reason. God knows, there is more than enough to weep over in our world! So how important to remember that Our Lord weeps with us! That at the heart of God’s divinity there is sorrow for our sorrow! That, as the old hymn had it, “There is no place where earth’s sorrows are more felt that than up in heaven.” “In all their afflictions,” the prophet Isaiah said of Israel’s history, “God was afflicted.” And our Lord himself has told us, “not a sparrow falls to earth, but God knows”—and God cares. Surely it does not do away our sorrows to know that our Lord weeps with us. But it helps.

But our Lord does not only weep. He goes to the tomb with Mary and Martha, and there performs a mighty act. “Come forth,” he says, and Lazarus comes. “Unbind him,” he says, “and let him go.” And so Martha and Mary see the glory of God, just as our Lord had promised them.

The story is told without fuss or elaboration—and we feel its power still, 2000 years after it was written. It is, as we began by saying, appropriate that before we move to contemplate the Passion of our Lord, we hear of this mighty act. It’s appropriate for two reasons. First because, at least in John’s view, what Jesus did here was a major factor in leading the authorities to decide that he must die. And second, because it is a fitting prelude to the miracle of Easter itself, the resurrection of our Lord. Of course it’s not a story of resurrection in the Easter sense. Our Lord rises, as Saint Paul reminds us, never to die again. Death has no more dominion over him. The story of Lazarus being raised is not a story like that. Lazarus after being raised is still subject to this world of sin and death, and will die again. But, like other stories of God’s servants raising the dead in Scripture, it is a story reminding us that our God is not bound by death, indeed that our God is sovereign over death. The Lord who raised Lazarus is the one whose own resurrection will be the gateway for us to everlasting life. The raising of Lazarus is a sign and pledge guaranteeing his power to fulfill his promise to Martha: “Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die.”

[1] Barrett, John (revised ed.) 391.

[2] Eccl. R. 12.6; Lev. R. 18.1; cf. G. Dalman, Jesus-Jeshua [ET 1929] 220.

[3] John 17:3